The response from her publisher was not promising. Mary Renault, the author of four modestly successful novels with Longmans, Green & Co., had turned in the manuscript of her fifth and most daring book yet in autumn 1952. It was a striking departure from her earlier romances between doctors and nurses. It would be, as David Sweetman writes in Mary Renault: A Biography, “the first openly [gay] novel by a serious writer to be published in Britain” since World War II.

Longmans believed readers who ran out to buy Renault’s new book, expecting another heterosexual melodrama, “would be in for a shock,” Sweetman writes. The publisher may have been right to worry. Sexual acts between men were still illegal in Britain. Laws dating back to the 1850s held that books likely to “deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences” were obscene and could be destroyed. That’s what had happened to Radclyffe Hall’s lesbian novel The Well of Loneliness, which was banned from publication for years. William Morrow and Company, Renault’s U.S. publisher, refused to release her book.

Despite their misgivings, The Charioteer would launch Renault’s career as a bestselling writer boldly exploring gay themes with gay readers in mind—in an era when police entrapment of gay men was roiling Britain, the “lavender scare” purged gay workers from U.S. government jobs, and LGBTQ readers longed for reflections of themselves.

An Adventure at Oxford

Born Eileen Mary Challans in 1905, in what is now East London, Renault’s early life was marked by her parents’ unhappy union and their obvious preference for her younger sister, Joyce. Her father, a physician, ignored her and dismissed her ambitions; Mary’s mother nagged her incessantly.

With some relief, Renault was sent to a girls’ boarding school in Bristol, where she developed an obsession with the theater and went to see plays as often as she could. She also got lost in classical Greek philosophy and mythology. “We had a rather good library at my school because, I think, somebody had given them a whole lot of books which we weren’t actually taught at all,” Renault recalled years later, according to Sweetman. “I found Plato’s Dialogues and I was entranced by them. By the time I left school I had read all of Plato, in translation, on my own.”

Around 1924, Renault began attending Oxford University’s St. Hugh’s College, a women’s school whose faculty was only just recovering from an internal implosion. The squabble originated with the college’s principal, Charlotte Moberly, and and her second-in-command, Eleanor Jourdain. During a trip to Paris in 1901, the two women had visited Versailles. Moberly claimed to have seen a vision of Marie Antoinette on a bench in the garden, along with others in 18th-century garb. She discussed the experience with Jourdain, who had witnessed a similar scene, and came to believe they had somehow stepped into a time portal to 1792. They published their story as An Adventure in 1911, giving St. Hugh's an eccentric reputation.

Renault, no doubt used to drama, made the most of her time there. She viewed antiquities in Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum, wrote medieval-themed poetry, and composed and acted in the college’s plays. Despite her love of history and writing, she graduated without a clear direction.

Nursing Her Novels

When her father forbid her from getting a job to support herself, Renault moved back in with her family and tried to continue her writing. She was lonely and cut off from her college friends, and the words failed to flow. She realized she needed life experience from which to draw her characters and their stories, and it dawned on her that, at age 28, she had seen very little of the world and the people in it. In 1933, on a long walk through the Cotswolds, Renault hiked into Oxford for the first time in five years. She passed by the Radcliffe Infirmary, a nursing school near the St. Hugh’s campus. She walked in and told the matron she wanted to become a nurse.

Renault found the work physically exhausting and dominated by silly Victorian-era regulations, but it allowed her to observe the microcosm of patients, nurses, doctors, and administrators around her and file away her impressions. A colleague, knowing her love of the theater, introduced her to another trainee named Julie Mullard who had similar interests. Mullard was a year or two ahead of Renault in school, but about eight years younger. Their paths rarely crossed except after hours at university-sanctioned activities, though Mullard tried to invent opportunities to run into Renault. Around Christmas, it was traditional for Mullard’s residence hall to throw a party, and she nervously invited her crush. Renault ended up spending the night.

Upon Renault’s graduation in 1936, they both worked as nurses at a string of infirmaries, boarding schools, and hospitals. Sometimes they were hired in different cities, making it difficult to grow anything like a healthy relationship. On top of everything, they had to keep it a secret from their employers and landlords.

Somehow, Renault channeled her nursing experiences into novel form. At night, or when Mullard was at work, she penned Purposes of Love, a novel set in a hospital not unlike the ones in which she toiled. The plot followed the heterosexual romance of nurse Vivian and pathologist Mic, but also introduced storylines around Mic’s unrequited crush on Vivian’s brother and Vivian’s intrigue with a lesbian colleague.

Purposes of Love (1939) wasn’t the first British novel to examine the fluidity of sexuality—Alex Waugh’s The Loom of Youth (1917) and The Well of Loneliness (1928) addressed it to varying degrees. And like those earlier books, Purposes of Love earned polarizing reviews. An Observer critic commended Renault’s writerly skill, but other reviewers zeroed in on the characters’ unconventional sexuality. As one wrote in the Sunday Times, included in Sweetman’s biography, “Although we are accustomed to find much in the books of today which would have shocked the Edwardians out of their skins, there are those who still like to think that studies of the sexually abnormal, however ‘slight’ that abnormality may be, should best be confined to the consulting room.” Even some nurses felt the characters’ bisexuality had impugned their profession.

When the novel was published in the U.S. (as Promise of Love), a New York Times critic called it “an unusually excellent first novel.” But attention for Renault’s next published novels, Kind Are Her Answers (1940) and The Friendly Young Ladies (1943), was thwarted by the events of World War II. Renault and Mullard were thrown into the war effort, treating injured soldiers and dodging bombs at a series of military hospitals in London.

Right after V-E Day, however, Renault got to work on her next book. Return to Night, published in 1947, covered similar emotional and professional territory as her earlier novels, but the plot hinted at Plato’s influence on her concept of human nature.

Return to Night unexpectedly won the shockingly lucrative Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Novel Prize, which promised a minimum award of $150,000 and adaptation for a movie. In one stroke, Renault earned the equivalent of $2 million in today’s money, more than a nurse in post-war England could hope to see in her lifetime. (The movie, however, never made it to the screen.)

Renault and Mullard immediately began planning their future without damp, rented flats and prying matrons. They wanted warmth and ease, where Mullard could continue her work as a nurse specializing in brain injuries and Renault could write for a living. They chose Durban, South Africa—then a British colony—mainly because post-war laws restricted how much money could be taken out of the British Empire.

“Could Not Be ... Less Likely to Offend Against Morality”

The change stimulated a new phase in Renault’s writing. In her mind, the strands of her intellectual life—her passion for Greek history and philosophy, her sexual politics, and her artful storytelling—were braiding together. She began what would be her last contemporary novel, The Charioteer, the title a reference to Plato’s description of the soul as a chariot driven by two horses, one of which is “fine and good and of noble stock, and the other opposite in every way.”

The person driving the chariot in Renault’s novel is a soldier named Laurie, who is wounded at Dunkirk and is cared for by Andrew, a conscientious objector volunteering at the hospital. Laurie falls in love with chaste Andrew, but later reconnects with a former crush named Ralph at a gay party, and must choose between the Platonic ideal or imperfect gratification.

The Charioteer struck a chord among gay readers in the UK when Longmans agreed to publish it in 1953. Copies were smuggled into the U.S. and publicized by word of mouth, making it even more of a literary phenomenon. Longmans apparently overcame its fear of prosecution for obscenity: It ran ads touting the novel as “a beautifully written story which presents the male version of the problem raised in The Well of Loneliness.”

A reviewer for the Western Mail, noting that it “could not have been written at any other time than the present, because it deals with the love-relation between men,” praised The Charioteer as “serious, extremely well-written, assured in style and comprehensive in argument, [and which] should be read by all who wish to understand their fellow creatures.” Another advertisement for the book crowed, “steady sales for eight months,” while hastening to quote the Birmingham Post: “Miss Renault’s treatment of the theme of homosexual love could not be more honest, impartial, or sympathetic, or less likely to offend against morality.”

The Charioteer was a huge success, but it marked the conclusion of Renault’s efforts to present ancient philosophical arguments in contemporary settings. Her next novel would flip the script and use real events and figures in Ancient Greece to comment on modern conflicts.

“A Glowing Work of Art”

In 1954, the ruling Nationalist Party in South Africa began enforcing legal racial discrimination across the whole of society, placing all residents into one of three racial categories and stripping most civil rights from Black South Africans. Renault and Mullard, who had certainly enjoyed the privileges of being white and British since moving to Durban, were appalled by apartheid. Renault couldn’t help but associate the breakdown of South Africa’s society with the final events of the Peloponnesian War in the 5th century CE, in which stratified, militaristic Sparta conquered democratic Athens.

In her next book, The Last of the Wine (1956), an Athenian youth named Alexias narrates his coming of age during that tumultuous era. He befriends a slightly older man named Lysis, a pupil of Socrates and confidant of Plato, who becomes his lover and mentor. Then Alexias and Lysis are swept up in the war, their paths diverge, and a former chum from their school days returns to seal their fates.

If Longmans had reservations about publishing Renault’s previous novel, it was even more concerned about her foray into ancient wars and socially sanctioned same-sex relationships. Pantheon agreed to publish The Last of the Wine in the U.S. and rightly highlighted its historical erudition in its publicity campaign, which critics picked up on. “A remarkable novel, vivid and moving,” The New York Times Book Review critic Orville Prescott wrote. “The canvas is rich in battles by land and sea, and the starvation of siege and the disaster of defeat, and in sensitively poised emotional bonds between both man and woman, and man and man. … It is a glowing work of art.”

Prescott also saw Renault’s protest of events in South Africa, but may have been thinking about the scourge of McCarthyism as well: “The parallels between [Alexias’s] age and ours are deadly—wars and loss of liberty, political passions and the terrors of dictatorships, atrocities and retaliations. Miss Renault does not overemphasize these similarities, but they are there and they are disturbing.”

As with The Charioteer, gay readers were hooked on the honesty and openness in The Last of the Wine. According to Sweetman, her mailbox was crammed with letters from gay men who thanked the author for articulating their desires; they shared their memories of intimate friendships with school mates and army buddies. Renault had not just found an adoring audience; she found her unique métier.

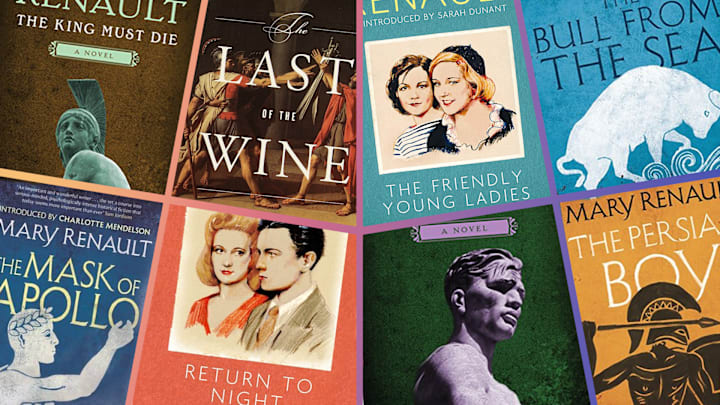

She published seven more successful novels between 1958 and 1981. She followed up The Last of the Wine with The King Must Die (1958) and The Bull From the Sea (1962), a novel and sequel that imagine the Greek hero Theseus’s coming of age and battle with the minotaur of Knossos. By then, “gay bookshops in San Francisco had prominent ‘Renault' sections,” Sweetman writes.

The Mask of Apollo (1966), inspired by a bust of the Olympian god Renault saw on a visit to Greece, examined a political crisis in the city of Syracuse through the eyes of a tragic actor whose conscience takes the form of a golden mask. Her explorations of the life and loves of Alexander the Great—Fire From Heaven (1969) and The Persian Boy (1972), the latter her most gay-themed novel yet—had critics gushing over her realistic details and psychological analysis of the Macedonian king, while her gay audience felt vindicated in her telling of Alexander’s intimate relationships with Hephaestion and Bagoas, the titular youth. The Persian Boy was her fastest bestseller to date.

Following her 1978 book The Praise Singer, Renault returned to Alexander’s story with Funeral Games (1981), which dramatizes the aftermath of the king’s death and the internecine fight among his followers to claim his throne.

Her final novel’s title was too apt. By the time it was published, when Renault was about 75 years old, she had already had one bout with cancer—though Mullard, knowing her abhorrence of lingering illness, didn’t tell her—and a serious fall that had laid her up for months. Now, she found it harder to breathe and get down to her study to write. Doctors diagnosed lung cancer, and again, Mullard kept the secret so Renault could focus on her work.

Renault died in December 1983, just after reading a letter from her friend, the maritime novelist Patrick O’Brien, who told her he’d overheard a man speaking her name at a dinner party. The man’s friend wanted to know whom he should read for insight into Greek history. “‘Oh, Mary Renault every time,’" O’Brien said, repeating what the man had answered. "'Mary Renault—perfect for historical accuracy, perfect for atmosphere.’ I could hardly have put it better myself.”