The Sverris saga, a quasi-fictional historical account from the end of the 12th century CE, recaps the reign of the medieval Norwegian king Sverre Sigurdsson. One of the best-known passages describes a military siege that reduced Sigurdsson’s castle, Sverresborg, to ruins—but before it was destroyed, the marauders tried to eliminate its holed-up inhabitants by dropping a dead body down a nearby well, thereby poisoning their water supply.

While using decaying and infected cadavers as a form of biological warfare was a relatively common practice in both the medieval and ancient worlds, historians weren’t sure this particular event actually took place. Although texts like the Sverris saga form the foundation of our understanding of early Nordic history, the contents must always be inspected with a healthy dose of skepticism unless they’re backed up with archaeological evidence.

In the case of the body thrown down the well, researchers got lucky in that regard. Scientists from several Scandinavian universities have identified human remains found in a well at the Sverresborg site, near modern-day Trondheim, as Norwegian in ancestry and dating from the 12th century, corroborating the saga’s account of the castle siege.

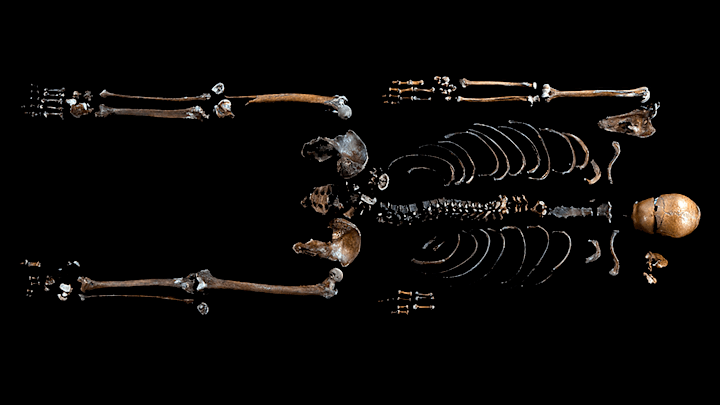

The bones of the “Well Man” were discovered in 1938, about the time archaeological excavations of the Sverresborg site began. World War II interrupted plans to further investigate the well and researchers lacked the technology for any examination beyond a visual description. While the Well Man’s skeleton showed signs of trauma, researchers could not determine whether these injuries occurred before or after his death, though blunt force injuries on the left side of the skull suggested the body could have been thrown.

Studies conducted between 2014 and 2016 revealed that the Well Man was in fact male and had been around 30 to 40 years old at the time of his death. Radiocarbon dating concluded his remains were roughly 900 years old, meaning he—or, rather, his diseased body—could have been present at the raid on Sverresborg.

In the most recent study, published in the journal iScience, researchers ground up one of the Well Man’s teeth to sequence his genome. DNA markers revealed that he likely had blue eyes and blond or light-brown hair. Comparisons of the Well Man’s genome with the DNA profiles in a huge database of modern Norwegians suggested that he hailed from the southernmost area of Norway, which is now the county of Vest-Agder.

To sequence the DNA of a 900-year-old human is one thing, but to corroborate the physical evidence with a tale in a legendary saga is quite another. “This is the first time that a person described in these historical texts has actually been found,” senior author Michael D. Martin, a professor of natural history in the NTNU University Museum at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, said in a statement.

In the future, Martin hopes to apply the technique that identified the Well Man to the remains of Saint Olaf, another medieval Norwegian king, whose is thought to have been buried somewhere inside Trondheim Cathedral.

“There are a lot of these medieval and ancient remains all around Europe,” he said, “and they’re increasingly being studied using genomic methods.”

Read About Other Fascinating Archaeological Finds: