Paleoart: Visions of the Prehistoric Pastexplores the first 160 years of illustrating extinct species.

No one knows what dinosaurs really looked like hundreds of millions of years ago. The best we can do is hypothesize based on the few fossils we have left. In the preface to the immense coffee table book Paleoart: Visions of the Prehistoric Past (Taschen), artist Walton Ford defines paleoart as “the contemporary art of reconstructing the prehistoric past” in images. If you’ve ever seen an illustration of a dinosaur, that’s paleoart, whether you found it in a school textbook, a science magazine, a kids’ book, and or an encyclopedia. These images, however, depend as much on the artist drawing them as the science underlying their vision. Below are 10 great illustrations of dinosaurs author Zoë Lescaze gathered from the 160-year history of paleoart.

Since the beginning of the field, paleoart has been informed by artists’ visions and biases, fashion, and the limited research of the time. After all, even in the 21st century, scientists still aren’t truly sure what most dinosaurs look like. For decades, we imagined them as a kind of giant lizard, but in fact, they may have looked more like feathered birds. At least in some cases—new research recently contradicted the idea that T. rex had feathers, changing how we think of them yet again. Either way, it’s far from certain how these creatures appeared in real life, and as a result, depicting the paleolithic world has never been a static art.

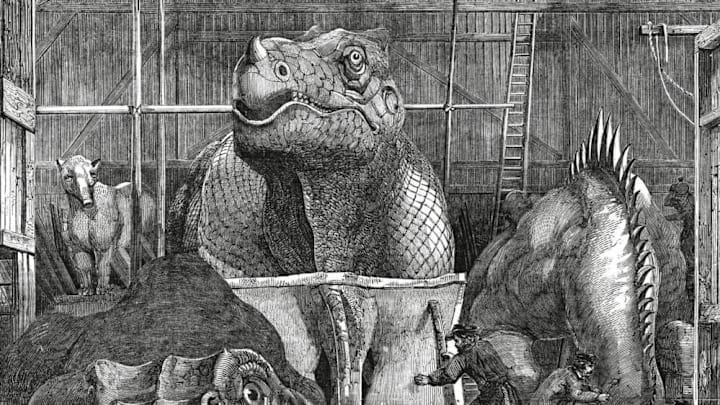

Today’s paleoart can be traced back to 1830, when an English geologist Henry De la Beche used fossil evidence to create a styllized, detailed image of the prehistoric world no human had ever seen. The violent painting showed savage creatures attacking each other from every angle, a theme that later artists would continue to mine. "From the very beginning, artists and scientists portrayed [the marine reptiles] ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs as dire enemies," Lescaze writes of the engraving above, created in 1863. "The reptiles, warring above the waves, became the single most prevalent motif in nineteenth-century paleoart."

These 19th century artists only had a few fragmented fossils to base their visuals upon. “For the earliest paleoartists, fossil bones were blank slates upon which they could project their own imaginative elaborations,” Lescaze notes. The same species could look wildly different depending on the artist, but almost all dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals were depicted as terrifying monsters. One paleoartist even compared himself to Frankenstein, giving life to a horrifying creature. “To study these creatures, and resurrect them in art, was to give form to one’s fears,” Lescaze writes.

Artist Charles M. Knight began his career in paleoart in 1894 and went on to become one of the most influential artists in the field. Impressed by Knight’s talent, the then-president of the American Natural History Museum sent him to study with the legendary paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope, who spent days describing all he could about dinosaurs to the artist. Knight’s dedication to realism set new standards for paleoart. Laelaps “took the enduring theme of dinosaur combat and invigorated it with credible anatomy and volatile movement,” Lescaze writes. Compared to the awkward monsters of previous work, his dinosaurs appeared as realistic, fierce predators in believable habitats.

Paleoart prospered in the Soviet Union, with artists creating everything from tiny sketches to massive mosaics. Lescaze says that these Soviet works of paleoart "are among the most spectacular ever made." Unfortunately, they haven't had much visibility outside Eastern Europe, even since the Cold War ended. "Hidden away within little-known museums across Moscow, artworks both minor and monumental have gone unnoticed, rarely reproduced beyond the bounds of Russian-language websites," she explains.

Konstantin Konstantinovich Flyorov was a Soviet scientist and museum director who often served as an advisor to the film industry on the subject of prehistoric animals. According to Lescaze, his colorful paintings are some of the most unusual in the history of paleoart. Despite his background as a zoologist, though, he "never let science stand in the way of his artistic impulses."

This 1984 terracotta mosaic is a massive visual history across time, starting with prehistoric fish and moving up through dinosaurs and mammals, topped with an image of the Madonna and child. All told, it measures 85 feet by 59 feet.

Rudolph Zallinger's The Age of Reptiles is one of the "largest, best known pieces of paleoart ever made," Lescaze says. The fresco in Yale's Peabody Museum of Natural History measures 110 feet long. Commissioned when the he was just 23, Zallinger spent a year and a half prepping before he began working on the plaster, including an extensive period of research with fossil experts at Yale. Completed in 1947, it traces 300 million years of the evolution of prehistoric creatures from the Devonian Period to the Cretaceous.

Lascaze notes that unlike other forms of natural history art, paleoart doesn't form an easily identifiable visual style. That's to be expected, considering the fact that works like John James Audubon's paintings of birds are based on creatures that look much the same as they did hundreds of years ago. She likens the wide swath of styles in the paleoart genre to a "cacophony of dialects." As the science of paleontology progresses, so must paleoart. "Our conception of certain prehistoric species has transformed so completely that the earliest stages of them, based on a handful of bones, are not even recognizable," she explains. Which is why the sea-monster paintings of the 19th century look so quaint to us now. In 150 years, our 21st century drawings of T. rex probably will, too.

In paleoart, “the lines between entertainment and science, kitsch and scholarship, are often vague," Ford writes in the preface to Paleoart. "This book is like a twofold time machine from a science-fiction comic i would have loved as a child. It allows us to go back in time to see what going back in time used to look like.”

You can find Paleoart: Visions of the Prehistoric Past for $79 on Amazon.