Everyone’s heard about books becoming films, but what about films that became books? Also known as movie novelizations, these works let fans dive deeper into the world of their favorite flicks and often offer a little more context and characterization than one might get on-screen.

They began to pop up about a century ago, with some silent films (like 1927’s London After Midnight) getting the screen-to-page treatment. In 1932, King Kong became one of the first talkies to get turned into a book. The industry progressed and hit its peak by the late ‘70s, when the global success of franchises like Star Wars meant millions of readers for their associated books. Throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s, movies like Clue, Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, and the Taming Of The Shrew-inspired 10 Things I Hate About You got the tie-in treatment, too.

According to GoodReads, more than 320 movie novelizations have been published to date, with authors like Todd Strasser, Alan Dean Foster, and David Levithan pumping out dozens throughout their collective careers. (Interestingly, Levithan also co-wrote two books that turned into Hollywood movies: Nick & Norah’s Infinite Playlist and Naomi and Ely’s No Kiss List.) Some works are flimsy kiddie fare, but others have drawn much acclaim, selling millions of copies and becoming essential to the film canon that spawned them.

The screen-to-page industry has petered off a bit since its heyday, but some popular movies occasionally still merit an accompanying novelization. (There’s one of The Room, for instance.) Here’s our list of seven movie novelizations worth reading.

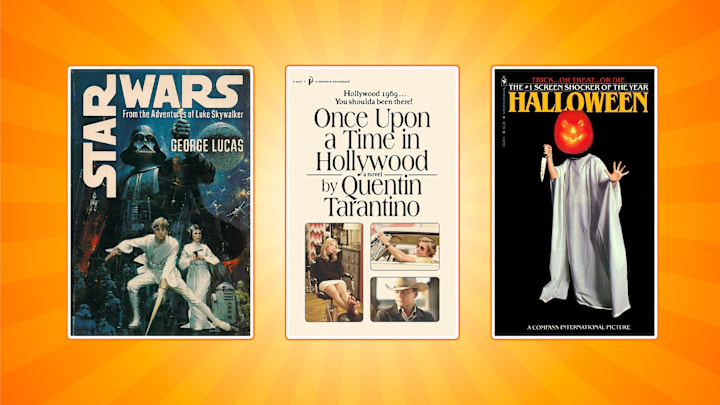

- Star Wars: From the Adventures of Luke Skywalker // Alan Dean Foster (credited to George Lucas, 1976)

- Halloween // Curtis Richards (1979)

- Alien // Alan Dean Foster (1979)

- 2001: A Space Odyssey // Arthur C. Clarke (1968)

- Back To The Future // George Gipe (1986)

- Road To Perdition // Max Allan Collins (2002)

- Once Upon A Time In Hollywood // Quentin Tarantino (2021)

Star Wars: From the Adventures of Luke Skywalker // Alan Dean Foster (credited to George Lucas, 1976)

Though initially credited to George Lucas, this Star Wars novelization was actually ghostwritten by sci-fi icon Alan Dean Foster, who wrote it based off the film’s shooting script and Xerox copies of artist Ralph McQuarrie’s pre-production paintings. Foster also spent a day in an Industrial Light And Magic screening room with Lucas and graphic designer Saul Bass, watching unedited, soundless footage of Tie Fighters zooming around and getting blown up.

From the Adventures of Luke Skywalker was published six months before the movie came out in May 1977, and it was panned by critics—but audiences loved it, and the book sold through its initial 500,000-print run by February, still three months before the film’s premiere. By the time the movie came out, another 3.5 million copies had been sold, making it one of the most successful novelizations of all time. (Foster was paid $7500 for the work—worth about $40,000 today—but also negotiated a 0.5 percent sales royalty with Lucas. He was receiving annual payouts for years until Disney acquired Star Wars and withheld royalties, resulting in a lawsuit in 2020.)

The novelization hits all the movie’s high points, but there are some fascinating differences (a lightsaber is described as a “gizmo” with “a number of jewel-like components built into both the handle and the disk,” for example) that give it a different type of feel from the film. It all adds more to the Star Wars universe, and some of details about certain planets, languages, history, and technology have since become canon for fans.

Halloween // Curtis Richards (1979)

A novelization so beloved that it spawned a commemorative re-release in 2023, Curtis Richards’s Halloween hit shelves on October 1, 1979, almost one year after the film dropped in theaters. Telling the story of “the most frightening night of the year,” the novelization extends John Carpenter’s script and combines it, somewhat, with the events that would come in 1981’s Halloween II. (That movie still got its own novelization, though, as did Halloween III.) There’s a richer backstory in this for Michael Myers, with an opening that suggests he carries an ancient Druid curse cast that stems from Northern Ireland. Readers also get to experience some of Michael’s perspective along the way, so some might feel a bit more empathy for him—even if he is a knife-wielding maniac.

Alien // Alan Dean Foster (1979)

Star Wars wasn’t the only sci-fi fandom that Foster touched. He also worked on the novelization of 1979’s Alien, where he clashed with studio executives at 20th Century Fox. They were so concerned with security that they wouldn’t even show Foster pictures of the film’s titular extraterrestrial, meaning the author had to pen the entire book without even knowing what a Xenomorph looked like. He managed to pull it off, though, and went on to write not only a series of celebrated Star Trek novelizations, plus tie-ins for Clash Of The Titans, The Thing, and Terminator Salvation, among many others.

2001: A Space Odyssey // Arthur C. Clarke (1968)

Arthur C. Clarke’s 2001: A Space Odyssey is a novelization in the sense that it was developed in tandem with Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film of the same name. But the book, released three months after the film’s premiere, was based in part on a number of short stories by the author, including 1953’s “Encounter In The Dawn.” Though Kubrick and Clarke worked on the book together and Clarke got co-screenwriting credit on the movie, only Clarke received author credit for the book, something that must have felt great, considering the work has gone on to sell more than 3 million copies worldwide.

While some people, like Hugo Award-winning author James Blish, felt that Clarke’s text had “little of the poetry of the picture,” others like New York Times book reviewer Eliot Fremont Smith called it “a fantasy by a master who is as deft at generating accelerating, almost painful suspense as he is knowledgeable and accurate (and fascinating) about the technical and human details of space flight and exploration.” Clarke would go on to write an entire Space Odyssey series, four novels in total, released over the course of 20 years and spanning our entire solar system.

Back To The Future // George Gipe (1986)

First conceived by writing partners Bob Gale and Robert Zemeckis in 1980, Back To The Future was famously passed on more than 40 times by various studios and producers before Universal Studios snagged it following Zemeckis’s success directing 1984’s Romancing The Stone. The movie would end up a worldwide smash, grossing $388 million dollars—more than 20 times its $19 million budget—spawning two successful sequels, and earning Gale and Zemeckis Academy Award nominations for Best Screenplay.

It’s a little surprising that Gale, who Michael J. Fox has called “the gatekeeper of the franchise,” let someone else take on the movie’s novelization. But he did, and he handed the reins over to George Gipe (Parts II and III were penned by Craig Shaw Gardner). Gale would step back into the film’s literary world decades later, though, writing plot outlines for five different BTTF novelizations released by IDW Publishing starting in 2015, including Back To The Future Vol. 2, Back To The Future: Citizen Brown, and Back To The Future: Biff To The Future.

Road To Perdition // Max Allan Collins (2002)

When Max Allan Collins first wrote the graphic novel Road To Perdition in 1998, he couldn’t have known it would be made into a movie about four years later. Collins had written a several books before—including a number of original mystery series, plus novelizations of the films Maverick, Air Force One, Waterworld, Dick Tracy, and In The Line Of Fire, the latter of which he had to write in just nine days—but Road To Perdition was his first work to be adapted for the silver screen, save a couple of low-budget horror movies. (The charmingly named Mommy and Mommy 2: Mommy’s Day, shot in his Iowa hometown.)

Because Collins was an established author who knew the novelization game, it only made sense then that he was asked to write the novelization of his own work. However, because the novelization was meant to be based on the movie, that meant he had to work off the film’s shooting script and character development, rather than what he’d originally penned in his novel. “I couldn’t write anything about the characters that I had created,” he told Vanity Fair in 2014. Calling it “one of the great frustrations” of his career, Collins said he turned in a 90,000-word novelization that fleshed out the film and merged it with the original graphic novel, only to have it cut down to 40,000 words, all specifically angled toward the movie.

Once Upon A Time In Hollywood // Quentin Tarantino (2021)

Every single film Quentin Tarantino has directed, from 1992’s Reservoir Dogs to 2019’s Once Upon A Time In Hollywood, has been based on a script written by the director himself. (He also penned the scripts for Tony Scott’s True Romance and Robert Rodriguez’s From Dusk Till Dawn.) And yet, it wasn’t until the release of Once Upon A Time that Tarantino decided to step into the publishing world, inspired by the role movie novelizations had on his life as a young cinema lover.

His first release, a 2021 novelization of Once Upon A Time In Hollywood, follows the career arc of fictional action star Rick Dalton, played by Leonardo DiCaprio in the film. Cliff Booth, the friend and stunt double played by Brad Pitt, is there too, and in greater detail than in the movie, with brand new plot lines and backstory. There are bits about Charles Manson’s pursuit of a music career and the nightly “creepy crawls” by members of his notorious “family,” wherein they’d break into wealthy family homes while they slept. Also, there are chapters about the Western series Lancer and its lead actor, James Stacy, with a look inside the head of Dalton’s Lancer co-star, the young Trudi Fraser.

Throughout the novelization, Tarantino peppers in his thoughts about movies and TV shows of the era and adds even more real-life figures to the story, including NFL star Jim Brown, record producer Terry Melcher, and actress Candice Bergen, all of whom become characters in Tarantino’s larger universe. It all seems to have worked, too: The book debuted at No. 1 on The New York Times fiction best-seller list, and Tarantino won the “Writer Of The Year” award for it from GQ in 2021.

Discover More Fascinating Facts About the Best—and Worst—Book Adaptations: