When The Last Starfighter was released on July 13, 1984, timing was, perhaps, not in its favor. Competition was stiff—Ghostbusters, Gremlins, Star Trek III, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, and The Karate Kid were still in theaters—and the video game industry was in the middle of a recession spurred in part by a flood of sub-par games. It wasn’t the best box-office environment for an original story with no major stars about a kid whose life hinges on his video-game prowess.

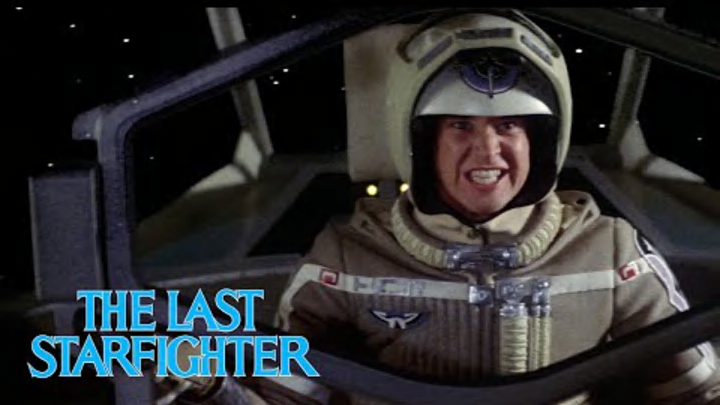

A riff on T.H. White’s Arthurian novel The Sword in the Stone, The Last Starfighter tells the story of teenage video game ace Alex Rogan. Desperate to escape the rural trailer park he calls home, Alex is recruited into a war in outer space when he beats the high score on a video game that, unbeknownst to him, was planted on Earth to find potential “Starfighters”—naturally gifted fighter pilots who could help “defend the Frontier against Xur and the Ko-dan Armada.” It wasn’t exactly a bomb, earning $28 million worldwide on a reported $13 million budget. But it never achieved the astronomical success of 1980s science-fiction standards such as E.T. the Extra-terrestrial and Back to the Future. Its charming cast and ground-breaking visual effects earned it a mostly positive reception upon release, but with no major names attached and no sequels or bestselling merchandise to keep it in the spotlight, The Last Starfighter slipped quietly into the background noise of 1980s pop culture.

At least, it did for a while. Thanks to a series of home video releases, a director and cast happy to celebrate the movie at live events, and the rise of internet fan culture, The Last Starfighter has spent the last 40-plus years quietly becoming a bona fide cult classic. Here are nine things you might not know about the offbeat ’80s space adventure.

- The Last Starfighter was directed by the original Michael Myers.

- The trailer-park setting was a conscious effort to stay out of Steven Spielberg’s territory.

- The effects were created on a historically powerful supercomputer.

- A young Wil Wheaton was mostly edited out of The Last Starfighter.

- It was Robert Preston’s last big-screen role.

- The torture scene was toned down to ensure a PG rating.

- The Beta unit was given more scenes after proving to be a hit with test audiences.

- The Last Starfighter sent viewers searching for a video game that didn’t exist.

- Not even Steven Spielberg could acquire remake rights.

The Last Starfighter was directed by the original Michael Myers.

The Last Starfighter’s director, Nick Castle, studied with Halloween director and cowriter John Carpenter at USC film school. Later, when Castle heard that Carpenter was shooting a movie near his house, he decided to pay his former classmate a visit.

“I said, ‘John, I’m gonna stick on the set as long as you’re gonna shoot down here,’ ” Castle recalled in a 2018 interview with What Culture. Carpenter made the most of Castle’s presence, handing him a mask and coveralls and drafting him into service as the lumbering, murderous Shape, a.k.a. Michael Myers. At least nine other actors have since donned the mask, but Castle made history as the original Michael, one of cinema’s prototypical slashers.

Castle isn’t The Last Starfighter’s only connection to the Halloween franchise. Lance Guest only had two big-screen credits before he was cast as gamer-turned-Starfighter Alex Rogan; one of them was a supporting role in Halloween II, which was produced by Carpenter. As Guest remembers it, The Last Starfighter was in preproduction just as Carpenter was overseeing edits on Halloween II. When Castle got a look at Guest in footage Carpenter showed him, he knew he’d found his star.

The trailer-park setting was a conscious effort to stay out of Steven Spielberg’s territory.

In screenwriter Jonathan R. Betuel’s first draft of The Last Starfighter’s screenplay, Alex and Maggie (then named Skip and Penny) were the kind of suburban teenagers who had taken over movie screens in the 1980s. That didn’t work for director Nick Castle, who was wary of wandering too far into what had become Steven Spielberg’s signature territory.

“Jonathan had set it in suburbia, kind of a Steven Spielberg Poltergeist and even E.T. world, which was, I thought, too derivative of those works,” Castle said in the mini-doc Crossing the Frontier: Making The Last Starfighter. Castle wanted a setting that was both more insular and a little down-at-the-heels. (In the movie, Alex is turned down for a bank loan that would have helped him pay for college.) They settled on the Starlite Starbrite Trailer Court, which the director described to the The Orlando Sentinel in 1984 as “isolated, but charming and wholesome and real Americana.”

The effects were created on a historically powerful supercomputer.

Tron pioneered the use of computer-generated imagery, or CGI, in 1982, but The Last Starfighter represented a major step forward for the technology. To create realistic environments and action sequences, the filmmakers turned to what was then the fastest computer in the world: the Cray X-MP. Digital Productions, the company that provided The Last Starfighter’s computer effects, was the first commercial outfit to acquire the 5.25-ton behemoth, which did computer things at such a furious speed that it required liquid coolant piped through a network of copper tubing to keep it from overheating. Only six X-MPs were in existence at the time; the other five were all being used by the government and the defense industry. Digital Productions’ machine, which Last Starfighter production designer Ron Cobb once compared to the alien-built monoliths in 2001: A Space Odyssey, would also generate effects shots for 2010: The Year We Made Contact and Labyrinth. A 1984 issue of Computing Today reported that the price tag for The Last Starfighter’s effects was about $3 million for its 25 minutes of CGI, or roughly $2000 per second of footage.

A young Wil Wheaton was mostly edited out of The Last Starfighter.

Three years before he joined the cast of Star Trek: The Next Generation as future ensign Wesley Crusher, Wil Wheaton earned one of his first big-screen credits as “Louis’s friend” in The Last Starfighter. He filmed a few lines of dialogue, but that footage was ultimately cut from the movie, leaving Wheaton as simply a face in the background at the Starlite Starbrite Trailer Court. Wheaton would have considerably better luck with his next theatrical film: 1986’s Stand by Me, where he’d lead the cast in his breakout role as the young Gordie Lachance.

It was Robert Preston’s last big-screen role.

Robert Preston was a veteran stage and film actor with roles in Victor/Victoria and How the West Was Won, but he’s best remembered for his starring turn as con man Harold Hill in 1962’s The Music Man. It was that role that inspired The Last Starfighter screenwriter Jonathan R. Betuel to suggest casting him as the wily alien Centauri, the designer of the video game that draws Alex Rogan into a space war. Once Preston was onboard, the role was rewritten to more closely mirror his Music Man character. Preston would appear in just two more movies, both made for television, before dying of lung cancer in March 1987 at the age of 68.

The torture scene was toned down to ensure a PG rating.

The Last Starfighter is mostly remembered for its good-natured charm, but it includes one notoriously unsettling scene: The villainous Xur orchestrates the torture of a captured Star League spy and broadcasts the grim spectacle to Starfighter Command—and a grossed-out Alex Rogan.

If 8-year-old you was unnerved by the scene, imagine how you would have felt if it had made it to the screen intact. The instrument of torture is a laser that slowly melts the spy’s head, beginning at the top of his skull. In the final version, the scene only lasts a few seconds and cuts away just as the spy’s forehead begins to glow red. In the original scene, Alex and company watch the spy’s death as the laser melts his entire head.

“It hurts when you see someone’s brains fry,” Castle observes in audio commentary for a 1999 DVD release of the film. The death was deemed too grisly and cut from the movie, leaving viewers to draw their own conclusions about the spy’s fate. In a 1984 interview with The Cincinnati Post, Castle said he never considered pursuing the newly minted PG-13 rating, which might have let him use the scene as it was conceived. The Last Starfighter went out in July 1984 with a shortened torture scene and a PG rating; less than a month later, Red Dawn became the first PG-13 film to hit theaters.

The Beta unit was given more scenes after proving to be a hit with test audiences.

One of The Last Starfighter’s most memorable elements is the Beta unit, Alex Rogan’s android double that is left on Earth to replace him once Rogan is whisked off to space. The Beta, which is fundamentally unprepared for the business of pretending to be human, is the source of much of the film’s humor, and it was such a hit with test audiences that the cast and crew were pressed back into service to beef up its role in the movie. Guest had gotten a haircut since filming his scenes, forcing him into a poofy wig for the reshoots. Matters were further complicated when Guest became ill during reshoots and required excessive makeup to correct his skin tone.

The Last Starfighter sent viewers searching for a video game that didn’t exist.

According to 1984 newspaper reports, viewers attending a test screening of The Last Starfighter left the theater and headed directly for their favorite arcade, hoping to try their hand at the game Alex Rogan had played onscreen.

“They were looking for the game as if there really was a Starfighter and they were dying to play it,” Castle said in a 1984 interview with The Philadelphia Inquirer. That game was in development at Atari, but it would never reach stores.

According to arcade-history.com, Atari’s The Last Starfighter was a first-person shooter game that employed some of the same mechanics as the company’s 1983 Star Wars tie-in. But The Last Starfighter failed to set the box office on fire, and the sophisticated graphics and gameplay meant the cabinet version would have set an arcade owner back some $10,000 in 1984—about $31,000 in today’s currency. Atari decided the movie wasn’t popular enough to justify that price tag, so production was canceled before the game was finished. An 8-bit home version also got the axe, but Atari’s efforts weren’t entirely wasted—that game would be reworked and released as Solaris and Star Raiders II in 1986.

You can read former Atari VP Chris Horseman’s proposal for the original Last Starfighter game here.

Not even Steven Spielberg could acquire remake rights.

As The Last Starfighter’s fan base has steadily grown over the decades, one of the most-asked questions is “Why hasn’t there been a sequel?” It’s certainly not for lack of interest. Director Nick Castle was working on a sequel sometime around 2005 that would have brought back original stars Lance Guest and Catherine Mary Stewart as the parents of a new Starfighter, but the project was eventually abandoned. A sequel was reportedly in development in 2008, but nothing came of that attempt either. Even Steven Spielberg tried to secure rights to The Last Starfighter—and got nowhere. In 2014, Seth Rogen tweeted that, when he revealed to the director that he’d tried and failed to acquire the rights, Spielberg had admitted that he’d also come up empty. The following year, a hybrid television-VR project called The Starfighter Chronicles was announced, but no further news has surfaced.

By 2018, Last Starfighter screenwriter Jonathan Betuel had partnered with Gary Whitta, screenwriter of After Earth and The Book of Eli, on a sequel script called The Last Starfighters. Whitta posted a concept art sizzle reel to his YouTube channel in 2021 (above), but in 2022 he tweeted that the project had stalled. As of January 2025, the only other Starfighter project to make it beyond the page is an off-Broadway musical that opened at New York City’s Storm Theatre in October 2024.

In a 2024 episode of the 1980s Now podcast, Betuel described a convoluted rights situation that has played out over the decades since The Last Starfighter’s release. He long believed that Universal owned the rights to the movie, but when the studio contacted him to discuss a possible series of TV movies, his attorney reviewed the terms and realized the studio’s rights to the property had expired. It took a couple years of legal wrangling, but Betuel was eventually able to secure all domestic distribution rights to The Last Starfighter, placing him in the driver’s seat for any potential sequels or remakes.

Read More Stories About Movies: