Bob Stoldal woke up one night and couldn’t understand what he was seeing. There, on his television, was Bullitt, a crime drama starring Steve McQueen that remains memorable for having one of the best car chases ever captured on film.

The reason it was odd was because Bullitt, which had opened in October 1968, was still playing in theaters around the country. It should have been months, if not years, before the film made its way to network television. And when it did, it was unlikely to premiere at 3 a.m., which is when Stoldal found himself watching it.

Then Stoldal remembered who owned KLAS, the local CBS affiliate station where Bullitt was playing and where he was a news director. It was Howard Hughes, the famed aviator and reclusive billionaire. Somehow, Stoldal would later learn, Hughes had managed to convince Warner Bros. to let him air the movie.

Unusual? Not for Hughes, who owned the channel less for its profit potential and more because he wanted to treat it like his own personal streaming library. Decades before people could queue up a movie on demand, Hughes could play his favorite films, including Bullitt, whenever he wanted.

Hughes Makes a Bet

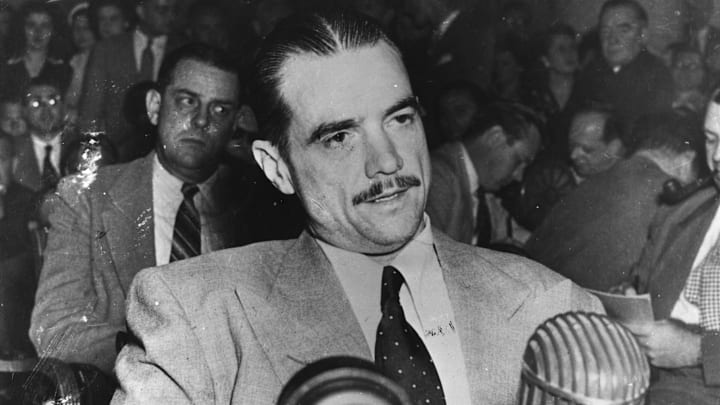

Thanks to his father’s fortune (the elder Hughes had invented an oil drill bit that could penetrate hard rock), Hughes had led multiple lives: He’d been a pioneering aviator, a socialite, and a movie mogul

(he had once been a film producer and director and was briefly the owner of RKO Pictures). By the 1960s, he was ready to enter the final phase of his life—this time as a recluse. A 1946 aviation accident left Hughes in chronic pain that led to an opiate addiction; eventually, a fear of germs and his obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) led him to withdraw further and further into seclusion until he had virtually dropped out of public view.

Las Vegas held some sway over him. He had been there during World War II and returned in 1953, leasing a small bungalow that had once been part of a larger motel; he dubbed it “the green house” for its green exterior paint. Hughes lived there the better part of a year before leaving town and with orders not to disturb the inside in case he opted to return. (He never did.)

A more permanent trek to Vegas came during Thanksgiving 1966, when Hughes, then 60, went back on his own private train. He was looking to have even more influence there than he possessed in California.

“I’m sick and tired of being a small fish in the big pond of Southern California,” Hughes had once reportedly complained. “I’ll be a big fish in a small pond. I want people to pay attention when I talk.”

The “talk” was more hypothetical than anything: Hughes really spoke to no one outside of his inner circle. After arriving in Vegas, he was whisked off without any public declaration of his arrival. It took the local Las Vegas press days to discover he was in town.

Hughes headed directly for the Desert Inn on Las Vegas Boulevard, taking up both upper floors, and proceeded to stay right on through New Year, paying $250 each night for the accommodations. When the hotel’s operator grew irritated over Hughes’s extended stay, Hughes simply bought the property outright for $13.25 million.

Hughes confined himself to the hotel; he was an avid television viewer, primarily watching movies. But his options were somewhat scarce. There was no cable, no video cassettes, and little else to see but whatever was on one of the three major television networks: CBS, NBC, and ABC. Hughes preferred CBS affiliate KLAS, which had been broadcasting since 1953 and was owned by publisher Hank Greenspun. The channel offered local news, CBS programming, and, of course, movies.

But Hughes had a major problem with KLAS. His habits involved watching television at all hours of the night due to his insomnia. His prime viewing window was from midnight to 6 a.m. KLAS, however, signed off for the day at 11 p.m. sharp; the other networks had no all-night schedules.

There were other problems. When Hughes missed a portion of a movie, he had one of his employees call KLAS and request that it be restarted. Other times, he demanded specific movies be programmed—mostly Westerns and aviation thrillers. This happened often enough that Greenspun later recalled issuing Hughes an ultimatum.

“Why doesn’t he just buy the thing and run it the way he wants to?” Greenspun barked.

Most people would laugh off such a notion. Hughes, an inveterate spender, did not. He and Greenspun negotiated the outright sale of KLAS, which Hughes acquired in September 1967 for $3.6 million. That meant Hughes now had full control of the station, which often left the other KLAS viewers in a state of confusion.

The Hughes Network

The surprise screening of Bullitt was just one of many irreverent decisions made by Hughes for KLAS. Movie would be restarted according to his whims. Sometimes, he’d have someone phone in and order a new movie to begin airing immediately. This meant that Vegas residents tuned in to KLAS could be watching a film, only to have it suddenly start from the beginning or switch to another film entirely.

“The station was for Howard Hughes back in the ’60s his own private movie projector, his Redbox, if you [will],” Gary Waddell, a former KLAS anchor, said in 2018.

KLAS wasn’t the only investment Hughes made in Vegas. Over the years, he spent an estimated $300 million, including five casinos and assorted real estate, helping define the Vegas Strip for decades to come. In doing business there, Hughes was able to take Vegas’s reputation of being a mafia stronghold and give it a more polished and professional veneer.

“He cleaned up the image of Las Vegas,” Hughes employee Robert A. Maheu told The Las Vegas Review-Journal. “I have had the heads of large corporate entities tell me they would never have thought of coming here before Hughes came.”

By the time Hughes left Las Vegas in 1970, he was considered one of the founding fathers of the resort city. For a time, he was Nevada’s third-largest land owner. He died in 1976 at the age of 70 having never returned to the city he redefined.

Now owned by Nexstar Media, KLAS is still broadcasting. Oddly, the little green bungalow that Hughes once called home in 1953 is situated in the station’s parking lot.

Read More About Television: