Robert De Niro and Al Pacino, undeniably two of the finest actors of their generation, finally got to share the screen together over a coffee in Michael Mann’s 1995 film Heat. The former played professional thief Neil McCauley, the latter a police officer named Lt. Vincent Hanna who had spent years on McCauley’s tail. “Don't let yourself get attached to anything you are not willing to walk out on in 30 seconds flat if you feel the heat around the corner,” McCauley says in the film’s most memorable line.

It was the moment cinephiles had been waiting for since the actors had appeared (separately) in The Godfather Part II in 1974. But for those who’d watched a certain TV movie six years previously, their conversation may have sparked a sense of déjà vu.

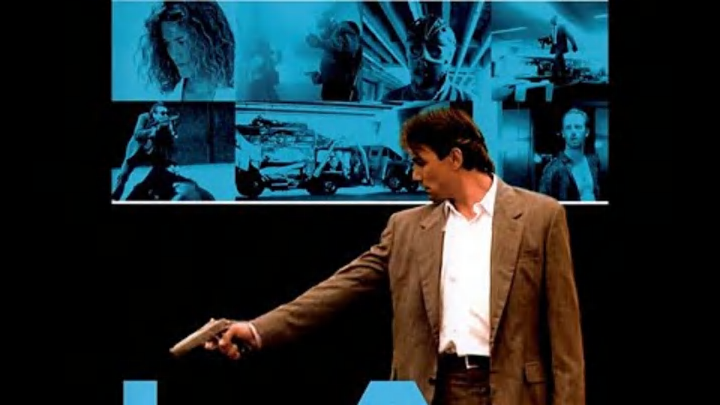

The greatest scene from what many consider to be the greatest ‘90s film (despite its remarkable snubbing at the Academy Awards) was copied almost verbatim from 1989’s LA Takedown. This wasn’t an open-and-shut case of cultural theft, though: The forgotten NBC picture was also Mann’s brainchild, one that he skillfully remodeled into an engrossing big screen crime saga worthy of its A-list talent.

From TV Pilot to TV Movie

Mann had actually started working on the idea before his directorial debut, Thief, hit theaters in 1981 (interestingly, he initially wanted friend Walter Hill to direct it, but Hill said no). It was based on a real-life ’60s manhunt involving former Chicago cop Chuck Adamson and prolific robber Neil McCauley—including the coincidental moment they bumped into each other on the street. “I didn’t know what to do: arrest him, shoot him or have a cup of coffee,” Adamson reportedly once said. At that time, they chose coffee, but Adamson would fatally shoot McCauley a year later following an attempted heist at a supermarket.

Mann continued to hone the screenplay throughout the following decade, and as his slightly more pastel-colored TV crime drama Miami Vice was nearing the end of its five-season run, its home network decided to commission the idea as a potential show. To make LA Takedown (known at that point as Hanna) work for a TV pilot, Mann took his original script and trimmed it by more than 100 pages. But after some creative disputes with NBC president Brandon Tartikoff—including the choice of leading man—its pilot episode wasn’t deemed worthy of a pick-up to full series. (Mann would later scratch his police procedural itch as executive producer of CBS’s one-season wonder Robbery Homicide Division.)

LA Takedown did eventually surface as a 97-minute television movie, with Alex McArthur and Scott Plank taking on the roles of the hunted Patrick McLaren and the hunter Lieutenant Vincent Hanna, respectively. Plank (and several other cast members) had also appeared on Miami Vice, while Michael Rooker, who played second-in-command Bosko, had worked with Mann on his other, grittier cop show, Crime Story. (Only one LA Takedown actor, however, made the leap to Heat: Xander Berkeley played gang member Waingro in the TV movie before taking on the role of Justine’s one night stand, Ralph, in the film.)

Reviews were mixed, with the Los Angeles Times describing LA Takedown’s bank shootout scene as “riveting” and praising the chemistry between McArthur and co-star Laura Harrington (who played Eady, his character’s girlfriend). The review also argued—rather presciently, as it happens—that both deserved a “different, better picture.”

Bringing the Heat

That “better picture” arrived in 1995, joining the likes of Alfred Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much, Michael Haneke’s Funny Games, and Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments in the club of directorial do-overs, and 12 Angry Men and Marty on the list of theatrical films adapted from TV movies. LA Takedown has since drawn multiple unfavorable comparisons with Heat, with The New York Times writing that its “themes are bluntly stated, complex relationships are sanded down, and the good guy-bad guy dynamic is vastly simplified.”

LA Takedown (which, despite Mann’s standing as one of Hollywood’s greatest crime storytellers, is currently unavailable to stream) is indeed a conventional, bare-bones watch, far more interested in the cat than the mouse. Heat, meanwhile, allows both protagonists to drive the narrative while cleverly filling in more of the gaps, reinstating subplots such as Robert Van Zant’s (William Fichtner) double-crossing antics, Chris’s (Val Kilmer) gambling problems, and the suicidal tendencies of Hanna’s stepdaughter Lauren (a young Natalie Portman).

Its ending is also less satisfactory: McLaren meets his maker not at the hands of his law-enforcing nemesis, but his volatile partner-in-crime Waingro. Heat, on the other hand, sticks closer to real-life events by having McCauley be gunned down by Hanna (albeit on an airport runway rather than in the wake of a supermarket shootout).

Of course, contrasting like for like could be considered a little unfair. LA Takedown had a considerably lower budget and just a 19-day shoot. Following his Oscar-winning success with Last of the Mohicans, Mann was given $60 million and nearly four months to make Heat. LA Takedown was bound by the constraints of network television, and because it was only intended to be a taster of a full series, it had 73 minutes less to tell its story.

And there’s one way in which LA Takedown could never compare: It’s the frisson of knowing that De Niro and Pacino are about to butt heads for the first time that makes Heat so compelling. Several decades younger, and without the shared history, poor Plank and McArthur were never going to be able to compete. “Like comparing freeze-dried coffee with Jamaican Blue Mountain,” Mann later explained about the two experiences. “It’s a completely different kind of undertaking.”

As he also acknowledged, LA Takedown gave Mann the stuff of filmmakers’ dreams: a trial run that provided invaluable lessons for the real thing. “I charted the film out like a [two-hour, 45-minute] piece of music,” the director once said about how he restructured the original story. “So, I’d know where to be smooth, where not to be smooth, where to be staccato, where to use a pulse like a heartbeat.” Without the opportunity to iron out the script’s problems, the long-awaited coming together of two Hollywood titans is unlikely to have created such a sizzle.

Read More About Movies: