In 2019, the Hollywood press reported—with no small amount of incredulity—that James Dean was slated to star in a new movie. Dean, of course, has been dead since a car wreck claimed his life in 1955. But producers of Finding Jack insisted that a CGI version of Dean could be summoned to “play” the part of a Vietnam veteran, done with the full cooperation of the actor’s estate.

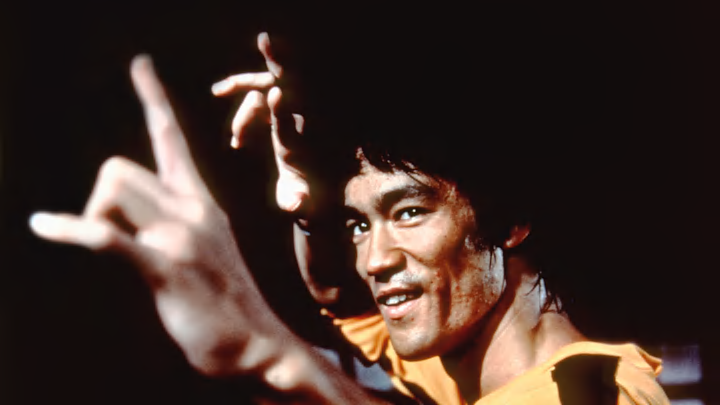

This movie necromancy made headlines, but the truth was that filmmakers had done it once before. In 1978, production company Golden Harvest released Game of Death, a kinetic martial arts movie starring the incomparable Bruce Lee.

That Lee had died five years earlier was simply another production challenge to be overcome.

The Dragon

Lee, who was born in San Francisco on November 27, 1940, was raised back in his parents’ native Hong Kong. A stint as a child actor and heavy dance training helped Lee become a highly physical performer with enormous stage presence. He returned to the U.S. in the 1950s to attend high school then went to college at the University of Washington. Later on, he taught his own Jeet Kune Do style of martial arts.

Lee’s charisma and balletic way of moving ended up being appealing to casting directors. He managed to land a number of television parts and eventually a co-starring role in the action series The Green Hornet (1966-1967), in which he played the title character’s sidekick, Kato.

But Lee’s ethnicity limited his opportunities. His idea for a TV series, Kung Fu, was handed to David Carradine. So Lee, disenchanted with Hollywood, returned to Hong Kong to make films like Fists of Fury and The Chinese Connection, which demonstrated his potential as a leading man. Hollywood took notice and offered him Enter the Dragon (1973), about a mysterious martial arts tournament on a private island. It became a monster hit, though Lee wouldn’t live to see its success.

Lee died at the age of 32 on July 20, 1973, just one month before Enter the Dragon was set to hit theaters. Though his exact cause of death remains the subject of speculation, it’s believed Lee suffered a cerebral edema, possibly as the result of heat stroke or a reaction to a painkiller he had ingested. (Lee had had the sweat glands in his armpits removed to avoid unsightly stains on his clothing while performing, leading some to believe he was sensitive to overheating.)

The runaway success of Enter the Dragon demonstrated the star Lee had become—but his success came too late for any film studio to capitalize on. This was especially galling to Golden Harvest, which had amassed some 40 to 100 minutes of footage for a movie titled Game of Death, which was both directed by and starring Lee. Filming ran from August to October of 1972, at which point the actor then halted production on that project to go film Enter the Dragon for Warner Bros. As the ’70s went on and interest in Lee grew, Raymond Chow, Lee’s former associate at Golden Harvest, began to think about how they might be able to squeeze one last starring role out of the late actor.

Resurrection

Game of Death was not particularly heavy on plot. Lee’s original premise was simply about a protagonist fighting his way to the top level of a building to retrieve a stolen treasure, and encountering various rivals along the way. It was something of a video game premise at a time when video games were only as sophisticated as Pong.

Golden Harvest was pleased to see that Lee had shot most of a face-off with towering NBA player Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. At 5 feet, 8 inches, Lee looked diminutive next to the 7 foot, 2 inch basketball star. The size difference made for a thrilling visual. So, too, did Lee’s wardrobe choice for the film: A bright yellow track suit later adopted by Quentin Tarantino for 2003’s Kill Bill.

The obvious issue was that the movie was only a fraction of what Lee had planned to shoot, with most completed scenes coming from the latter half of the film. To try and shape it into something coherent, Golden Harvest hired Robert Clouse, who had directed Lee in Enter the Dragon. Clouse reworked the plot so that Lee’s character, Billy Lo, is a performer up against a syndicate exploiting their talent. After faking his own death, he infiltrates their compound to exact revenge.

Many expenses were spared in order to complete Game of Death. To accomplish an illusion of Lee’s presence, Clouse shot Lee lookalikes—one who could act and one who could perform martial arts—and made sure the camera didn’t linger too long. The faux Lees were shot at angles, in favorable lighting, wearing fake beards, or even from behind to make sure the fact that it was a completely different actor it wasn’t too jarring. When the doubles proved impossible, Golden Harvest simply reused scenes from earlier Lee films. In one scene, Clouse resorted to shooting a cardboard cutout of Lee.

Actor Kim Tai-chung performed the martial arts sequences, which were supervised by Hong Kong stuntman Sammo Hung. (Chung also appeared as the “ghost” of Bruce Lee in 1986’s No Retreat, No Surrender with a then-unknown Jean-Claude Van Damme.) Yuen Biao appeared as Lee for dramatic scenes. Both were dubbed in English.

The most morbid choice made was a decision to feature footage from Lee’s actual funeral for a scene in which his character fakes his death. It was absurdly insensitive, but Golden Harvest seemed unafraid of any pending criticism. The allure of a Lee “comeback” film, post-mortem, seemed to render any questions of being in poor taste moot. (Lee's family was reportedly not consulted about the inclusion of this footage, but Lee's funeral services in both Hong Kong and Seattle were filmed as part of a documentary about his career.)

Game Over

Game of Death was completed, in the loosest sense of the word, in 1978. Roughly 12 minutes of the movie feature the real Lee, with the remaining 88 minutes relying on various sleight-of-hand tricks to disguise the legendary actor’s absence. The film was a box office hit, but enjoyment of it seems to depend on whether a viewer can accept it as a padded-out glimpse of what could have been or merely an exercise in exploitation no better than the parade of Lee lookalikes that peppered low-budget films for years afterward.

“While rivals constantly pretended to have discovered the ‘new’ Bruce Lee, whose appeal combined inimitable comic mugging and physical grace, characterized by explosive, incisive movements, Lee’s colleagues spent six years figuring out a way to integrate his last takes,” wrote The Washington Post’s Gary Arnold in 1979. “They might have inserted the completed sequences, which are self-contained routines anyway, in a feature-length biographical documentary. Instead they’ve cooked up a fiction designed to rationalize Lee’s curtain calls.”

The challenge originally facing the filmmakers behind Game of Death was not altogether unique. In 1937, producers of the film Saratoga had to finish shooting the picture even after star Jean Harlow died of kidney failure at age 26 before completing her role. Ridley Scott’s Gladiator (2000) coped with the passing of co-star Oliver Reed with CGI, as did 2015’s Furious 7 following the death of Paul Walker. Sadly, a similar set of circumstances befell 1994’s The Crow, which was completed following the on-set death of Bruce Lee’s own son, Brandon, after a gun was accidentally discharged.

In another tragic coda, Game of Death also marked the final film of Oscar-winning actor Gig Young, who filmed scenes with Clouse and Lee. On October 19, 1978, Young and his fifth wife, Kim—a German magazine editor whom he had met on the set of Game of Death—were found dead in their Manhattan apartment just three weeks after they married. Police ruled it a murder-suicide, though no motive was ever given.

In 2020, producer Alan Canvan utilized the remaining (and genuine) footage of Lee to edit Game of Death Redux, a 40-minute short film that attempts to realize Lee’s original vision for the movie. It was released as part of a box set from The Criterion Collection.

For Clouse, who died in 1997, his real legacy with Lee was Enter the Dragon. Of Game of Death, he offered little in the way of explanation aside from one admission: “I’m embarrassed by that movie.”