Pompeii is one of the most famous ancient cities in the world, thanks to its preservation by a thick layer of volcanic mud after the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE. Its many streets and buildings are still being excavated by archaeologists and offer an unprecedented glimpse into life in the Roman Empire. Below are 14 facts about Pompeii.

- Pompeii was settled in the 8th century BCE.

- Pompeii’s citizens enjoyed a high standard of living.

- The eruption of Vesuvius buried Pompeii and nearby Herculaneum in ash.

- Pliny the Younger was an eyewitness to the disaster.

- The exact location of Pompeii was unknown for hundreds of years.

- Workers at the earliest excavation ran off with artifacts they found.

- DNA analysis overturned an assumption about some of Pompeii’s victims.

- Ordinary homes and businesses reveal details of everyday life in Pompeii.

- Gladiators trained and fought in Pompeii.

- Pompeii’s citizens gathered at luxurious thermal baths.

- Archaeologists have discovered 50 carbonized loaves of bread.

- Artists used a special technique to paint Pompeii’s colorful frescoes.

- Only two-thirds of Pompeii has been excavated so far.

- You can walk in the footsteps of Pompeii’s citizens.

Pompeii was settled in the 8th century BCE.

Pompeii is situated about 14 miles southeast of Naples in the Campania region of southern Italy. The settlement was built on fertile lava terraces at the bottom of Mount Vesuvius, near the mouth of the Sarnus River, and was first inhabited around the 8th century BCE by prehistoric peoples called the Oscans. Pompeii later came under the influence of a multitude of local cultures, from Greek to Etruscan, ensuring the city would be a melting pot. By the 5th century BCE, a group known as the Samnites grew Pompeii into a prosperous city, which attracted the attention of the Romans, who fought several wars in an attempt to gain control.

History books mention the city for the first time in 310 BCE when Romans attacked it for the second time, but it was not until 80 BCE that the people of Pompeii became Roman citizens. This vibrant, dynamic cultural history is still reflected in the buildings and archaeology of Pompeii.

Pompeii’s citizens enjoyed a high standard of living.

Pompeii had a lot of things going for it. Its location on the Italian peninsula’s coast made it an important stop on maritime trade routes, while the rich soils surrounding the city supported thriving agriculture. Both allowed the city to flourish economically and swell to a population of 20,000.

As its citizens’ wealth grew, Pompeii’s middle classes—made up of merchants and business people— enjoyed a better standard of living than that in nearby settlements. They displayed their good fortune by building impressive villas and supporting public infrastructure like grand avenues, a forum, an amphitheater, and numerous temples, all adding to the city’s opulence.

The eruption of Vesuvius buried Pompeii and nearby Herculaneum in ash.

Unfortunately, Pompeii’s location where the African and Eurasian tectonic plates meet also make it prone to earthquakes and volcanoes. In 62 CE, a powerful earthquake tore through the region, damaging many buildings and disrupting the comfortable lives of the inhabitants.

The city had barely recovered from the disaster when, probably on August 24, 79 CE, the catastrophic eruption of Mount Vesuvius shot a 10-mile-wide plume of ash into the sky. Pumice, mud, and volcanic debris rained down on Pompeii for the next 12 hours. Thousands fled while about 2000 people took shelter in Pompeii’s buildings. Those who survived the initial onslaught of ash and rocks were killed the next day when a toxic cloud of gas enveloped Pompeii.

The neighboring city of Herculaneum had been protected from the worst of the eruption by a westerly wind, but when it changed direction, the deadly gas blew through the town and killed everyone. The final devastating blow came as rock and mud cascaded over Pompeii and Herculaneum and buried the two cities under 19 to 25 feet of volcanic muck for centuries.

Pliny the Younger was an eyewitness to the disaster.

A lot of what we know about the volcanic eruption of Vesuvius comes from two letters written by Pliny the Younger to the Roman historian Tacitus. Pliny the Younger was just 17 and staying with his mother in a village to the east of Vesuvius. In one letter he reported that his uncle, Pliny the Elder, commander of the Roman fleet in the Bay of Naples, had sailed towards Pompeii to see if he could help the citizens there. As he stepped ashore to rescue the fleeing people, he was overcome by toxic gas and died.

In the second letter, Pliny the Younger wrote that he and his mother escaped from from their villa as the volcano erupted: “We saw the sea sucked back, apparently by an earthquake, and many sea creatures were left stranded on the dry sand. From the other direction over the land, a dreadful black cloud was torn by gushing flames and great tongues of fire like much-magnified lightning.” He heard people screaming and crying as the darkness closed in. The next day when the light broke through, “we were amazed by what we saw, because everything had changed and was buried deep in ash like snow,” he wrote.

The exact location of Pompeii was unknown for hundreds of years.

Pompeii remained undisturbed in its ashen cocoon for around 1500 years. The first hints that something exciting was underfoot came in 1592, when an architect building a subterranean aqueduct came across a buried building with frescoes on the wall. Further single buildings were unearthed in 1689 and 1693, but because Pompeii had lain buried for so long, there was no surviving knowledge of exactly where the city was situated.

No large area of Pompeii was found until 1748 during attempts to excavate the ancient city of Stabiae, also set on the Bay of Naples. However, as digging progressed, an inscription conclusively identified the site as Pompeii.

Workers at the earliest excavation ran off with artifacts they found.

At the time of Pompeii’s first excavations, archaeology was not yet a developed science with accepted standards and methodologies. The digs were haphazard, and some workers even looted the site. It was not until the 1860s that a proper archaeologist, Giuseppe Fiorelli, began a systematic exploration of the site. He divided the city into nine regions, numbered every block, and gave the door of every house a number, allowing the city to be mapped. Most famously, Fiorelli also developed a technique to pour cement into the negative spaces in the ash left by decomposed bodies, creating casts of the fallen citizens of Pompeii and providing some of the most iconic artifacts of the disaster.

DNA analysis overturned an assumption about some of Pompeii’s victims.

One of the most famous casts from Pompeii was taken in the villa known as the “House of the Golden Bracelet”—so named because a beautiful gold bracelet featuring a coin held between two snake heads was found there.

During the eruption, two adults and two children took shelter under a staircase in the lavishly decorated, three-story villa. The shower of mud and ash caused the staircase to collapse, killing all four. Archaeologists assumed that the quartet was a father, mother, and their two children—but in November 2024, a study in the journal Current Biology revealed a different story. DNA analysis from the plaster casts showed that all four people were male and none was related to each other, raising puzzling questions over who they were and why they died together.

Ordinary homes and businesses reveal details of everyday life in Pompeii.

Pompeii’s city walls had a 2-mile circumference and encircled streets packed with houses, villas, shops, temples, and public spaces. While public buildings such as the forum, bath houses, and amphitheater are all impressive, the hundreds of ordinary homes and shops reveal a wealth of details about life in the Roman Empire. “The House of the Surgeon,” found with medical instruments on its floor, is one of the oldest houses in Pompeii and was likely built in the 2nd century BCE out of large limestone blocks in a simple atrium form. The city was famous for its cloth; the “House and Workshop of Verecundus” represents a typical cloth-making and dyeing workshop. Frescoes on the walls of the workshop not only depict the work of cloth-makers but also the gods Mercury and Venus, thought to be the protectors of this profession.

In 2023, archaeologists reported the discovery of a private bakery operated by enslaved people who were forced to grind grain for the inhabitants of the connected villa. Slavery was common in the Roman Empire, and evidence at Pompeii continues to bring the lives of enslaved people, often hidden in the historical record, to light.

Gladiators trained and fought in Pompeii.

There is plenty of evidence of gladiators in Pompeii. Archaeologists have identified the remains of barracks where they lived and a gymnasium where they trained before their fights at the amphitheater, and even found graffiti recording the gladiators’ wins (successful fighters were regarded as heartthrobs). Children’s drawings in one house appear to show gladiatorial battles, and bright frescoes likely painted on the walls of a tavern depict two styles of gladiator, a murmillo and a thraex.

Pompeii’s citizens gathered at luxurious thermal baths.

Bath houses were important social gathering spaces in Pompeii, drawing citizens from all social strata for hygiene and gossip (because only the wealthiest citizens could afford their own private bathing facilities). Several thermal baths have been excavated in Pompeii, revealing a great deal about how these spaces were used. Most baths included latrines, a pool, and sometimes a garden or gymnasium. Each interior room had a specific functions. Men and women had a gender-segregated apodyterium (changing room), frigidarium (cold-water bath), tepidarium (lukewarm bath), and calidarium (hot-water bath). The rooms were heated using a clever system of hot water pumped through cavities in the walls.

The earthquake of 62 CE damaged most of the bath houses in Pompeii, and only one, the Forum Thermal Baths, continued to be used after the earthquake.

Archaeologists have discovered 50 carbonized loaves of bread.

One of the many valuable insights into ordinary life in Pompeii comes from the wide variety of food and drink depicted not only in frescoes and mosaics, but also as carbonized remains: Vesuvius’s intense heat turned many items into charcoal. In a bakery, more than 50 round loaves of whole-meal bread were discovered—some still in the oven—indicating that bread was a staple Roman foodstuff. Remains of seeds and fruits suggest a Roman diet rich in almonds, figs, olives, dates, lentils, and beans. Archaeologists have also found a glirarium, a special pot used by Romans to fatten up one of their favorite delicacies: edible dormice.

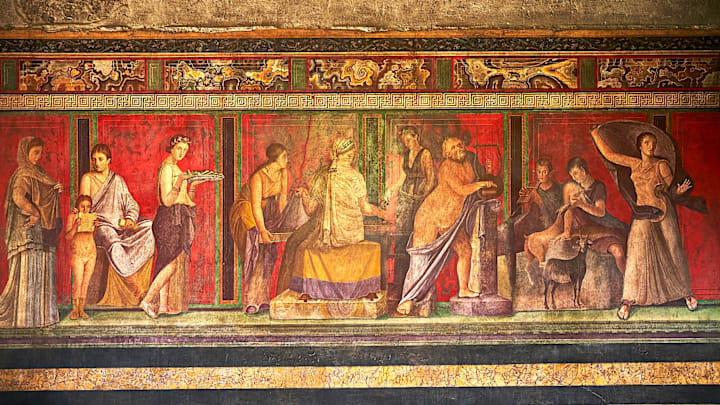

Artists used a special technique to paint Pompeii’s colorful frescoes.

Still-vibrant frescoes adorn the walls of many of the villas. The artwork has retained much of its original color due to the technique of applying a coat of limestone plaster to a wall and then painting the designs while it was still wet, ensuring the pigments were sealed into the walls as the plaster dried.

Scenes from Greek mythology were an especially popular subject, along with gods and goddesses who were believed to hold sway over daily life—Roman and Greek gods like Mercury, Bacchus, and Apollo were depicted alongside gods from other cultures, such as the Egyptian goddess Isis. A profusion of erotic frescoes have been uncovered across Pompeii in all types of houses and public spaces. The prominent displays of erotic art suggest that sex was celebrated by all sectors of Pompeiian society.

Only two-thirds of Pompeii has been excavated so far.

Pompeii holds the Guinness World Record as the longest continually excavated archaeological site. Despite the centuries of work and research accomplished so far, the huge scale of the dig means that up to a third of the city has yet to be unearthed. Fascinating new finds are being logged every year.

One of the most enduring unanswered questions about Pompeii is the exact date of the disaster. While we have textual evidence from Pliny the Younger dating the eruption to August 24 of the year 79, archaeologists have been puzzled to find many of the people who died in the tragedy wearing thick, wintery clothes. They’ve also uncovered evidence that braziers had been burning and some autumnal foods, like chestnuts, had been harvested—all pointing to a date for the eruption around October. In 2018, diggers found an inscription corresponding to October 17 in the modern calendar and seeming to offer conclusive proof of a later date. But more recent analysis of the potential difference in climate, plus confirmation from other textual sources, suggests Pliny’s date was correct after all. Further excavation may solve the mystery.

You can walk in the footsteps of Pompeii’s citizens.

More than 4 million people visit Pompeii and related sites around the foot of Vesuvius each year. Visitors arrive by train, car, and ferry to explore the ancient streets and gain a taste of life in antiquity. However, to protect the site from overcrowding, the Archaeological Park of Pompeii announced in 2024 that admissions will be capped at 20,000 per day and timed tickets will be required, ensuring this unique site can be preserved for future generations.

Discover More Fascinating Stories About Archaeology: