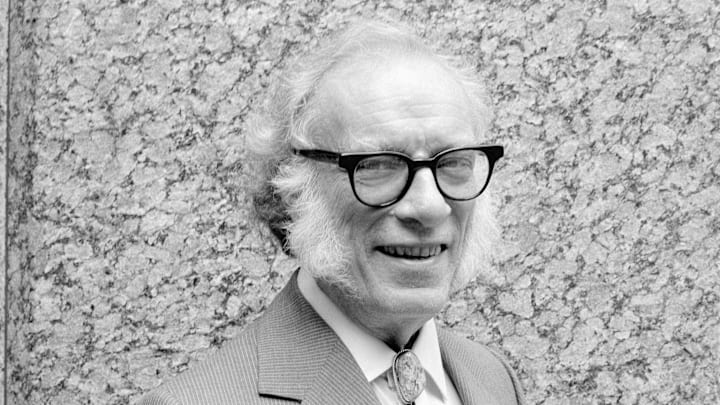

If there was one author Henry Bott disliked more than any other, it was Isaac Asimov.

Bott, a book reviewer for the science fiction publication Imagination, had spent years lobbing insults at the respected writer and his work. Of Asimov’s Second Foundation, published in 1953, Bott wrote that Asimov was “neither a writer nor a storyteller” and could churn out only “elephantine prose.” Second Foundation was, Bott observed, “not a good book.”

After another seemingly personal review followed, this one for The Caves of Steel, an irritated Asimov penned a fiery retort in which he referred to Bott as “The Nameless One” in the fan publication Peon [PDF]. More volleys followed, and Asimov continued to take a shelling.

But when Asimov picked up the February 1955 issue of Imagination, he was amused to read Bott’s enthusiastic review of Lucky Starr and the Oceans of Venus, a spirited sci-fi adventure yarn that was part of an ongoing series by writer Paul French. The story, Bott effused, was gripping and worthy of a reader’s attention, though he felt it fell short of the young adult works by Robert Heinlein.

Asimov put the magazine down and began typing a letter to Imagination. This time, he would not attempt to argue with Bott. “I am sure that Mr. French, on reading this review, would feel quite good about the kind words and would feel no rancor at all about the eminently fair criticism,” Asimov wrote. “In fact, I am sure he would say he does his best to make his juveniles as good as Mr. Heinlein’s, and that perhaps he will improve as he continues to try.

“I am positive that Mr. French would say all this. The reason I am positive is that Paul French and Isaac Asimov are the same person.”

Lucky Break

Bott’s opinion was in the minority. By the 1950s, Asimov had developed a reputation for brainy science fiction that existed alongside his academic work. Having earned a Ph.D. in chemistry, Asimov taught and even co-authored a biochemistry textbook, Biochemistry and Human Metabolism, while pursuing his fiction career. In 1951, he published Foundation, the first in a series about a galactic empire toppling in a manner similar to Rome.

In March 1951, Asimov had lunch with his agent, Frederick Pohl, and Doubleday book editor Walter Bradbury. (Bradbury was no relation to Ray Bradbury, though the two did work together on The Martian Chronicles.) The two wanted to jointly pitch him on a project that had been percolating in both of their minds. Television, they insisted, was going to take on an even greater presence in popular culture. If Asimov could conceive and develop a book series in the pulp tradition about a space adventurer, it could be adapted for the new medium and perhaps run for decades, making all three men millions in the process.

To illustrate their point, they reminded Asimov of The Lone Ranger, a popular Western character who had been running on radio to great success. The book series, they proposed, would be in line with that—only the hero would be a space ranger.

Asimov had one reservation: He believed television was mostly terrible. Aside from some game shows and variety series, nothing had made any seismic impact. The first real classic of the medium, I Love Lucy, was months away from its debut.

“What happens if they put out something I don’t like with my name on it?” he asked Bradbury.

Bradbury made a suggestion: Use a pen name. That way, a miserable, second-rate show wouldn’t reflect poorly on him.

Asimov was pleased by the idea. Inspired by Cornell Woolrich, who took on the name William Irish, Asimov used a nationality and became “Paul French.”

Pseudonym chosen, Asimov began working on what would become David Starr, Space Ranger, in June 1951. Barely six weeks later, he was done with the manuscript and sent it off.

David Starr, Space Ranger features the titular character, a biophysicist some 5000 years into the future, who goes undercover on Mars after discovering a plot to contaminate the food supply. There are fights, encounters with hostile aliens, and shootouts with laser blasters—much of it familiar to pulp readers of the time.

Doubleday was happy with the debut novel. Asimov was not. He wanted to make a key change.

Name Withheld

Asimov had named David Starr after his unborn son: His wife was pregnant as he was writing the book. But David wasn’t really sufficient for the kind of sci-fi space opera Asimov was crafting. He gave Starr a nickname, “Lucky,” and titled the second book Lucky Starr and the Pirates of the Asteroids, which Doubleday released in 1953.

Asimov also found the “space ranger” conceit clumsy, so that was dropped for the third book in the series, Lucky Starr and the Oceans of Venus, released in 1954. This was the volume that reviewer Henry Bott embraced, which prompted Asimov no end of amusement.

More books followed: Lucky Starr and the Big Sun of Mercury; Lucky Starr and the Moons of Jupiter; Lucky Starr and the Rings of Saturn. But in spite of their editorial plotting, a Lucky Starr television series never materialized.

Asimov believed the issue was Rocky Jones, Spacer Ranger, an unrelated sci-fi show for kids that premiered in 1954. Like Lucky Starr, Rocky Jones was a kind of space cop who investigated galactic problems. Unlike Lucky Starr, Rocky Jones didn’t benefit from Asimov’s talents. Just 39 episodes were produced. Rocky Jones seemed to flatline any chances Lucky Starr had to mount a similar premise on television.

Given the lack of a television show, Asimov no longer needed the pretense of a pseudonym. He even inserted a mention of a popular trope found in his other novels that summarized the ethical obligations of artificial intelligence. “I made no effort to hide my identity, therefore,” Asimov wrote, “and in Lucky Starr and the Moons of Jupiter I even introduced the three laws of robotics, which was a dead giveaway to Paul French’s identity for even the most casual reader.”

A seventh book, Lucky Starr and the Snows of Pluto, was in the planning stages when Asimov decided to pivot to nonfiction work. That was the end of Lucky, though Asimov pointed out that it was no small portion of his career. With the six books totaling 250,000 words, it was roughly the same size as his Foundation series. (Subsequent editions credited Asimov “writing as Paul French.”)

As for the ornery Henry Bott: After Asimov dashed off the letter to Imagination outing himself as French, he was amused to see it published in a later issue. In a rebuttal accompanying the letter, the magazine’s editor, William L. Hamling, asserted that Bott actually knew French was Asimov but that the acknowledgment had been left out due to space constraints—an excuse that Asimov would later label “so lame.”

Additional Sources: In Memory Yet Green; In Joy Still Felt.

Read More About Your Favorite Books: