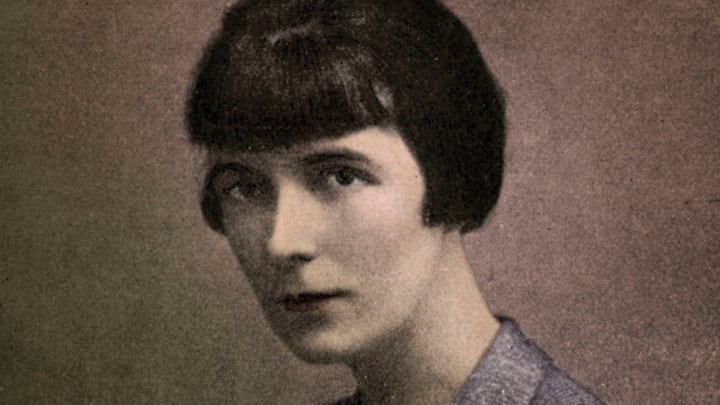

Today, Katherine Mansfield is considered one of the most influential modernist writers of the 20th century. In addition to publishing several short story collections—including In a German Pension (1911), Bliss and Other Stories (1920), The Garden Party and Other Stories (1922), and The Doves’ Nest and Other Stories (1923)—Mansfield was a prolific literary critic, producing more than 100 book reviews for The Athenaeum magazine. Although she has been dead for a century, her work and her advice still resonate today. “Risk! Risk anything!” she once wrote in her journal. “Care no more for the opinions of others, for those voices. Do the hardest thing on earth for you. Act for yourself. Face the truth.” Here’s what you need to know about Mansfield.

1. Katherine Mansfield published her first stories before she was a teenager.

Kathleen Mansfield Beauchamp was born on October 14, 1888, in Thorndon, Wellington, New Zealand, to a prominent local family. She began writing stories at a young age, and her first published works appeared in her school magazine when she was 9 years old. These stories were followed by “His Little Friend,” published on a page written by children in The New Zealand Graphic and Ladies’ Journal in 1900 under the name Kathleen M. Beauchamp. (Until the discovery of “His Little Friend” in the Wellington City Libraries’ collections in 2016, researchers believed Mansfield’s first commercially published work occurred in 1907.) Later, she would adopt the pseudonym Katherine Mansfield.

2. Her cousin was also a writer.

Mansfield’s passion for writing may have been encouraged by the example of her successful and famous cousin, Elizabeth von Arnim (born Mary Annette Beauchamp), who published her first work, Elizabeth in Her German Garden, to instant success in 1898. The two women didn’t become close until later in life, largely because Mansfield spent her early years in New Zealand and Australia-born von Arnim was living in Europe. But Mansfield likely took inspiration for several of her short stories from von Arnim’s works, including those featured in In a German Pension, whose narrator resembled the main character in Elizabeth in Her German Garden.

3. Mansfield considered a career as a musician.

Mansfield was a talented musician. She considered becoming a professional cellist until she began contributing regularly to her school newspaper. Her parents’ disappointment with her potential career path was also a factor in her pursuit of writing over music. “Father is greatly opposed to my wish to be a professional ‘cellist or to take up the ‘cello to any great extent—so my hope for a musical career is absolutely gone,” she wrote in a 1906 letter. “But I suppose it is no earthly use warring with the Inevitable—so in the future I shall give all my time to writing.”

4. She frequently wrote about New Zealand.

In 1903, Mansfield moved with her family to Europe; she went to school in England and toured parts of Belgium and Germany before returning to New Zealand in 1906. Mansfield often wrote about the country in her fiction, exploring themes of colonization, patriarchy, and the tensions between the landscape and human civilization. In 1908, Mansfield moved to Europe permanently, spending much of her time in London and establishing herself on the fringe of the famous Bloomsbury Group, whose members included Virginia Woolf, Leonard Woolf, and Lytton Strachey.

5. Virginia Woolf was jealous of her.

Mansfield and fellow modernist writer Virginia Woolf, who were both part of London’s thriving literary scene, first met in 1917. Despite Woolf’s initial skepticism about Mansfield’s appearance and mannerisms (in a diary entry, she wrote of Mansfield’s “commonness at first sight” and that she stank “like a … civet cat that had taken to street walking”), the two women became friends, and their friendship was both personally and professionally important. Even as they maintained a professional rivalry, Mansfield and Woolf greatly admired each other’s works. They were also heavily influenced by each other as writers. “You are the only woman with whom I long to talk work. There will never be another,” Mansfield wrote to Woolf. After Mansfield’s early death, Woolf said that, “I was jealous of her writing—the only writing I have ever been jealous of.” Woolf even described being haunted by Mansfield, “that strange ghost, with the eyes far apart, & the drawn mouth, dragging herself across the room.” She lamented that “K. & I had our relationship; & never again shall I have one like it.”

6. Woolf published one of Mansfield’s most important works.

One of Mansfield’s most important works, 1918’s “Prelude,” was the second-ever work (or arguably the third, depending on how you class the privately distributed Poems) published by Hogarth Press, an independent publishing company owned and managed by Woolf and her husband Leonard. (“Certain details reveal that the Woolfs were still printing amateurs,” the British Library notes. “[T]he story’s title, for instance, is misprinted as ‘The Prelude’ on several pages.”) It was later republished as part of a collection of short stories entitled Bliss and Other Stories in 1920.

Like many of her other famous short stories, “Prelude” is set in New Zealand; it explores themes of isolation and the complexity of family dynamics, perhaps reflecting some of Mansfield’s own conflicted feelings about her relationship with her family [PDF]. The story also engages with feminist issues, considering the role of women in relation to their social and political situation at the time of publication.

7. She frequently wrote stories inspired by her family.

Both In a German Pension and The Garden Party and Other Stories were almost certainly a salute to von Arnim, who visited Mansfield frequently in 1921, while they were both staying in the same region of Switzerland.

Von Arnim wasn’t the only family member who featured prominently in Mansfield’s works, either. According to Joanna Woods in a 2007 issue of Kōtare, her stories “Prelude” (1918) and “At the Bay” (1922) both feature less-than-flattering portraits of Mansfield’s parents, Harold and Annie Beauchamp, who had disinherited her: “Harold appears in the guise of the self-important Stanley Burnell,” Woods writes, “while Annie, as Linda Burnell, is depicted as an indifferent and distant mother.” Although “The Garden Party” (1922) offers a slightly more positive representation of Mrs. Beauchamp in the form of Mrs. Sheridan, the portrayal, according to Woods, “still emphasizes the gulf that [Mansfield] felt existed between her and the rest of her family.”

8. Mansfield and one of her husbands served as inspiration for D.H. Lawrence.

Mansfield was married twice and had several significant romantic relationships during her lifetime, including at least two with women. In 1909, she married George Bowden, a music teacher who was 11 years her senior, but according to Woods, “That night, before the marriage had been consummated, Kathleen abandoned her husband.”

Mansfield’s separation from her first husband appears to have led her mother to disinherit her. In fact, Mrs. Mansfield traveled all the way from New Zealand to England when she heard that her daughter was living with a woman, Ida Baker, instead of her husband. According to Mansfield’s biographer, Claire Tomalin, Baker’s family was warned about the dangers of lesbianism and Katherine was deposited in a Bavarian spa before Mrs. Mansfield returned home and disinherited her daughter.

Mansfield met her second husband, John Middleton Murry—then the editor of Rhythm, a magazine to which Mansfield submitted several short stories—in 1911. Although they separated several times, the couple married in 1918 and remained married until Mansfield’s death. They even helped inspire the characters of Gudrun and Gerald in D. H. Lawrence’s Women in Love, which tells the story of the rocky romantic relationships between two couples, Gudrun and Gerald, and Rupert Birkin and Ursula Brangwen, whom Lawrence modeled on himself and his wife, Frieda.

The portraits are unflattering, with both fictional couples coming across as tempestuous. They were, however, quite true to life. The two couples lived near each other in Buckinghamshire in 1914 and later in Cornwall. Mansfield and Lawrence were very close friends for a time, but they argued frequently and would often break off their relationship altogether. Complicating things, perhaps, was the reality that Lawrence had complex feelings for Mansfield’s husband, and Murry was attracted to Lawrence’s wife—and had an affair with her shortly after Mansfield’s death.

9. She was just 34 years old when she died.

Mansfield was diagnosed with tuberculosis in 1917 (some suspect she got the disease from Lawrence, though he wasn’t officially diagnosed until 1925). Mansfield traveled around Europe between 1920 and 1922 trying to find a cure. She was attended by various prominent physicians of the day, but her condition did not improve. Eventually, she traveled to Fontainebleau, where she stayed at the Gurdjieff Institute for Harmonious Development. She died there on January 9, 1923, from a pulmonary hemorrhage, apparently caused by running up a flight of stairs. She was 34 years old.

10. Mansfield was posthumously accused of plagiarizing Anton Chekhov.

Russian author Anton Chekhov was one of Mansfield’s favorite writers, and according to Melinda Harvey in Katherine Mansfield and Literary Influence, critics were comparing the two of them as early as April 1920, initially as a way of emphasizing Mansfield’s talent. Eventually, though, some critics suggested that Mansfield was doing more than paying homage to Checkhov.

One of her early stories, “The Child-Who-Was-Tired,” published in 1910, has received particular attention because of its similarities with Chekhov’s “Sleepyhead” (1888). In late 1951, The Times Literary Supplement featured a heated exchange between novelist E.M. Almedingen and Murry about the accusations. In the end, Murry acknowledged that there was “a strong prima facie case” for plagiarism.

Other strong parallels have since been noted between Chekhov’s work and Mansfield’s, including Chekhov’s “Not Wanted” (1886) and “The Grasshopper” (1892), and Mansfield’s “Marriage à la Mode” (1921); Chekhov’s “The Party” (1888) and Mansfield’s “The Garden Party” (1921); and “The Looking-Glass” (1885) and “Taking the Veil” (1922).