If you have ever found yourself surfing through television infomercials in the early hours of the morning and wound up with a novelty blender in the mail four to six weeks later, you have Philip Kives to thank. The Canadian entrepreneur pioneered the long- (and short-) form sales pitch on TV, peddling everything from Teflon pans to fishing lures to what may have been his crown jewel—the K-Tel series of compilation record albums, a brilliant way to market catalog music that acted as a vinyl version of Spotify and turned Kives and K-Tel from a success into a sensation.

And it all began with polka.

Record Setting

Kives (pronounced Kee-vuss) got off to an auspicious start with his business ambitions. As a child in 1930s Canada, he trapped weasels and sold their fur for 50 cents a pelt, a sales approach he later felt predicted his born-ready entrepreneurial mind. (Another version of his rags-to-riches tale has him dealing in gopher tails, which were profitable to turn into local authorities due to the animal's overpopulation in the region. Perhaps it was both.)

Eventually, Kives moved to Winnipeg, where he worked as a taxi driver and sold kitchen utensils door-to-door. When he was in his early thirties, Kives had made his way to Atlantic City, where the Boardwalk was home to a litany of street barkers peddling their wares—some genuine, many offering buyer’s remorse. But Kives honed his skills, and when he returned to Canada in 1962, he produced and starred in a television demonstration for a new wonder product. For five full minutes, Kives extolled the benefits of a frying pan, which allowed cooks to work with a nonstick surface. Since Kives paid for the airtime, it’s believed to be the first-ever television infomercial, though it wasn’t without its problems: The material wasn’t totally ready for its official roll-out, and wound up sticking to the eggs.

That wasn’t ideal, but the notion that television could reach a huge audience was intoxicating to Kives. “When you’re working in stores, you’re [pitching] to a dozen, a half dozen people at a time,” he told The Age in 1978. “I had heard of people here and there who were beginning to use television to demonstrate products and I said, Well, if that's the case, instead of [pitching] to a dozen people at a time, I can work to thousands of people at a time on television.”

The eventual success of these and other gadgets expanded the Kives empire. He traveled to Australia to sell the Feathertouch Knife, which was his first runaway hit. The blade was so sharp it could slice through a tomato without collapsing it and was also tough enough to eat through shoe leather, making it ideal for visual demonstration. Kives sold a million of the chef’s blades, netting $1 apiece. He also bought the rights to distribute items like the Pocket Fisherman portable fishing line from Sam Popeil, father of fellow infomercial pioneer Ron Popeil.

Compared to toiling on his family’s Canadian farm, product pitching was “easy,” Kives said. His pitches were often punctuated by a legend seen both on the screen and on packaging: “As Seen on TV.” Kives also utilized the now-iconic “But wait, there’s more!” Kives usually wrote and directed the spots, and enlisted Winnipeg radio voice Bob Washington to do the voiceover.

By 1966, Kives’s company, K-Tel—which was shorthand for “Kives Television”—was in full swing. That’s when Kives had an idea that would propel him into another stratosphere of success. He obtained the Canadian distribution rights to 25 Country Hits, a compilation record album of two dozen popular country and western tunes. Each track was a hit as opposed to the hit-or-miss arrangement of individual act records.

At the time, the concept of a compilation album was largely unknown to the record industry. Once an album was released, that music wasn’t really revisited. Kives was able to license singles from record companies for as little as 2 to 4 cents per track per record, helping them monetize their back catalog. In return, he could sell a new track arrangement to listeners who liked a genre but wanted a little variety. The hook was in the numbers. With “20 original hits” from “20 original stars” or “30 masterpieces,” people were sold on volume. Thanks in part to a Bobby Darin “bonus” single, 25 Country Hits moved 180,000 copies.

On Track

After success in his native Canada, Kives and K-Tel shifted focus to the United States. His third album after the psychedelic Groovy Greats was 25 Polka Greats, which moved 1.5 million units, making K-Tel’s compilation business a certified hit and something that would define their business in the 1970s.

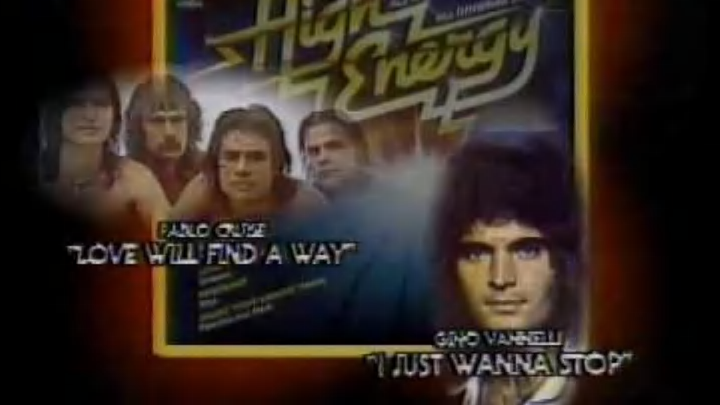

Titles like 60 Flash-Back Greats of the ‘60s (a four-record set), the funk-loaded Super Bad complete with the theme from Shaft by Isaac Hayes, and 24 Great Truck Drivin’ Songs featuring Hank Snow’s “I’ve Been Everywhere” were quickly snapped up.

The offerings were a success in large part because buying one of the albums at $4.99 was far cheaper for consumers than buying individual 7-inch singles. Sometimes, a label would sell a single to Kives provided he also grab a less successful recording. It was a win for all parties, though some listeners complained the audio quality on the records left a little to be desired. In an attempt to cram in as much music as possible on vinyl, the grooves were a little too close together, and some songs got clipped for time.

Compilations weren’t the only music effort Kives pursued. His Hooked on Classics saw the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra re-record classical greats with a disco pace, revising them for a contemporary audience. Like 25 Country Hits, it was marketed until it penetrated the cultural consciousness. (On Saturday Night Live, Dan Aykroyd lampooned Kives and his energetic delivery by shilling for the Bass-o-Matic, which could liquify a fish in seconds. It was a spoof of K-Tel’s Veg-o-Matic, which obliterated vegetables.)

What made the compilation albums distinctive was that Kives didn’t direct consumers to music stores for them. They were available in drug stores or department stores or hardware stores. Kives was also dealing directly with artists when possible. Liberace, he said, invited him over for dinner; Sammy Davis Jr., apparently unmoved by a business offer, yelled at him.

By one estimate, Kives sold more than 500 million copies of the records. Executives from CBS once traveled to Winnipeg to solicit marketing tips from Kives. By 1978, the albums made up 80 percent of K-Tel’s business, with $33 million spent on television advertising. The margins were slim but profitable: $4 million was a good year in the 1970s.

The compilation albums helped K-Tel thrive until the 1980s, at which point Kives made a series of self-admitted lousy business decisions. The company bought up real estate before an oil crash saw the market plummet; he also purchased rival Candlelight Music and subsequently suffered an $18 million loss. A Chapter 11 bankruptcy filing followed.

Kives rebounded in the 1990s, refocusing K-Tel on compilations and infomercials. His 101 Country Hits, a 10-CD set, was sold direct-to-consumer via TV spots hosted by musician Eddie Rabbitt; the same went for The Ultimate History of Rock'N'Roll, another massive collection endorsed by Bobby Sherman.

Many of these spots drew in viewers with a sense of urgency. There was no point in waiting because the first callers would get another CD or record for free. The compilations and the percussive ad pitches were emulated by Now That’s What I Call Music!, an assortment of contemporary chart-topping singles that debuted in the UK in 1983 and the U.S. in 1998. Music assortments rather than albums would become the dominant way of distributing music, particularly when streaming became viable.

But Kives was more than just an inspiration for today’s streaming wares. Because K-Tel owned more than 200,000 songs, he was later able to help populate Apple’s burgeoning iTunes format. Today, K-Tel is still in business, licensing songs for film and television: They helped place “Jingle Bell Rock” by Bobby Helms in season 2 of Stranger Things.

Kives never stopped peddling the As Seen on TV line-up. He was in constant search of products like the Fishin’ Magician and the Miracle Brush, which was really just a glorified lint roller. A see-through birdhouse (it was called, with a decided lack of sensationalism, The Birdhouse) allowed consumers to peer at bird eggs through transparent plastic.

By the time he passed away at the age of 87 in 2016, K-Tel had made its mark and Kives had a compilation of his own—one success story after another.

Read More About Music History:

A version of this article originally published in 2022 and was updated in 2024.