Table of Contents

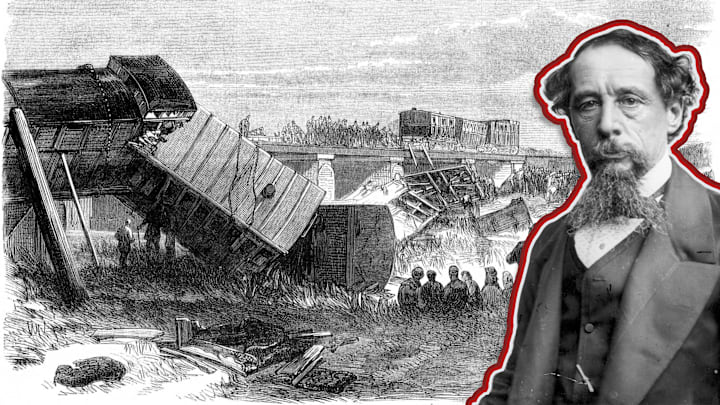

On June 9, 1865, a stunned Charles Dickens crawled out of a derailed train carriage hanging precariously off a bridge near Staplehurst in Kent, England, to a scene of pure chaos. Below him, he could see other cars from the train mangled and broken in the shallow river; 10 people had been killed and more than 40 others injured. The Oliver Twist and Great Expectations author, then 53 years old, would die of natural causes five years to the day after the accident having avoided railroad travel as much as possible and confessing, “to this hour, I have sudden vague rushes of terror.”

Modern researchers have suggested he suffered from post-traumatic shock.

The Accident

Dickens, returning from a short holiday in France, was traveling in the train’s third car—a first-class carriage—with his mistress Ellen Ternan and her mother. At the time, work was being done on several bridges crossing the River Beult: The railway’s iron tracks had to be periodically taken up so any rotten wooden timbers below them could be replaced, and work on the 168-foot-long Staplehurst bridge was scheduled for June 9.

As the train approached the bridge at 50 mph, a signalman stationed 550 yards ahead of the work flagged the train to stop. The train’s engineer, an experienced man named George Crombie, immediately ordered the brakes applied and tried to reverse the locomotive’s engine to help stop the train. The work crew ran up the track waving their arms and shouting.

But it was all too late.

“Suddenly,” Dickens wrote, “we were off the rails and beating the ground as the car of a half-emptied balloon might do.”

The locomotive, its tender, and the first three cars of the train, including Dickens’s, jumped the 42-foot gap in the rails and landed on the far side, but Dickens’s carriage was being pulled backward by the car behind it and, he wrote [PDF], “hung in the air over the side of the broken bridge.” When the coupling at the rear of the car snapped, it sent all of the rest of the cars but two into the river.

The fall wasn’t far—the bridge was only 10 feet or so above the muddy water, and though the Beult ran high in the winter, it was quite low during the summer of 1865—but still, some of the wooden cars turned over and were flattened by their heavy iron undercarriages. “Windows and wooden panels were smashed so that deadly shards [had] sliced indiscriminately through the air burying themselves in whatever, or whoever, was in their way,” Dickens descendant Gerald Dickens wrote in his 2012 book, Charles Dickens and Staplehurst.

“No Imagination Can Conceive the Ruin”

According to his own account, Dickens had urged his traveling companions to be calm when the accident began, but by the time it was over, the crash had thrown the trio into a corner of the carriage. Dickens attended to Ellen and her mother—both of whom had received only minor injuries—as best he could before climbing out a window onto the bridge. He helped get people safely out of his car and then “got into the carriage again for my brandy flask, took off my travelling hat for a basin, climbed down the brickwork, and filled my hat with water.”

Amidst the wreckage, Dickens “came upon a staggering man covered with blood.” The author gave him water and helped him lie on the grass, where he soon died. Then, Dickens “stumbled over a lady lying on her back against a ... tree with blood streaming over her face” and gave her some brandy. When he next passed her, she, too, was dead. But some of the people he helped did survive, including a passenger who told a newspaper “he would have been strangled in a very few minutes if Mr. Dickens had not rescued him.”

Dickens continued helping until things quieted. Then, he remembered that the unfinished manuscript of his latest novel, Our Mutual Friend, had been left in the pocket of his coat, which was still on the train. He climbed across a plank back into the railway car to save the manuscript.

“No imagination can conceive the ruin of the carriages,” he later wrote, “or the extraordinary weights under which the people were lying, or the complications into which they were twisted up among iron and wood, and mud and water.”

The Aftermath

The deadly train crash would have made headlines no matter what, but Dickens’s presence, and the aid he offered his fellow passengers, was particularly newsworthy. (News he probably would have avoided if he could have; he was, after all, traveling with his mistress.)

“Mr. Charles Dickens had a narrow escape,” one newspaper article noted. “He was in the train, but, fortunately for himself and for the interests of literature, received no injuries whatever.” An eyewitness described seeing the author “running about with [his hat] and doing his best to revive and comfort every poor creature he met who had sustained serious injury.”

Questions as to the cause of the accident began immediately. At the time, trains from France to England were coordinated with high tides in the English Channel, which meant that train schedules varied day-to-day. Work crew chief Henry Benge had scheduled the Staplehurst work for a gap between trains, but he admitted at the scene that he had mistakenly looked at the journal’s Saturday schedule—which had the train arriving after 5 p.m.—when he should have looked at Friday’s, which would have showed that Dickens’s train was scheduled to arrive at 3:19 p.m.

Benge was charged, found guilty of negligence, and sentenced to nine months imprisonment. He never returned to railroad work.

The workman who had been sent up the track to flag down the train was also found to have inadvertently erred by posting himself too close to the work site. Regulations called for him to be 1000 yards away; he had measured his distance from the bridge by the number of telegraph poles he passed, but the poles near the bridge were later found to be unusually close together. He was not charged. Engineer Crombie was dismissed from his position.

In the immediate aftermath of the accident, Dickens appeared calm and collected, and in the five years of life remaining to him, he went on writing and giving readings, including on a trip to America. But he never got over the accident: He admitted that he was “quite shattered and broken up” and often made reference to the fact that the events had left him “shaken”; traveling became torture for him, something his children observed firsthand. “I have seen him sometimes in a railroad carriage when there was a slight jolt,” his son Henry Dickens wrote. “When this happened, he was almost in a state of panic and gripped the seat with both hands.” According to the author’s daughter, Mary “Mamie” Dickens, “my father’s nerves were never the same again” after the accident. She observed him on trains, trembling and sweating with terror, apparently with no awareness of anyone with him.

Then, she wrote, “he saw nothing for a time but that most awful scene.”