In a way, Theresa Small hoped the news wasn’t true. It was summer 1921, and her husband, Ambrose Small, had been missing for nearly two years. A man of means, wealth, and influence who was known across Canada, his disappearance had made for sensational headlines.

Now, two men from all the way in Des Moines, Iowa, claimed that they had found Small. But whatever had happened to the man in the interim had been tragic: He was missing both legs, nearly catatonic, and able to utter only four words: train, from Omaha, and a name, Doughty.

While Theresa waited for confirmation, she must have been torn between wanting the mystery to end and not wishing to believe her husband had met such a fate. The entire situation seemed drawn from a thriller novel: In late 1919, Small had accepted a check for the impressive sum of $1 million—nearly $18 million today—after selling off much of his business empire. Then, only hours later, he had vanished without a trace, the money untouched.

It was inexplicable. Then again, so was Theresa’s seeming reluctance to report him missing until weeks had passed. And so were attempts to locate Small via the use of telepathy, along with reports of secret lairs, cryptic messages, and kidnapping plots by his employees. Even Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, famed creator of Sherlock Holmes, was dragged into the proceedings. In Ambrose Small, Canada found its most gripping true-crime case of the 1920s. Perhaps it would come to an end in Des Moines.

So Theresa Small did what she could. She sat by the phone and waited to hear what else the legless man had to say.

A Flair for the Dramatic

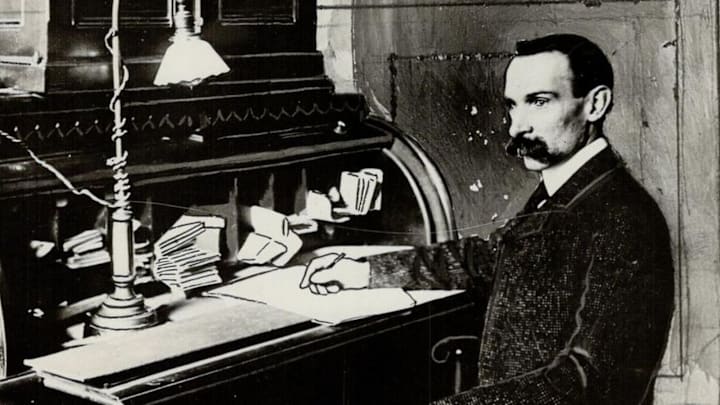

Ambrose Small was no futurist, no innovator, no revolutionary. He was simply possessed of a

mind for business, specifically the ownership and operation of theaters throughout Ontario. Small’s venues were home to stage performances of all kinds. If you sought out some kind of live entertainment in the region, you were almost inevitably going to step into a Small-run property and perhaps even run into the man himself, a slightly-built, middle-aged entrepreneur with a bushy mustache and a piercing stare.

Small’s empire began modestly, when he was an usher at the Grand Opera House in Toronto. Feeling there was little opportunity for advancement there and at odds with his supervisor, he departed for the Toronto Opera House, was soon appointed manager, and became successful enough to buy the Grand Opera House outright. (Predictably, his ex-boss was an early casualty of the new Small regime.)

By 1919, Small’s holdings had grown to more than 30 locations in Ontario, and he controlled bookings for dozens more. While it was an impressive feat, Small realized that live performances were likely to give ground to the increasing number of movie houses dotting North America. Worse, the 1918 flu had forced theater closings. Now seemed like the best time to find an exit. He soon entered into a deal with a company dubbed Trans-Canada Theaters Limited. For the sum of $1.7 million, or nearly $30 million today, Small agreed to sell off all of his theaters. It was perhaps a concession to the evolving entertainment world—but at 53, it was also a reward for all of Small’s efforts.

On December 2, 1919, Small and his wife Theresa left their home in Toronto. The two went to tend to separate affairs before reconvening with his lawyer, E.W.M. Flock, at Small’s Grand Opera House office. Trans-Canada had remitted a check for $1 million a day earlier, which Small deposited at his bank. Later, he and Theresa headed to an orphanage where she volunteered. As they parted ways, Small said he would see her back home for dinner at 6 p.m.

Small then returned to his office to confer with Flock again. This session lasted until roughly 5:30 p.m.

Small was due home in just 30 minutes. He never arrived.

Most people would be alarmed by the absence of their spouse, but Theresa was not. She knew her husband wasn’t faithful in their marriage, and the most probable explanation for his failing to show up was because he was carrying on with another woman. Likely embarrassed, she kept quiet.

But other people took notice of Small’s disappearance. As the days turned into weeks, local newspapers began running stories. Among those queried was George Driscoli, an executive with Trans-Canada who had dealt with Small in the theater acquisition. Driscoli appeared unperturbed.

“It is just three weeks ago today since Mr. Small was here to close up the deal by which we took over all his theatrical interests,” Driscoli said. “At that time he told me that it was his intention to take a long rest. He had been working hard, and relieved of the strain of his extensive interests, he thought it was a good time to take a vacation, which he intended to spend somewhere entirely out of touch with the theatre and his other affairs.” Driscoli guessed he was out in the woods somewhere, or possibly in Europe.

Other outlets claimed Theresa said her husband was suffering from a nervous breakdown and was merely resting. In truth, Theresa had no apparent idea of where he was. And that was ultimately enough for James Cowan, manager of the Grand Opera House, to reach out to police. A detective named Austin Mitchell was assigned to the case. It would be among the strangest he would ever work on.

Bonded

Mitchell attempted to try and place Small somewhere—anywhere—else besides the meeting with Flock the evening of December 2. Two newspaper delivery boys claimed they had spotted Small. Another eyewitness said Small entered a hotel near the Grand Opera House. But Mitchell found that they couldn’t be exactly sure whether it was December 2 or the night before. Another insisted he saw four men struggle to bury something heavy in a dump near a ravine. Nothing was ever recovered.

Still, it wasn’t a stretch to believe Small had run afoul of someone. In addition to his sharp business mind, he also had a head for gambling, possibly horse race fixing, as well as womanizing—he was even reputed to have a “hidden” room in the Grand Opera House for liaisons with actresses and dancers. Any or all of these activities could have motivated someone to harm Small, whether it was a jilted spouse or someone involved in illicit activity.

That notion was strengthened when Mitchell discovered a wire message sent from Ontario to New York that read simply: “Hold Small until tomorrow morning.” It was easy to infer a kidnapping plot was afoot. But Mitchell turned up nothing else.

Mitchell also knew of a second disappearance that was almost certainly connected to the Small case. A month after Small dropped out of sight, an employee of his, John Doughty, skipped town. Mitchell discovered that Doughty had taken $105,000 in bonds belonging to Small with him. Even more suspicious: Doughty had removed the bonds from the bank the morning of Small’s disappearance.

A $15,000 reward was offered for information leading to Doughty’s capture. In late 1920, he was spotted working at a paper mill in Oregon under the alias Charles Cooper. The bonds were in the home of Doughty’s sister. Doughty told authorities that Small had asked him to take the bonds out of the safety deposit box at his bank and hold them. After that, Doughty said, Small vanished.

Pressed for information about Small, Doughty offered a curious response. “I would like to help you,” he said. “You have treated me well, but I have been advised by my counsel not to discuss the case.”

Mitchell found that Doughty had discussed the idea of kidnapping Small with two co-workers. While all this seemed promising, it was paltry evidence for court. No evidence of a kidnapping was forthcoming. As for the bonds: Doughty argued he had power of attorney, and as such his removal of the bonds wasn’t actually theft. He fled town, he said, because the fact he had the bonds meant he would be a suspect in Small’s disappearance.

A jury found him guilty of theft but not of any kidnapping plot, a charge which was never brought by prosecutors to trial. He was sentenced to six years in prison.

With Doughty unwilling or unable to furnish any more information, the case continued to unravel. Once, a reporter took Small’s file and practically shoved it into the hands of Sherlock Holmes author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, believing the creator of Holmes might somehow crack the case. Doyle was obliging but had no real intention of exploring it.

Small sightings were also in abundance. Blackstone, a famous magician, swore he saw Small gambling in Mexico after he had gone missing. But it was not until the Des Moines call in August 1921 that Theresa thought there might be real hope her husband had been found.

Most of him, anyway.

A Leg Up

Frank Harty and John Brophy were once police officers in Des Moines. Now they were private detectives, and they had an incredible tale to tell.

Under their care was a man without legs and only a handful of words at his disposal. The man, they insisted, was Ambrose Small. They knew this because he looked remarkably like the photos of Small that were plastered in newspapers. More than that, he uttered what sounded like “Doughty” when they asked him his name. It seemed to be a reference to John Doughty, the highly suspicious employee who had taken the bonds.

Mitchell and other authorities were keen on getting a glimpse of the man. Theresa was contacted and told there was a chance this could be Small—a mangled version of him, but Small nonetheless.

That hope expired rapidly. The man was not Ambrose Small but Charles Daughtery, a transient whose legs had been badly injured when he hopped off a train. When the private detectives asked him his name, he responded correctly. The problem was that Daughtery sounded a lot like Doughty. At 33, he was also some two decades younger than Small.

Whether the men genuinely believed him to be Small or simply hoping he could be passed off as such to claim a $50,000 reward is unknown. Either way, it was yet another blow to Mitchell and to Theresa. In addition to losing her husband, her inheritance was also being challenged by Small’s sisters, Gertrude and Florence. (It was ultimately resolved in Theresa’s favor, though the Small estate never received the $700,000 outstanding from Trans-Canada, which went out of business.)

No Small Discovery

The absence of real evidence allowed for Small’s case to attract a stream of crackpots. In 1928, a Vienna criminologist named Maximilian Langsner claimed a combination of “mental telepathy and thought analysis” would allow him to resolve the mystery and present Small’s skeleton. At one point, he aroused the interest of the Small sisters and planned on excavating the dump where an eyewitness had reported seeing something being buried. Ultimately, Langsner failed to provide any special knowledge of the case.

In 1930, Small’s longtime barber, Arthur Weatherup, insisted that the body of a person with amnesia who had died in hospital care was that of Ambrose Small. Police quickly threw cold water on the idea. Sixteen years later, the original site of the Grand Opera House was excavated, and some believed the building might harbor a secret, including a body. Again, nothing was uncovered.

Read More Articles About Historical Mysteries:

Small’s disappearance became a kind of shorthand in Canada. If someone was digging a hole, they might be asked if they were looking for him. The one man who might have a real answer, John Doughty, died in 1949 having offered no additional detail about what—if anything—he knew about it, though the fact he took $105,000 of Small’s money the day Small vanished is a hard coincidence to believe.

After getting out of prison, Doughty said little. “As far as my past is concerned, it is a closed book,” he insisted. “I have nothing to say about Mr. Small, or anything connected with him.”

The delay in reporting Small missing didn’t help, either, something the Small sisters likely held against Theresa. Upon her death in 1935, Gertrude and Florence produced a note they insisted was Theresa’s confession to the murder of her husband. According to the letter, Small’s body was said to have been burned up in a furnace, with the remains buried in the dump. Conveniently, that would mean the two would inherit her estate instead of the money going to charity. A judge tossed the confession out of court, declaring it a forgery.

That Small would simply abandon his comfortable life, complete with a full bank account, remains puzzling—and given the complete lack of any credible leads as to his whereabouts, it seems likely he came to a violent end. As a purveyor of stage plays, it’s morbidly fitting that Small had the most memorable curtain call of them all.