In 1939’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, idealistic young senator Jefferson Smith (Jimmy Stewart) commands the attention of the floor by going on an exhausting 23-hour filibuster in the hopes of condemning a corrupt senior senator (Claude Raines).

A filibuster of similar duration actually took place on the Senate floor in 1957, but the motivation for doing so was the moral opposite of Stewart’s ambitions. In an effort to thwart a key civil rights matter, Senator Strom Thurmond spent 24 hours talking, arguing, and making plans to urinate into a bucket.

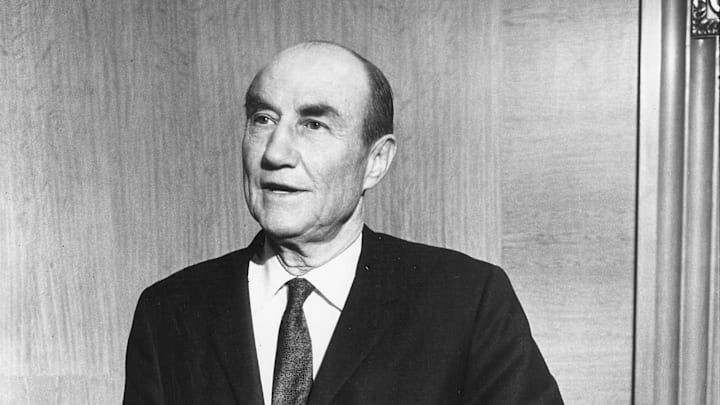

Filibusters are a nuisance tactic lawmakers use to hold the Senate floor in the hopes of stalling or avoiding a vote on legislation. While they can now be enacted via email, in 1957 a filibuster required a lawmaker to be physically present on the Senate floor, which is how Thurmond, a Democrat from South Carolina, came to seize the Senate’s attention for over 24 hours.

Elected to the South Carolina State Senate in 1932, Thurmond was vehemently opposed to racial integration and spoke out often against legislative attempts to enact federal civil rights laws. In 1956, he and 18 other Southern senators signed the Southern Manifesto, which opposed desegregation in schools.

It was little surprise, then, that Thurmond would oppose the Civil Rights Act of 1957. Thurmond physically prepared himself to have the stamina to delay the vote. He dehydrated his body by sweating in steam baths so he could take in liquids without making frequent trips to the restroom. If he did have the urge to go, his plan was to put one foot inside of a cloakroom and urinate into a bucket held by an unfortunate intern while keeping one foot on the Senate floor.

On August 28, 1957, Thurmond began his interminable stalling tactic. He droned on for hours, breaking only when another senator asked that he yield the floor briefly so something could be placed into the Congressional Record. Thurmond agreed, using the time to run to the bathroom.

So what did Thurmond actually say all that time? Nothing of substance. To protest the bill’s protection of voting rights, he argued states already had such laws in place and then proceeded to read the dry language that explained policies for each state.

When that well ran dry, Thurmond recited court decisions, read newspaper articles, and even invoked the Declaration of Independence. To give his voice a break, co-conspiring senators asked questions with verbose set-ups.

In total, his filibuster lasted 24 hours, 18 minutes, with Thurmond finishing by saying that “I expect to vote against the bill,” a comment that forced those in attendance to laugh.

Despite his marathon efforts, the bill passed; Thurmond later argued that his views were not racist but rooted in a desire to minimize federal authority. The proclamation rang hollow for those who had heard him voicing opposition to “social intermingling of the races.” He retired shortly before his death, age 100, in 2003. At the time, he was the longest-serving senator in history (Robert C. Byrd of West Virginia later surpassed him to claim that title).

At no point during his 24 hours on the Senate floor did Thurmond mention that in 1925, at age 22, he had fathered a child with Carrie Butler, his family’s 16-year-old Black housekeeper. His biracial daughter, Essie Mae Washington-Williams, kept her relationship to Thurmond a secret until his death.

“I never did like the idea of his being a segregationist, but that was his life, and there wasn’t anything I could do about that,” Washington-Williams said.

[h/t NPR]