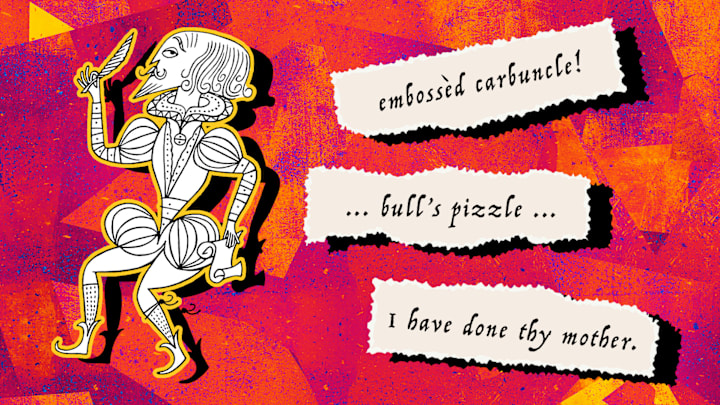

If there’s one thing William Shakespeare did best, it was making dirty jokes. Or coining words and phrases. Or using language so imaginatively that we’re still not always sure what he meant.

Or, as evidenced below, it might have been insults. Here’s a breakdown of 10 of the Bard’s best barbs, from an unfatherly outburst in King Lear to an iconic “your mom” moment in Titus Andronicus.

1. “Thou art a boil, a plague-sore or embossèd carbuncle in my corrupted blood.”

From: King Lear (Act 2, Scene 4)

King Lear: I prithee, daughter, do not make me mad.

I will not trouble thee, my child. Farewell.

We’ll no more meet, no more see one another.

But yet thou art my flesh, my blood, my daughter,

Or, rather, a disease that’s in my flesh,

Which I must needs call mine. Thou art a boil,

A plague-sore or embossèd carbuncle

In my corrupted blood. But I’ll not chide thee.

Let shame come when it will; I do not call it.

King Lear is supposed to be splitting his remaining time on Earth between the houses of his two eldest daughters, Goneril and Regan—but Lear’s 100 knights are lousy guests, and Goneril wants him to dismiss half of them. He storms off to plead his case to Regan, and the three characters end up in a bitter quarrel with the sisters united against their father.

Lear lists some ridiculous things he’d rather do than live at Goneril’s with just 50 knights (become a stablehand’s packhorse, for one), and when Goneril basically says, “Fine, do that,” Lear lets loose the impassioned outburst above. “Forget it. Goodbye forever, Goneril,” he’s saying. “You’ll always be my flesh and blood, and by that I mean you’re a bulging, festering abscess.” (His attempt to guilt her into relenting backfires, because when he says, “All my knights and I can just stay with Regan until you come to your senses,” Regan tells him he can only bring 25 knights.)

2. “ ... thou art false as hell.”

From: Othello (Act 4, Scene 2)

Othello: Why, what art thou?

Desdemona: Your wife, my lord, your true and loyal wife.

Othello: Come, swear it. Damn thyself,

Lest, being like one of heaven, the devils themselves

Should fear to seize thee. Therefore be double

damned.

Swear thou art honest.

Desdemona: Heaven doth truly know it.

Othello: Heaven truly knows that thou art false as hell.

Desdemona: To whom, my lord? With whom? How am I false?

Othello: Ah, Desdemona, away, away, away!

Othello confronts Desdemona (his wife) after becoming convinced that she’s having an affair with Cassio (his right-hand man). When she insists that heaven knows she’s virtuous, Othello’s retort is something to the effect of “The only thing heaven knows is that you’re hellishly deceitful.” Desdemona wasn’t cheating on Othello, which makes the insult hellishly cruel—but if you ever have incontrovertible proof that someone is deceiving you, “Thou art false as hell!” might pack a stronger punch than “You’re an evil liar!”

3. “ … you starveling, you elfskin, you dried neat’s tongue, you bull’s pizzle, you stockfish!”

From: Henry IV, Part 1 (Act 2, Scene 4)

Prince Hal: I’ll be no longer guilty of this sin. This sanguine

coward, this bed-presser, this horse-backbreaker,

this huge hill of flesh—

Falstaff: ’Sblood, you starveling, you elfskin, you

dried neat’s tongue, you bull’s pizzle, you stockfish!

O, for breath to utter what is like thee! You tailor’s

yard, you sheath, you bowcase, you vile standing

tuck—

Prince Hal: Well, breathe awhile, and then to it again, and

when thou hast tired thyself in base comparisons,

hear me speak but this.

Right before this verbal skirmish, Prince Hal and his pal Poins call out Sir John Falstaff for exaggerating his own feats during a robbery (in which, unbeknownst to Falstaff, the boys themselves had participated incognito). Hal, tired of all the braggadocio, pokes fun at Falstaff for his vast size, which Falstaff counters with a barrage of barbs related to Hal’s scrawniness.

He starts with a softball if there ever was one—starveling just means “starving person”—but finishes the sentence strong with a string of shriveled animal parts. A neat is a cow or an ox; a stockfish is any dried fish in the Gadidae family (which includes cod and haddock, among others); and a bull’s pizzle is a dried bull’s penis, once common as a flogging whip. Elfskin, meanwhile, is a bit of a mystery. It doesn’t appear anywhere else in the written record, and some people think Shakespeare actually meant eel-skin, which he used to describe skinny arms in King John.

Body-shaming comments are in poor taste, sure, but “You’re such a dried bull’s penis!” is a spectacular thing to shout at anyone, regardless of their size.

4. “ … a fellow … whose face is not worth sun-burning … ”

From: Henry V (Act 5, Scene 2)

King Henry: But, before God, Kate, I cannot look greenly nor gasp out my eloquence,

nor I have no cunning in protestation, only

downright oaths, which I never use till urged, nor

never break for urgin. If thou canst love a fellow of

this temper, Kate, whose face is not worth sun-burning,

that never looks in his glass for love of

anything he sees there, let thine eye be thy cook.

King Henry V (a.k.a. Prince Hal, all grown up) delivers this self-own while proposing to Princess Katherine of France during the play’s penultimate scene. As if calling his face “not worth sun-burning” didn’t already make it clear enough that he thinks he’s ugly, Hal follows it up with “I never look in the mirror just to admire my reflection.” Shakespeare didn’t make the character unattractive for no reason: The real-life Henry V took an arrow to the face during the Battle of Shrewsbury. Plus, it opens the door for Henry to make the point to Katherine that “a good heart,” unlike beauty, never fades.

5. “Thou hast no more brain than I have in mine elbows … ”

From: Troilus and Cressida (Act 2, Scene 1)

Thersites: [Achilles] would pound thee into shivers with his

fist as a sailor breaks a biscuit.

Ajax: You whoreson cur!

Thersites: Do, do.

Ajax: Thou stool for a witch!

Thersites: Ay, do, do, thou sodden-witted lord. Thou

hast no more brain than I have in mine elbows; an

asinego may tutor thee, thou scurvy-valiant ass.

Thou art here but to thrash Trojans, and thou art

bought and sold among those of any wit, like a

barbarian slave. If thou use to beat me, I will begin

at thy heel and tell what thou art by inches, thou

thing of no bowels, thou.

Ajax: You dog!

Thersites’s enslaver, the great Greek warrior Ajax, is trying to make him share what he knows about Trojan prince Hector’s challenge for one-on-one combat against Greece’s chosen champion. Instead of complying, Thersites pummels him with enough colorful insults to fill their own list. (To be fair, Ajax is pummeling him with blows.) He’s basically telling Ajax that he’s extremely stupid, and smarter men are just using him as a weapon—but he’s not even that good at fighting, especially compared to Achilles. In battle, Thersites says, “thou strikest as slow as another.”

“Thou hast no more brain than I have in mine elbows” is self-explanatory even to someone with an elbow’s amount of brain, and Thersites drives the point home by telling Ajax he’s so dim that a little donkey could teach him a thing or two.

6. “Methink’st thou art a general offense, and every man should beat thee.”

From: All’s Well That Ends Well (Act 2, Scene 3)

Lafew: Sirrah, your lord and master’s married. There’s

news for you: you have a new mistress.

Parolles: I most unfeignedly beseech your Lordship

to make some reservation of your wrongs. He is

my good lord; whom I serve above is my master.

Lafew: Who? God?

Parolles: Ay, sir.

Lafew: The devil it is that’s thy master. Why dost thou

garter up thy arms o’ this fashion? Dost make hose

of thy sleeves? Do other servants so? Thou wert

best set thy lower part where thy nose stands. By

mine honor, if I were but two hours younger, I’d

beat thee. Methink’st thou art a general offense,

and every man should beat thee. I think thou wast

created for men to breathe themselves upon thee.

Parolles: This is hard and undeserved measure, my

lord.

Lafew, an older French lord, reports that Parolles’s buddy Count Bertram has just gotten married, and Parolles balks at Lafew’s reference to Bertram as his “master” (it’s not the first time they’ve had this argument). Parolles is widely regarded as an untrustworthy blowhard, and Lafew is only too eager to drag him for sport.

“Methink’st thou art a general offense” is a pretty genteel way to say “You’re a honking problem to everyone,” but Lafew gets granular in his insults, too. “I think thou wast created for men to breathe themselves upon thee” means something like “You were made to be a punching bag.” Lafew also tells Parolles that his sleeves look like leggings. Parolles’s response to all the slander, in modern parlance? “I don’t deserve this sh*t.”

7. “ … your beards deserve not so honorable a grave as to stuff a botcher’s cushion or to be entombed in an ass’s packsaddle.”

From: Coriolanus (Act 2, Scene 1)

Menenius: Our very priests must become mockers if

they shall encounter such ridiculous subjects as

you are. When you speak best unto the purpose, it

is not worth the wagging of your beards, and your

beards deserve not so honorable a grave as to

stuff a botcher’s cushion or to be entombed in an

ass’s packsaddle. Yet you must be saying Martius is

proud, who, in a cheap estimation, is worth all

your predecessors since Deucalion, though peradventure

some of the best of ’em were hereditary

hangmen. Good e’en to your Worships. More of

your conversation would infect my brain, being

the herdsmen of the beastly plebeians. I will be

bold to take my leave of you.

Roman patrician Menenius is lambasting the two tribunes (commoners’ elected officials) Sicinius and Brutus for being really bad at their job. He accuses them of having become politicians just for attention and criticizes them for wasting all their time on trivial matters. Whenever they do speak up about something more significant, Menenius says, their thoughts are “not worth the wagging of their beards”; in other words, it’s not worth the energy it took to utter them aloud. Speaking of beards, theirs don’t even deserve to become stuffing for pincushions or packsaddles—a truly inspired way to say “You guys are completely worthless.”

8. “Away, thou issue of a mangy dog!”

From: Timon of Athens (Act 4, Scene 3)

Apemantus: Thou art the cap of all the fools alive.

Timon: Would thou wert clean enough to spit upon!

Apemantus: A plague on thee! Thou art too bad to curse.

Timon: All villains that do stand by thee are pure.

Apemantus: There is no leprosy but what thou speak’st.

Timon: If I name thee.

I’ll beat thee, but I should infect my hands.

Apemantus: I would my tongue could rot them off!

Timon: Away, thou issue of a mangy dog!

Choler does kill me that thou art alive.

I swoon to see thee.

Timon of Athens, rendered destitute by his own recklessly irresponsible largesse, has withdrawn to the wilderness after his friends declined to bail him out of his predicament. He’s in full misanthrope mode when the philosopher Apemantus pays him a visit, and the two mostly spend it complaining about how annoying they find each other.

Apemantus is articulate, but Timon probably deserves the title for most cutting one-liners—notably, “Would thou wert clean enough to spit upon!” (i.e. “If only you were clean enough to spit on!”). “Away, thou issue of a mangy dog!”, meanwhile, is Timon’s version of “Go away, you son of a bitch!” (a dirty one, at that). Pretty rich coming from someone who lives in a cave.

9. “I wonder that you will still be talking … nobody marks you.”

From: Much Ado About Nothing (Act 1, Scene 1)

Beatrice: I wonder that you will still be talking, Signior

Benedick, nobody marks you.

Benedick: What, my dear Lady Disdain! Are you yet

living?

Beatrice: Is it possible disdain should die when she

hath such meet food to feed it as Signior Benedick?

Courtesy itself must convert to disdain if you come

in her presence.

Benedick: Then is courtesy a turncoat. But it is certain

I am loved of all ladies, only you excepted; and

I would I could find in my heart that I had not a

hard heart, for truly I love none.

Beatrice: A dear happiness to women. They would

else have been troubled with a pernicious suitor.

Beatrice, niece of Messina’s Governor Leonato, and Benedick, a gentleman soldier from Padua, are masters of the flirtatious roast. Leonato describes their dynamic as “a kind of merry war” and “a skirmish of wit.” It’s on full display in their first sparring match (in the play), which Beatrice kickstarts by saying “I can’t believe you’re still talking—nobody’s listening.” Benedick then expresses surprise that “Lady Disdain” is still alive, and Beatrice parries with “How could she die when she has you to feast on?” It gets even better from there, and Benedick manages a mic drop (though Beatrice doesn’t think much of him for ending the exchange prematurely).

10. “Villain, I have done thy mother.”

From: Titus Andronicus (Act 4, Scene 2)

Demetrius: Villain, what hast thou done?

Aaron: That which thou canst not undo.

Chiron: Thou hast undone our mother.

Aaron: Villain, I have done thy mother.

Demetrius and Chiron are reacting to the news that their mother, Empress Tamora, has just given birth to a Black baby—making it obvious that the father isn’t her husband, Emperor Saturninus of Rome, but her Black lover, Aaron. In an especially bleak and violent story, the exchange between the three men is a welcome moment of comic relief made even funnier by the fact that Aaron isn’t actually joking: He really has done their mother.