In a Brooklyn, New York, hospital in May 1941, Beth Allen and her twin sister were born three months prematurely, their chances of survival slim. Most hospitals weren’t yet equipped with the right facilities to care for premature infants, and doctors simply didn’t have the resources or skills they needed to help.

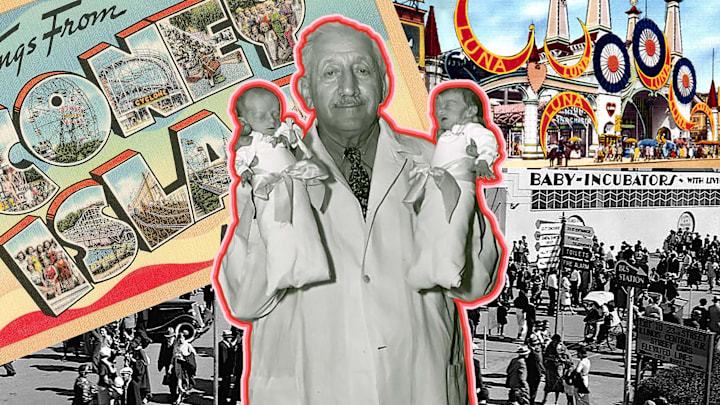

Beth’s sister died after just two days, and the new parents were left with few options to save their only remaining child. Aware that they were working against time, the hospital staff proposed placing Beth under the care of a doctor with a familiar name: Dr. Martin Couney of Coney Island. In addition to providing treatment free of charge, Couney would put Beth—who weighed only one pound, 10 ounces—on display as part of an exhibit on the amusement park boardwalk.

Beth Allen’s parents had heard of Couney’s shows before. Couney and his staff of nurses would give Beth the medical help she needed, in a tent or enclosed area. As she lay in a life-saving incubator, visitors could pay an admission fee to look at her from behind the machine’s glass window.

Couney had started holding baby incubator shows around the turn of the 20th century. Incubators were somewhat rare at the time, and while Couney didn’t invent them, he saw their potential and popularized their use. The revolutionary machines provided the proper conditions for premature infants to develop after birth, with the goal of keeping them isolated, clean, and warm (and they are still used today).

When Couney told Beth’s parents he could help their newborn, they hesitated at the thought of their daughter becoming part of a sideshow attraction. But they were desperate to keep her alive, so their decision became clear.

“[My mother] didn’t want me to be known as a freak; she was against the whole idea. And Dr. Couney came to the hospital, and he must have been very convincing, because he left with me,” Beth Allen, now 81, of New Jersey, tells Mental Floss. “Her doctors urged her to send me to him.” Upon leaving Coney Island three months later, Beth weighed five pounds.

Couney's baby incubator shows offered care for preemies that was actually far ahead of its time. In an era when medical providers lacked knowledge and technology to help premature infants survive, Couney saved thousands of lives—and did so even as the American eugenics movement argued that helping such “weaklings” was a drain on medical resources. Couney proved that, with the right care, these newborns had a chance at life.

Incubator Innovations

Before incubators were widely available, efforts were sometimes employed to at least try and save premature infants. Midwives and mothers warmed preemies in baskets with heated water and blankets. Yet the odds of survival, especially for babies born under 4.4 pounds, were very slim, according to Dawn Raffel’s 2018 biography, The Strange Case of Dr. Couney: How a Mysterious European Showman Saved Thousands of American Babies.

In Germany in the mid-1800s (and even earlier in Russia), infants were placed in “warming tubs” where they would lay on a dry bed surrounded by hot water. Then, around 1880, French obstetrician Stéphane Tarnier introduced prototypes at the Paris Maternité hospital of what would become a more popular incubator model. Tarnier was inspired by incubators for birds’ eggs that he saw at the Paris Zoo.

Tarnier’s apprentice and successor at the hospital, Pierre Budin, opened an entire nursery dedicated to the care of premature infants. Even while the hospital employed both incubators and wet nurses, parents remained hesitant, partly because hospitals were widely regarded as deadly to infants at the time—environments where infections spread quickly.

By the late 1880s, according to a 2022 article in the journal Pediatrics, engineer Alexandre Lion of France had created an upgraded version of Tarnier’s incubator with improved ventilation and other features. But Lion needed a way to show the world his machine. He decided to hold educational incubator exhibits with live infants in France, then in Amsterdam and Berlin.

‘A Concept That Worked’

Couney, as well as other showmen, attended Lion’s shows and recognized their potential to save lives—and, yes, make a profit.

“This was a concept that worked—having these incubator pavilions, providing for some care, invit[ing] hospitals and doctors to send in babies, and tak[ing] care of these babies while they were seen by the public coming by and paying for this,” Thijs Gras, a Netherlands-based historian and author of the Pediatrics article, tells Mental Floss.

Researchers like Gras and Raffel have noted that it was really Lion’s exhibits that inspired Couney to launch shows of his own. These findings contrast the narrative Couney told during his lifetime: that he started out as a protégé of Pierre Budin, and that Budin sent Couney to the Great Industrial Exposition of Berlin in 1896 to show off the incubators being used at Paris Maternité.

In Raffel’s research for her 2018 biography on Couney, she writes that Couney never really worked for Budin, nor did he hold an 1896 exhibition. He was not even a licensed medical doctor. “It was just this combination of no record of any medical licensing, no evidence that he was ever in any of those places he said he was in,” Raffel tells Mental Floss.

Couney’s Incubator Shows Are Born

Couney was born in Prussia as Michael Cohn in 1869. He changed his name after immigrating to New York at 18 years old, Raffel writes—though we don’t know much about his first decade in the city. (He officially became Martin A. Couney in 1903.)

In 1897, Couney held a baby incubator show at Earl’s Court in London using Lion’s incubator model. The exhibit was largely well-received in the press, so Couney returned to the U.S. where, he reckoned, he could do some good for premature infants and their families—and spread the word about the effectiveness of incubators.

“He just felt that these were babies who needed to be saved and he could do it,” Dr. Lawrence Gartner, a neonatologist and professor emeritus at the University of Chicago, tells Mental Floss. “He may have been driven by the fact that he could make money at this, but certainly it was part of his life to save these babies. And he made a show of it.”

In 1898, Couney held an exhibit at the Omaha Trans-Mississippi Exposition, and another at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York in 1901 (with a brief return to Paris in between).

‘All the World Loves a Baby’

For four decades, Couney continued to hold summertime sideshows at Coney Island and Atlantic City, as well as with other fairs and amusement parks across the country. His exhibits were widely known in the U.S. and beyond. Above the entrance to his exhibit, a sign read “All the World Loves a Baby.” People could look at rows of premature infants from behind the incubators’ glass windows.

At first glance, one might easily surmise that Couney was in it for the money. But his system of care was comprehensive and high quality, which is why so many of these infants survived—roughly 6500 to 7000 over the years, with Couney claiming an 85 percent survival rate. In comparison, the CDC once reported that at the beginning of the 20th century, for every 1000 live births in the U.S., approximately 100 infants died before their first birthdays.

Couney employed a small nurse-to-patient ratio, and his trained nurses fed babies breast milk in various forms while providing individual attention and physical affection. Good hygiene and cleanliness were top priorities. It wasn’t just incubators that saved the children; it was also the system of care the staff employed, Raffel says.

Couney charged his visitors an admission fee, which helped pay for the treatment of the infants. The exact amount changed over the years but eventually reached 25 cents, Raffel says. By 1903, Couney opened his first show at Coney Island, designed to be educational as well as entertaining.

“These machines were first touted as, ‘It’s almost like a toaster oven; all you have to do is pop in a baby and everything is fine.’ And that isn’t true,” Raffel says. “You need a lot of skilled people and a lot of care, and [Couney] was really the one who stuck with it”—particularly in the U.S.

Couney even held reunions for the once-premature infants years after they were in his care—another Barnum-esque trick to demonstrate the success of his methods.

The Eugenics Movement Emerges

As Couney demonstrated the possibility of saving preemies’ lives, the eugenics movement in the U.S.—which had emerged in England in the late 19th century—spread the terrifying notion that humans could manipulate the gene pool to prevent “undesirable” births. Eugenicists argued that society’s focus should be on the eradication of traits held by “unfit” individuals, which they believed included those with disabilities and ethnic and religious minorities. Premature babies were lumped into this category, since disabilities were a possible complication of premature birth.

The eugenics movement in Britain and elsewhere had focused primarily on selective breeding for “positive” traits, but in the U.S., eugenicists advocated for the elimination of “negative” traits. Raffel describes Couney as holding his baby incubator shows “in the shadow of the eugenics movement”—though Couney neither addressed eugenics directly nor faced direct criticism from eugenicists.

But the contrast among the two coexisting ideologies was striking. With the right care, Couney argued, you could save premature babies—a distinction from the eugenic theory that saving certain lives was a burden to society.

A vast majority of Couney’s babies went home after just a few months, and many lived for decades, helping to disprove the eugenicists’ basic philosophy. Meanwhile, by the onset of World War II in 1939, eugenics had fallen out of favor with the public and the subset of the scientific community that had embraced its ideology in its early years.

Praise (and Doubts) for Couney

Among many pediatricians, at least in New York, Couney had a reputation for saving lives, which is why so many hospitals and clinics sent premature infants his way.

Still, in Couney’s time, other members of the medical community denounced the sideshows as an attempt to make a spectacle for profit or simply ignored Couney, Raffel writes. According to a 2005 article in The New York Times reporting on Couney’s induction into the Coney Island Hall of Fame that year, “History did not know what to do; he was inspired and single-minded, distasteful and heroic, ultimately confounding.”

Even though Couney charged visitors an admission fee, Raffel says this was happening at a time when he was offering a rare service with a positive result. “The hospitals were literally telling patients, ‘The only way your child is going to survive is if you go to Coney Island,’” Raffel says. Beyond just treatment, though, Couney was also launching “propaganda on behalf of preemies,” Raffel writes.

From Amusement Parks to Hospitals

In 1911, Dreamland Park—where one of Couney’s two exhibits at Coney Island was located—had a fire that burned down the Infantorium where the babies slept. Luckily, none was injured. But shortly afterwards, the president of the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children stated that premature infant care should happen only in hospital settings.

This was easier said than done. While some regional medical centers began adopting incubator technology in the 1920s, neonatology was not yet recognized as a specialized medical field, and equipment was expensive. Medical facilities also struggled with the necessary staffing and individual care. So Couney’s shows, given their high success rates, stayed open until 1943.

Couney’s professional relationship with Dr. Julius Hess, who designed incubators and is widely credited as the father of American neonatology, also contributed to greater acceptance of Couney’s methods in the medical community. Hess has frequently credited Couney with “having taught him quite a bit,” Raffel says. “That’s partly how [Couney’s methods] started to become more integrated into this system of medical care.”

By 1943, in the same year Couney officially closed his Coney Island show, Cornell New York Hospital had opened the first dedicated premature infant station.

A Chance at Life

When Couney died in 1950, the study of premature infants was becoming more common, and neonatology was officially declared a medical specialty in 1960. Hospitals began building out sophisticated neonatal intensive care units, or NICUs—facilities that are now common in the care of premature babies. One in 10 infants is born prematurely today, with an 80 to 90 percent survival rate for those born at 28 weeks.

Couney helped popularize incubator technology and changed attitudes about premature infant care within the medical community and the public. His ideologies proved the fallacy of the eugenics movement underway in the U.S. He was ahead of his time.

Today, parents no longer need to worry about placing their newborn in the hands of a stranger in Coney Island. But in the early 20th century, it was a matter of life or death for the child. And despite being a fake doctor, or even a profit-minded showman to some, Couney gave premature babies a chance at life.