“Have you no sense of decency?” Joseph Welch, special counsel for the U.S. Army, asked Senator Joseph McCarthy on live TV during the Army-McCarthy hearings in 1954. In his efforts to root out alleged communist sympathies in the military, McCarthy had finally bitten off more than he could chew. The hearings ushered in the end of his career, and with it, his campaign now known as McCarthyism.

The Free Speech Center defines McCarthyism as the “practice of publicly accusing government employees of political disloyalty or subversive activities and using unsavory investigatory methods to prosecute them.” The term is often used to denote the period of 1950 to 1954, when its eponym chaired the Senate’s Government Operations Committee and its Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations.

McCarthyism advertised itself as a response to national security threats created by the Cold War, including Soviet espionage. But the movement was bigger than McCarthy himself: Its history stretches back to the First World War and continued after McCarthy left the public eye.

- McCarthyism wasn’t the first “Red Scare” in U.S. history.

- The second Red Scare started in Hollywood.

- Ronald Reagan and Walt Disney were “friendly witnesses.”

- In an infamous speech, Joseph McCarthy claimed dozens of communists had infiltrated the U.S. government.

- Communists weren’t McCarthy’s only targets.

- Roy Cohn prosecuted the Rosenberg spy case before working for McCarthy.

- The Army-McCarthy Hearings began as tit-for-tat accusations.

- Joseph Welch’s question to McCarthy had a double meaning.

- Eisenhower had wanted to get rid of McCarthy for years.

- McCarthyism continued (briefly) after McCarthy’s downfall.

McCarthyism wasn’t the first “Red Scare” in U.S. history.

The original Red Scare began in 1917, the year that Vladimir Lenin and the Bolsheviks seized power in Russia and replaced its parliamentary democracy with a dictatorship of the proletariat. The revolution elevated communism from a fringe philosophy to a serious movement and inspired socialist protests, fueled by rising unemployment and post-World War I economic uncertainty, in the U.S. President Woodrow Wilson’s administration viewed these activities as a major security threat and authorized the McCarthy-like Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer to crack down on alleged troublemakers. The “Palmer Raids” led to tens of thousands of arrests and hundreds of unlawful deportations of Italian and Eastern European Jewish immigrants with alleged leftist sympathies. As with McCarthy, though, persistent lack of evidence against the deportees undercut Palmer’s actions and destroyed his reputation.

The second Red Scare started in Hollywood.

Technically, the second Red Scare can be traced back to the creation of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) in 1938 to investigate alleged disloyalties of private citizens. At the same time, Hollywood-based unions including the Screen Writers Guild (whose members made up a majority of the Hollywood Communist Party’s membership) were demanding better working conditions.

HUAC’s investigations did not develop into a public spectacle until the committee started going after supposed communists in Hollywood in 1947. Lawmakers pressured witnesses to admit any leftist ties and name others in their networks. Some, like screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, refused to answer and were convicted of contempt of Congress. After they served their prison sentences, Hollywood studio heads blacklisted them from the film industry.

Ronald Reagan and Walt Disney were “friendly witnesses.”

While several producers, directors, actors, and writers were held in contempt of Congress for refusing to testify before HUAC, the committee did find an ally in the president of the Screen Actors Guild: Ronald Reagan. The future U.S. president offered his full cooperation to the investigations and appeared in front of the committee as a “friendly witness.” Reagan also established a council in which “innocent” actors accused of communist ties could publicly assert their opposition to communism and voluntarily testify to the same in front of the HUAC leaders, thereby avoiding the blacklist.

HUAC also found an ally in Walt Disney, who had been embroiled in a dispute with striking animators and who believed the unions had been usurped by communists.

In an infamous speech, Joseph McCarthy claimed dozens of communists had infiltrated the U.S. government.

The 1946 midterm elections were characterized by anticommunist rhetoric as the Cold War heated up. Republicans gained 12 seats in the Senate and 55 in the House and took control of Congress. One of the Senate freshmen was Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin, who didn’t make much of a splash until he delivered a Lincoln Day speech on February 9, 1950, in Wheeling, West Virginia [PDF]. He announced that the U.S. was engaged in “all-out battle between communistic atheism and Christianity,” then held up a paper and said, “while I cannot take the time to name all the men in the State Department who have been named as members of the Communist Party and members of a spy ring, I have here in my hand a list of 205.” (He later revised it to 57, but never produced the list to Congress or the press.)

A special subcommittee—the Senate Subcommittee on the Investigation of Loyalty of State Department Employees, a.k.a the Tydings Committee—investigated the allegations and rejected the charges made in McCarthy’s speech as “a fraud and a hoax.” But the outbreak of the Korean War a few months later, coupled with the conviction of State Department official Alger Hiss for perjury (for lying about acting as a Soviet spy), made McCarthy’s accusations seem plausible. His sudden rise as an anticommunist zealot cleared the way for his takeover of the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations in 1953.

Communists weren’t McCarthy’s only targets.

Just days after the Lincoln Day speech, McCarthy linked communists and LGBTQ people as “unsafe risks” to the United States in a speech to the Senate. This would not have a been a shock: In 1946, Congress had given the State Department broad discretion to fire employees it deemed security risks and had purged at least 91 men and women whom it believed were LGBTQ. McCarthy and his allies pressured LGBTQ federal employees to resign or be fired based on the widespread belief that LGBTQ people were morally corrupt and, as such, susceptible to manipulation by communist agents or vulnerable to blackmail [PDF]. This pressure campaign and the fear it caused, dubbed the Lavender Scare, resulted in at least 5000, and up to tens of thousands, of federal employees losing their jobs.

Roy Cohn prosecuted the Rosenberg spy case before working for McCarthy.

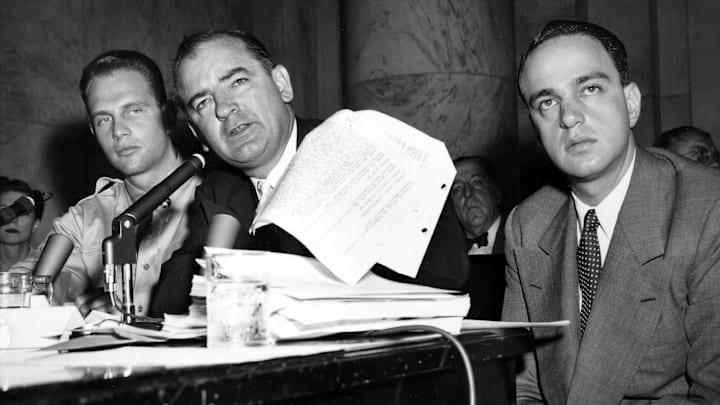

As an assistant district attorney for the Southern District of New York, Roy Cohn had acquired national notoriety for his role as prosecutor in the case against Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, who were convicted of espionage in 1950 for passing top-secret nuclear information to the Soviets. Thanks to Cohn, they were sent to the electric chair. Cohn then went to work for McCarthy as chief counsel for the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations.

The Army-McCarthy Hearings began as tit-for-tat accusations.

The first whiff of McCarthy’s eventual downfall was his insinuation that the Army was harboring a communist spy ring at its Signal Corps laboratories at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey. (Julius Rosenberg had worked there during World War II.) The Army then labeled at least 42 servicemembers as “security risks” in 1953, and McCarthy personally interrogated the suspects, but their lawyers argued they were merely victims of McCarthy’s paranoia. The Army then accused Cohn of attempting to secure special treatment for his very close friend, Army Pvt. David Schine, after he was drafted.

The Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations—which McCarthy still chaired—held hearings on alleged communist infiltration of various government agencies, including the Army, throughout 1953 and into March 1954. The second phase of the hearings investigated McCarthy and Cohn’s alleged request on behalf of Schine, for which McCarthy had to recuse himself from the chairmanship so he could be questioned. The testimony revealed that Cohn had used his vast network to ring up various military officials, including Schine’s company commander and the Secretary of the Army, demanding he receive an officer’s commission and threatening to “wreck the Army” if Schine was deployed overseas.

Joseph Welch’s question to McCarthy had a double meaning.

The Army-McCarthy hearings were televised live, and millions of Americans tuned in to the drama—which peaked when Army counsel Joseph Welch asked McCarthy if he had no sense of decency. Welch was referring to McCarthy’s renegging on an agreement they had made to keep certain names out of public testimony, but many watching the exchange believed Welch was condemning McCarthy’s fear-mongering tactics. Historian Claire Potter, in the podcast Why Now?, suggested there may have been yet another interpretation: “It was another way for Welch to draw attention to the gossip everyone in the room and many in the television audience had heard: that McCarthy’s associates, Roy Cohn and G. David Schine, were allegedly in a romantic relationship.”

McCarthy himself was the subject of a similar rumor. Despite his marriage to his former employee Jean Kerr on September 29, 1953 [PDF]—at the height of the Army-McCarthy hearings, when he was 43 and she 26—many in Washington suspected he “not only had had sex with men but was enamored of one or both of his handsome young staffers,” Potter writes. In the end, speculation about his true role in the Lavender Scare came back to bite him.

Eisenhower had wanted to get rid of McCarthy for years.

It wasn’t just Welch’s damning question that made the TV-watching public sour on McCarthy. The senator’s disrespect for witnesses and rules worked against him. When the Army-McCarthy hearings concluded, McCarthy was censured by the Senate, rendering him powerless and pushing him out of the spotlight.

The censure received vocal support from President Dwight Eisenhower. Having led the Allied campaign against Nazi Germany during the Second World War, Eisenhower had acquired a natural distaste for demagogues who used the mechanisms of democratic government for their own benefit. Eisenhower had wanted McCarthy gone for years, but didn’t feel confident speaking out against him until he had lost his credibility. According to his brother Milton Eisenhower, Ike “loathed McCarthy as much as any human being could possibly loathe another.”

McCarthyism continued (briefly) after McCarthy’s downfall.

Despite Eisenhower’s disdain for McCarthy and the senator’s disgrace, federal prosecution of people with real or alleged communist ties went on. The government continued to arrest, investigate, and punish suspects under the Alien Registration Act of 1940 (a.k.a. the Smith Act) that required non-citizens to register with the U.S. government and made it illegal to advocate for overthrowing the government by force. It was widely used to prosecute and imprison American Trotskyists and others in the Communist Party. Though the law was upheld by the Supreme Court in 1951, the court’s ruling in Yates v. United States in 1957 ended Smith Act prosecutions by distinguishing between concrete advocacy for violent insurrection (which was illegal) and abstract advocacy of the idea of insurrection (which was legal).Yates made it much harder for the government to prosecute communists. McCarthy himself died of hepatitis while in office in 1957, ending his eponymous witch hunts.

Discover More Facts About the Cold War: