When Ken and Beth Kiessling of Arbutus, Maryland, purchased tickets to see Gallagher at the Fish Bowl Inn in 1998, they were excited. The prop comic had headlined numerous specials on Showtime and was well-known for his signature bit: Smashing watermelons and other perishables with a giant hammer dubbed the Sledge-o-Matic.

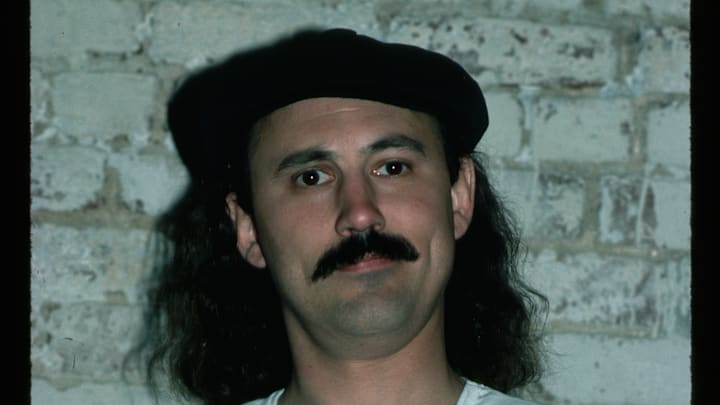

As expected, gooey bits of food showered spectators in the front rows. Gallagher, in his trademark beret, striped shirt, and mustache, atomized food and offered wordplay. (“People, you don’t have to study the orange juice carton just because it says ‘concentrate.’”)

It was not until after the show that the Kiesslings were informed by a journalist for the Baltimore Sun that while they had seen a Gallagher, they hadn’t seen the Gallagher. The man on stage was Ron Gallagher, who bore a striking resemblance to his older brother, Leo—the Gallagher who had invented the Sledge-o-Matic, vegetable violence, and practically the entire act. It was Leo who had appeared on Showtime and who had been in the comedy business since the 1970s. Ron was a kind of tribute act. The way people performed as Elvis Presley, he reasoned, was like how he performed as his older brother.

This was a kind of comedy franchise, with the Gallagher brothers doing for stand-up what McDonald’s had done for hamburgers. But it wouldn’t be long before Leo felt that the tribute was turning treacherous, that Ron was not merely honoring the original Gallagher—in the eyes of the audience, he was becoming Gallagher.

The Melon Smasher

Leo Gallagher was born in Fort Bragg, North Carolina, on July 24, 1946. His brother, Ron, followed five years later. (There were four Gallagher kids in all.) Their father, Leo Senior, owned a roller-skating rink, which was undoubtedly fun for his kids. But their parents also worked a lot, leaving Leo, as the oldest, to watch out for his younger siblings.

“My mother and father both worked, and Leo took care of the rest of us,” Ron said in 1996. “While babysitting, he would sit us down in the living room and practice his routines, and then direct us in little shows. He was a very good director. He really ran us through our paces. I idolized my big brother. I still do.”

When Leo was 10, the Gallaghers moved to Tampa, Florida. Later, he attended the University of South Florida and graduated in 1970 with a degree in chemical engineering. Conventional jobs did not appear to suit Leo very well: In one stint as a salesman, he felt compelled to come to work dressed as an old-time gangster, complete with a fake machine gun.

Odd jobs followed, as did work as a roadie for musician Jim Stafford. Soon Leo was growing comfortable on stage and developing a comedic persona that was a combination of observational humor and prop comedy. (At one point, he traveled with 15-foot lockers full of stage gimmicks.) Playing on the Veg-o-Matic vegetable chopper device, Leo came up with the Sledge-o-Matic, an oversized mallet that could decimate watermelons, lettuce, and other food.

Audiences apparently found this combination of comedy and destruction cathartic. His fame grew with appearances on The Tonight Show and on Showtime, which signed him to a deal in 1980 and eventually aired 16 of his specials. By the end of the 1980s, it was difficult not to be at least somewhat aware of Leo Gallagher and his pulping of fruit. True Gallagher devotees wore raincoats to his shows to keep their clothes from being sullied.

Ron Gallagher, meanwhile, was in a decidedly less amusing profession: He sold heavy equipment like bulldozers. But a recession in 1989 cut deeply into his business, and he began to think of alternatives.

Ron had accompanied Leo on tour at times, observing his act and absorbing it to the point where, according to Ron, he could correct Leo if he messed up his own material. They also bore a strong resemblance to one another. Once, when Ron donned a wig to give him an appearance closer to that of Leo (who had longer hair), crew members confused him for Leo. And there was the time Leo invited Ron to run on stage, tricking the audience momentarily until Leo joined him.

In the ultimate meta moment, Leo even asked Ron to smash a watermelon for him on stage, so Leo could take in the bit from a seat the way an audience member would.

“I had been to so many of his shows that I already knew all of his material,” Ron said in 1992. “So, he said, ‘Why don’t you do some of my old stuff? Take some of my early stuff and go around and try it.’”

Leo, who had been performing for well over a decade by this point, had discarded some of his older material. He agreed to let Ron perform it along with the Sledge-o-Matic finale with a handful of conditions. For one, he didn’t want Ron to book larger venues like the ones Leo toured. Ron could tackle small clubs. For another, he wanted Ron to make it clear that spectators would be getting Ron, not Leo.

Ron eagerly agreed. After getting over his stage jitters in a Miami club, Ron began touring, offering a Gallagher-esque experience at a discount. Tickets to the original Gallagher might be $20 to $30, costing the venue upwards of $40,000. To see Ron was a far more reasonable $10 admission, or $10,000 for the club.

“There are so many out-of-the-way-places I can’t go to,” Leo said in 2002. “I wanted my brother to see what it was like to be a comedian. I wanted my older jokes to continue.”

Ron stuck to the smaller dates, and business was brisk. He soon dubbed himself Gallagher II, Gallagher Too, or Gallagher—the Sequel. He dropped into supermarkets to pick up fruit for destruction and insisted that he was merely paying homage to his older brother.

It was hard to get people to believe it. “I can tell people I’m not Gallagher but they don’t believe me,” Ron said in 1994. “Then it’s like Gallagher is being rude, trying to avoid his public. A lot of times I argue with people after a show who swear I’m just under cover, playing the smaller places to try out new material or whatever.”

By the late 1990s, Ron was booking 200 dates a year. But Leo’s preference that Ron identify himself as a faux Gallagher had not gone so smoothly. Part of it was Ron’s eagerness to duplicate Leo’s look: beret, striped shirt, black pants, mallet. The other issue was in clubs and managers creating the advertising. Even when they used “Ron Gallagher,” it didn’t have the intended effect. Because most people knew Gallagher as simply Gallagher and not Leo Gallagher, printing his full name didn’t diminish any confusion. In fact, most people seemed to believe they were paying to see Gallagher, insisting Ron was Leo even after Ron introduced himself as Leo’s brother.

“I say Ron Gallagher in the advertisements,” Ron’s booker, David Herman, told the Baltimore Sun in 1998. “If they don’t know, they don’t know. I’ve never had to give a refund. I don’t think they even know or care.”

But someone did care: Leo. The original Gallagher had embraced the nascent internet of the 1990s, setting up a website and email account. Messages began pouring in asking him if he was performing at this or that venue—all dates that had been booked by Ron in increasingly bigger theaters. Clearly, consumer confusion had become rampant. And Leo was now in the position of having to take action against the doppelganger he had helped to create. He traded his sledgehammer for a gavel and sought help from federal court.

Gallagher v. Gallagher

In November 1999, Leo filed a federal lawsuit in Michigan district court alleging that Ron had violated Leo’s publicity and trademark rights. He also cited false advertising and unfair competition. He sought an injunction barring Ron from positioning himself as the world-famous Gallagher. Ron countered by contending that Leo had given his blessing for the copycat act and that no restrictions had ever been placed on it.

In July 2000, Judge Paul Borman sided with Leo. In a singularly bizarre ruling, Borman wrote that Ron must not use “a sledgehammer or other similar device to pulverize watermelons, fruits, food or other items of any kind,” nor could he sport the “beret, striped shirt, long hair and mustache” that had become synonymous with Leo. And he could not advertise himself as simply “Gallagher” or refer to the mallet as the “Sledge-o-Matic.” Watermelons were also out of the question.

The edict did not bar Ron from performing, but it’s fair to say it made him reluctant. A planned performance in March 2001—his first since the injunction—was canceled when Ron learned that the club’s advertising was still too vague: Older photos demonstrating Ron’s likeness to Leo were still being used. Ron refused to appear, saying that he was apprehensive Leo would drag him back into court.

For his part, Leo remained irked by his brother. He shaved his head completely in 2000, partly to pursue a new look and partly, he said, to lessen audience confusion as it related to Ron. He felt Ron had been too aggressive in echoing his act, though Ron once estimated roughly 50 percent of the material was his own. Later, he raised it to 80 percent.

Whether the brothers were ever close is hard to gauge. Ron once said he spoke to Leo once every couple of weeks but that they rarely saw each other, as they toured different areas of the country. After the lawsuit, it seemed as though their relationship was seriously frayed. In 2013, Leo said he hadn’t spoken to Ron in the previous 20 years.

Leo Gallagher died at age 76 in 2022, his eulogies a mixture of respect for his early success and criticism of some of the racially-charged humor that had become part of his act. Following the lawsuit, Ron never resurfaced as a Gallagher clone. According to Leo, by 2002 he was out of the comedy business.

While Leo was understandably frustrated by what he perceived as Ron cloning him, audiences didn’t seem to mind. Ken Kiessling assumed he saw Leo back in Maryland in 1998. When told he had seen Ron, he seemed unperturbed.

“They really look alike,” Ken said. “I couldn’t tell any difference. I still had a great time.”

Read More About Entertainers: