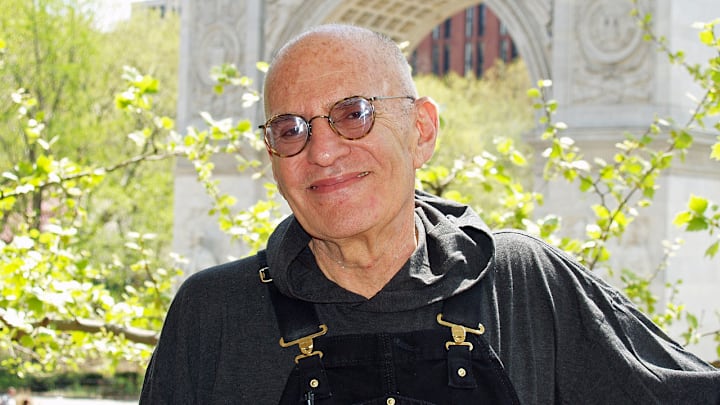

American writer and activist Larry Kramer is remembered as a leading figure in the LGBTQ+ civil rights movement, particularly in the earliest years of the HIV/AIDS pandemic. While co-founding two of the most influential HIV/AIDS organizations in the U.S., he still had time to pen a landmark play and be nominated for an Academy Award. Here are more facts about Kramer’s amazing legacy.

Born | Died | Known For |

|---|---|---|

June 25, 1935 | May 27, 2020 | “The Normal Heart,” founding Gay Men's Health Crisis and ACT UP |

1. Larry Kramer had a mental health crisis in college that shaped his future.

Kramer was born in Bridgeport, Connecticut, in 1935, the younger of two sons in a middle-class family. His father was an attorney for the government and his mother helped the family survive the Great Depression by working as a teacher.

Like his father and older brother, Kramer attended Yale University, but he struggled with loneliness and academic challenges. He also grappled with his sexual identity, believing he was the only gay student on campus. He attempted suicide in his freshman year. Fortunately, with therapy, he began to come to terms with his sexual orientation. He soon embarked on a romantic relationship with his German professor and found a sense of belonging in the Varsity Glee Club. Even decades later, Kramer confided that the memory of his mental health crisis in college always haunted him.

2. Kramer was nominated for an Oscar.

After he graduated with a degree in English in 1957, Kramer’s career began in the movies. He got his foot in the door at Columbia Pictures as a teletype operator and worked up the ladder to the story department, where he rewrote scripts. He did similar work in London for United Artists. Kramer began his screenwriting career crafting dialogue for the teen comedy Here We Go Round the Mulberry Bush, followed by his adaptation of D.H. Lawrence’s novel Women in Love, which earned him an Academy Award nomination in 1971.

3. A box office bomb set him up financially.

Kramer penned the script for the 1973 musical remake of Frank Capra’s 1937 film Lost Horizon. Like the airplane in Capra’s version, the musical crashed and burned at the box office. Kramer once said he considered it the “only thing I’m truly ashamed of.” But there was one major consolation: the well-negotiated fee Kramer received, skillfully invested by his brother, provided a lifetime of financial security.

4. Kramer wrote an incendiary novel criticizing gay men.

In 1978, Kramer published an autobiographical novel, titled Faggots, that satirized a libertine clique of gay men who lived in Manhattan and summered on Fire Island. Kramer’s middle-aged protagonist, Fred Lemish, struggles to find a meaningful relationship with his crush, Dinky Adams, among the shallow party animals who have sex at the drop of a hat and use drugs indiscriminately.

Faggots offended gay men, who had only recently gained the freedom to live more openly, and it shocked straight readers with its graphic sex scenes. “The straight world thought I was repulsive, and the gay world treated me like a traitor,” Kramer said. “People would literally turn their back[s] when I walked by.” Despite (or because of) the uproar, Faggots has become one of the most popular gay novels in history.

5. He helped start the world’s first AIDS organization in his living room.

In 1981, reports emerged about young gay men suffering from unusual illnesses, including pneumonia and cancer. Initially dubbed Gay-Related Immune Deficiency (GRID), the syndrome was caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), but researchers didn’t discover it until 1984. The disease was eventually renamed Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS).

Most medical institutions were slow to recognize the crisis as scores of young, previously healthy gay men died. Kramer gathered 80 people in his apartment and they took matters into their own hands, launching a hotline, a comprehensive newsletter, and support services under the name Gay Men’s Health Crisis. The following year, the group raised $100,000 for AIDS research. With 150 volunteers, GMHC operated without funding from the government or the medical establishment to provide vital information and resources.

6. His famous 1983 essay galvanized AIDS activists.

Kramer warned that AIDS would become a global epidemic to anyone who would listen and castigated people in power who ignored the threat. In September 1982, he spoke to a reporter about losing friends to AIDS and witnessing inadequate treatment in Manhattan hospitals. He became known as the angriest man in the world. But government agencies, elected officials, and health institutions failed to respond with sufficient urgency.

Six months later, his furious op-ed, “1112 and Counting” (a reference to the number of AIDS cases then diagnosed) was published on the cover of The New York Native, an LGBTQ+ newspaper. “If this article doesn’t scare the sh*t out of you, we’re in real trouble. If this article doesn’t rouse you to anger, fury, rage, and action, gay men may have no future on this earth. Our continued existence depends on just how angry you can get,” he began.

Kramer cited the appalling statistics and the fact that doctors had no idea what caused AIDS two years into the crisis. He criticized the institutional inaction as well as what he perceived to be the apathy of his peers, and he urged them to fight for their lives.

7. His 1985 drama The Normal Heart changed the national debate around AIDS.

Kramer’s autobiographical 1985 play, The Normal Heart, dramatized his experiences during the early years of the AIDS crisis. The story followed Ned Weeks, a writer who struggles to establish a grassroots movement to fight AIDS while his boyfriend is dying of the disease. It premiered off-Broadway at The Public Theater in 1985 and ran for 294 performances, followed by productions around the country and on Broadway in 2011, which won the Tony Award for Best Revival of a Play. The productions launched national conversations about AIDS, and today it’s considered a groundbreaking work in LGBTQ+ theater. In 2014, The Normal Heart was adapted into a highly acclaimed HBO film directed by Ryan Murphy and starring Mark Ruffalo as Ned Weeks.

8. Kramer helped found ACT UP after GMHC ousted him for being too militant.

In 1983, Kramer was banished from GMHC, the organization he helped create, for being too loud and confrontational. Four years later, he helped organize ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), a direct-action advocacy group to pressure the government and drug companies to develop effective, accessible AIDS treatments. ACT UP embraced the notion of using bold strategies and civil disobedience tactics. They drew attention to the need for radical action, which led to major advancements in AIDS research, treatment, and prevention.

In 1988, Kramer was diagnosed as HIV-positive, and he intensified his confrontational style, often using anger and public demonstrations to demand action from the government.

9. Kramer eventually married his elusive crush from his controversial novel.

Kramer modeled his novel’s main character, Fred Lemish, on himself. Lemish’s sometime lover Dinky was also based on a real person, an architect named David Webster, who was Kramer’s intermittent boyfriend. After dating off and on in the 1970s, the two had no contact again until the mid-1990s, when Kramer asked Webster to help him find and renovate his dream house. They rekindled their romance, and this time, the relationship stuck. In 2013, the couple married in a Manhattan hospital where Kramer was recuperating from surgery.

10. He received numerous honors for his writing and activism.

Kramer was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for his 1992 play, The Destiny of Me, a sequel to The Normal Heart. He lost out to another drama that touches on the AIDS crisis, Angels in America: Millennium Approaches, by Tony Kushner.

In addition to his literary accolades, Kramer received several awards and honors for his activism, including the Human Rights Campaign’s National Leadership Award and the Public Leadership Award from the National Association of People with AIDS. Ironically, GMHC also honored him with a Lifetime Achievement Award in 2015. Kramer died of pneumonia at age 84 in 2020.