Between 17,000 and 12,000 years ago, unnamed artists covered the extensive Lascaux cave system in France’s Dordogne region with hundreds of paintings of animals and abstract shapes. The astonishing paintings were discovered by accident in 1940 and captured the world’s attention, offering a tantalizing glimpse into a prehistoric culture. Below are 12 things you should know about the cave paintings at Lascaux.

- Four schoolboys stumbled onto the Lascaux cave system while chasing their dog.

- Dordogne is rife with decorated caves.

- People occupied Lascaux cave in three distinct periods.

- The artists used a variety of techniques and tools.

- The pigments were made from minerals.

- The artists probably used scaffolding to paint near the cave’s ceilings.

- A sandstone lamp revealed how the cave was illuminated.

- Tools found on the cave floor reveal the culture’s sophistication.

- There is just one complete human-like drawing in the cave.

- Lascaux’s Hall of Bulls contains the largest known animal image in cave art.

- No one knows what Lascaux’s paintings mean.

- The caves are closed to the public—but you can experience an exact replica of them.

Four schoolboys stumbled onto the Lascaux cave system while chasing their dog.

In September 1940, four teenage boys were searching for their lost dog in woodlands near the village of Montignac in southwest France when they came across a mysterious hole in the ground. The boys clambered down the shaft and, to their amazement, discovered an entire cave system covered in ancient artworks.

Excited by their discovery, the boys began charging friends a modest admission fee to see the cave paintings, and soon the news spread that something special had been discovered. The boys’ teacher, a member of the local prehistory club, came down to take a look—and was astounded by what he saw. He instructed the boys not to touch the precious paintings and to protect the site from vandals while he summoned the authorities. Archaeologist Henri-Édouard-Prosper Breuil was the first to scientifically inspect the cave and he quickly realized the importance of the site. He confirmed the cave paintings (known as parietal art) to be authentic.

Dordogne is rife with decorated caves.

Dordogne has the highest concentration of decorated caves, shelters, and habitation sites from the Upper Paleolithic in Western Europe, making it a vitally important region for prehistorians. The geology of the area and the climatic thawing and freezing caused by previous ice ages formed numerous cave systems that provided safe and dry spaces for Paleolithic peoples to shelter in. The Vézère valley alone, where Lascaux is situated, has 147 prehistoric sites dating from the Paleolithic period and 25 decorated caves. UNESCO listed the valley as a World Heritage Site in 1979.

People occupied Lascaux cave in three distinct periods.

The parietal art at Lascaux has been dated to the early Magdalenian culture of the Upper Paleolithic period, roughly 17,000 to 12,000 years ago, which makes it more modern than the cave art discovered at nearby Chauvet. The cave at Lascaux was thought to have been occupied in three separate phases. The first period was identified by some charcoal discovered in areas known as the Nave and Shaft, while the second period was revealed by numerous objects found throughout the cave system that aligned it with the period when the art was created. The final time of habitation was a brief moment that left traces only at the cave entrance where the natural light would have reached. The types of objects found in the cave suggest that only the first few meters of the cave closest to its entrance were ever lived in—the rest was visited purely to make art, indicating it may have been a sacred or ceremonial space.

The artists used a variety of techniques and tools.

The art in the caves was created over generations, with numerous artists leaving their mark and using different techniques. Most images were engraved or carved into the stone or were drawn or painted onto the white calcite walls. No archaeological evidence for paintbrushes has been uncovered, so researchers have suggested that the paint may have been applied using clumps of moss or hair. Archaeologists have also unearthed hollow bones, which the artists may have used to blow pigment onto the walls to achieve larger blocks of color.

The pigments were made from minerals.

Chemical analysis of the matte, earthy tones that have survived to the present day on the cave walls revealed they were largely derived from minerals mixed with water to act as a binder. (Any pigments from organic sources have long since disappeared.) Reds are made from hematite, yellows come from goethite, and the black pigment derives from manganese oxide, a mineral which, in France, was found only in Dordogne until the 20th century. Manganese was plentiful and easy to extract around Lascaux, likely explaining why it was used to create the black pigment instead of charcoal, which is commonly seen in other cave paintings across France.

The artists probably used scaffolding to paint near the cave’s ceilings.

Some drawings at Lascaux are 2.5 to 3.5 meters (8.2 to 11.4 feet) from the floor of the cave near the chambers’ ceilings. To archaeologists, they present a conundrum: How did the artists reach such heights? The assumption is that they must have used scaffolding, but there’s scant evidence to show how the structures might have been built.

In the 1950s, archaeologist André Glory noted the remains of some interlocked beams at the edge of the Axial Gallery, one of the most decorated chambers in the system. He argued the beams must have represented a scaffold, but lack of evidence elsewhere suggested the structure may not have extended to other rooms in the cave. What is certain, though, is that the creation of Lascaux’s cave paintings must have been a group effort. Multiple people would have been required to build the scaffolds or perches, hold torches or lamps to provide light, and wield the painting and drawing tools.

A sandstone lamp revealed how the cave was illuminated.

In 1961 or 1962, Glory discovered a beautiful red sandstone lamp resembling a large spoon and decorated with engraved chevrons on its handle in the floor of the Shaft. He dated it to around 17,000 years old, placing it in the Magdalenian culture of the Upper Paleolithic in Western Europe. Sooty remnants in the bowl of the lamp were analyzed and found to be the remains of a wick made from juniper. This specimen was the most finely carved of the more than 100 lamps that have been identified at Lascaux, revealing how the Paleolithic artists lit the dark interior of the cave.

In a 1993 paper in the journal Leonardo, Fordham University professor Edward Wachtel argued that flickering light from an animal-fat lamp would have made the images in Lascaux appear to move. He drew from his own experience, having visited several decorated caves in France with a guide carrying a gas lantern and having seen how certain lines and shapes became animated when illuminated. While we can’t know for sure how Paleolithic peoples experienced the caves or if they intentionally created such scenes, Wachtel suggested that dynamic images of animals may have constituted a proto-cinematic experience.

Tools found on the cave floor reveal the culture’s sophistication.

Compared to other cave sites in France, Lascaux has produced a relatively large number of objects from its chambers. Some are associated with art-making, such as grinding stones and mortars to make pigments, flint tools used to engrave the walls, and a needle and awl made from bone. Archaeologists have also discovered 16 fossilized shells, three of which had holes drilled through them so they could be worn as jewelry. An analysis of the shells indicated they came from western France, several hundred kilometers from Lascaux, hinting that the cave-dwellers traveled long distances to obtain them or maintained a trade network with other Magdalenian groups.

There is just one complete human-like drawing in the cave.

The Lascaux cave complex contains more than 600 paintings and around 1500 engravings of animals, abstract symbols, and a single human-like figure. (Humans are rarely depicted in any of the decorated caves discovered so far.) This figure has puzzled art historians due to its very strange presentation and its rarity. The figure is falling backwards away from a bison; it is either crying out or has the head of a bird (some have nicknamed it “bird-man”), and it has an unmistakable erection. Beside the prone figure lies a staff with a bird on top, and behind it is a rhinoceros facing away from the figure and appearing to poop in its direction. The whole tableau has invited endless speculation and numerous theories about its meanings, but it’s unlikely that we’ll ever truly understand what the artist intended.

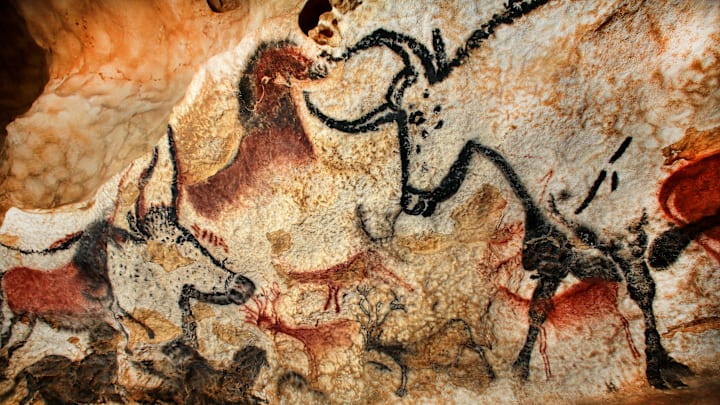

Lascaux’s Hall of Bulls contains the largest known animal image in cave art.

Horses are the most frequently depicted animals in Lascaux with a total of 364 images, followed by groups of felines, stags, bison, and others. One of the most celebrated scenes in Lascaux is the four huge black bulls or aurochs (an extinct species of giant wild cattle) galloping across the walls in the Hall of Bulls. The largest of the bulls is 17 feet long, making it the biggest known depiction of an animal in parietal art. Several of the animal groupings show that Paleolithic cave painters were skilled in the use of perspective: In side views of running bison, one of the animals’ hind legs is crossed over the other, demonstrating advanced comprehension of the artistic technique.

No one knows what Lascaux’s paintings mean.

Art historians have long attempted to understand why ancient peoples made art in dark and often inaccessible caves and why they chose to depict what they did. French archaeologist Norbert Aujoulat, who carried out research at Lascaux between 1988 and 1999, mused that the images reflect the changing of the seasons and the passing of time. He noted that the animals were always portrayed in the same sequence with horses first, then aurochs, then stags. The horses resemble how they would look in the spring, while the aurochs align with the summer and the stags are represented with their autumnal features. Aujoulat proposed that the scenes represent the natural biological cycles of the animals that lived alongside the artists and potentially could be linked to fertility rites.

The caves are closed to the public—but you can experience an exact replica of them.

People clamored to see the incredible, vibrant art when Lascaux opened to the public in 1948. Unfortunately, the dank conditions of the cave, the artificial lighting installed for viewing, and the collective breath of thousands of visitors damaged the delicate art. The paintings’ colors faded and fungi, bacteria, and mineral crystals soon bloomed on the cave walls. To make matters worse, the cave’s floor was lowered to improve accessibility, resulting in the loss of important archaeological context. Authorities closed the site to visitors permanently in 1963.

Fortunately, modern visitors still have options. An exact replica of the Hall of Bulls and Axial Gallery, known as Lascaux II, opened in 1983 near the original cave. Tours are led by guides with flashlights, allowing guests to share the feeling of the cave’s discovery in 1940. Nearby in Montignac, the International Center for Cave Art/Lascaux IV opened in 2016 and contains a complete facsimile of the entire cave, plus high-tech galleries and a cinema showing the connections between Lascaux’s prehistory and contemporary art and culture. And, France’s Ministry of Culture offers a 3D virtual tour so you can explore the caves from the comfort of your home. These recent innovations ensure the beauty of this ancient art will continue to inspire and enthrall.

Read More Fascinating Stories About Archaeology: