By the time Megan Jasper hung up the phone, she had done more to define the language of grunge than practically anyone.

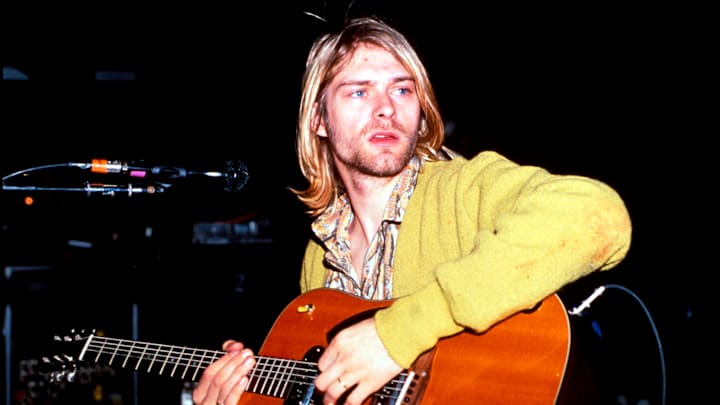

It was late 1992, and Jasper, a onetime receptionist for Sub Pop Records, an alternative label based in Seattle, had been phoned by Rick Marin, a freelance reporter for The New York Times. Marin was seeking information about the so-called grunge scene of the city—one that had grown to usurp rock on the airwaves and had made Kurt Cobain and Nirvana the new idols of the music industry.

Marin asked Jasper what sort of slang terms grunge aficionados tossed around. She rattled off a few—wack slacks, flippity-flop, lamestain. This, Jasper insisted, was the lexicon of those who worshipped at the cardigan altar of Cobain, Pearl Jam, and others.

A short time later, the Times piece on the rise of grunge ran, complete with a sidebar on the vernacular Jasper had shared.

No one seemed to realize she had simply made most of it up.

Getting the Dirt

“Grunge” was never a label that was particularly embraced by all of the bands who came to represent the musical genre, but there was no question it was a phenomenon. Rising out of the Seattle rock scene of the 1980s and bands like Soundgarden, the Melvins, and others, grunge was defined by a kind of sadcore sound and an aesthetic rejection of the hair band era. Grunge acts didn’t twirl microphone stands; lead singers didn’t do splits. Hair went from big to unwashed.

When the sound began to escape Seattle and spread throughout the country, the mainstream media quickly moved to provide explainers to puzzled Baby Boomers. Grunge seemed less like a rock genre and more of a lifestyle movement.

There were issues with this level of scrutiny. Record labels and artists in and around Seattle weren’t keen on being defined by a locale; nor did they particularly feel like cooperating with a media they felt either misunderstood their work or were dismissive of it.

That attitude extended to Megan Jasper. As a former office worker for Sub Pop, which had ushered bands like Nirvana, Soundgarden, and Mudhoney into the world, Jasper seemed adjacent to the grunge movement and well-positioned to speak on it. But Japer was also irreverent, a trait that came to mind when Marin phoned Sub Pop co-founder Jonathan Poneman. Poneman, who had been forced to lay off some company employees, including Jasper, referred the Times to her.

When Marin phoned her in 1992 to talk about grunge and its influence on fashion—she was working for Caroline Records at the time—she was, as a mischievious Poneman had predicted, put off by his line of questioning.

“They were doing a huge feature on grunge in Seattle,” Jasper told The World in 2018. “The journalist said, ‘We would like to share a lexicon of grunge. Every subculture has a different way of speaking and there’s got to be words and phrases and things that you folks say.’”

Marin had the right idea. Subcultures often develop their own subversive language that helps bond them and enhances the feeling that they’re in exclusive company. It happens in everything from multi-level marketing to cults.

But grunge did not, in fact, traffic in an abundance of slang. While grunge had certainly entered the public discourse, it had not been the start of any glossary of grunge terms.

“And I thought ‘really?’” Jasper told KNKX in 2020. “I thought ‘Sure, but there really wasn’t a secret language. It seemed like a fairly bizarre request. So, I just thought, ‘Sure. You want a lexicon? I will totally give you a lexicon.’”

So Jasper decided to make them up. Among the words she pulled from the ether that later ran in The Times:

Wack Slacks: a pair of tattered jeans

Plats: platform shoes

Swingin’ on the Flippity-Flop: hanging out

Harsh Realm: a bummer

Cob Nobbler: a loser

Lamestain: an uncool person

Fuzz: wool sweaters

According to Jasper, Marin seemed credulous about the words, so she kept going. “I thought that this was all going to end with him going, ‘Oh come on!’” Jasper said. “But it never happened.”

Misinformed

Jasper had made similar claims to a British magazine, Sky, which she also felt was looking at the grunge scene askance. Between the two publications—and one band, Mudhoney, catching on to Jasper’s joke and deciding to regularly drop the made-up terms into interviews—the public at large assumed words like cob nobbler were spoken throughout the Seattle scene.

This came as a surprise to Jasper, who didn't believe the silly terms would ever really see print. When her mother phoned her and told her to look at the November 15, 1992 edition of the Times, she realized she had been taken at her word.

In March 1993, Chicago publication The Baffler ran a story criticizing both the Times and Sky for falling victim to Jasper, who admitted to making up the terms. This, in turn, prompted a call to Jasper from an editor at The New York Times.

Instead of confessing, Jasper insisted they were real—she was fearful, she said, of Marin or his editor losing their jobs. Confused, the Times reached out to The Baffler, which insisted their Jasper story was accurate. Jasper eventually admitted to the prank.

(Marin’s editor, Penelope Green, told The Ringer that she had written up a correction, but that it never ran.)

Jasper later returned to Sub Pop, eventually becoming its CEO. And while wack slacks never caught on, there was a rush of T-shirts and other apparel that were emblazoned with harsh realm and other Jasper-coined phrases. Those new to the grunge “scene” incorporated it into their speech. It may have been said ironically, but grunge still had its share of lamestains.