In the late 1970s, Vietnam veteran Jan Scruggs was growing increasingly frustrated by domestic sentiment toward Vietnam veterans. While the war itself was among the most controversial conflicts the United States had ever entered, there was no denying tens of thousands of soldiers had given the ultimate sacrifice for their country. Scruggs believed those servicemen and women deserved a permanent tribute that would not only honor them but perhaps help America come to terms with its complex feelings toward the war.

“The Memorial had several purposes,” Scruggs said. “It would help veterans heal. Its mere existence would be societal recognition that their sacrifices were honorable rather than dishonorable. Veterans needed this, and so did the nation. Our country needed something symbolic to help heal our wounds.”

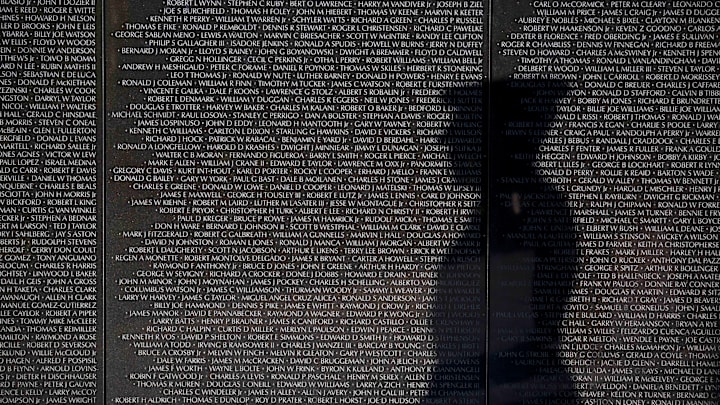

Less than three years later, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, a sprawling black granite tribute to the 58,000 people who lost their lives during the Vietnam war, was unveiled. Each name has been etched in the v-shaped stone, which is made up of two sections that are each over 246 feet, 8 inches long by 10 feet, 1.5 inches tall.

As the 50th anniversary of the conflict’s end in 1975 arrives, take a look at some of the more intriguing facts, figures, and trivia behind one of the most poignant—and popular—destinations at Washington’s National Mall.

- The Vietnam Veterans Memorial was the result of a contest.

- The design for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial was controversial.

- The names on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial aren’t hand-carved.

- The Vietnam Veterans Memorial dedication ceremony took nearly a week.

- The names on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial are chronological for a reason.

- Each name on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial has a symbol.

- Some living Vietnam War veterans were accidentally added to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

- Names can be added to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

- The Three Servicemen statue has a controversial feature.

- The Vietnam Women’s Memorial took 10 years.

- Mysterious cracks have appeared on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

- Some names on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial are misspelled.

- Items left at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial find a home.

- The v shape in the Vietnam Veterans Memorial doesn’t stand for Vietnam.

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial was the result of a contest.

Jan Scruggs, lawyer and veteran Robert Doubek, and other associates formed the nonprofit Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund in 1979 with an eye on launching a memorial by Veterans Day 1982. The problem was that no national monument had ever been conceived and constructed in such a short period of time. But the group was determined, and within months had secured support from Senator John Warner for a site—two acres near the Lincoln Memorial—and had mounted a successful fundraising effort endorsed by First Lady Rosalynn Carter, Bob Hope, Nancy Reagan, and others.

The Fund then decided to host an open competition for the actual design of the memorial. Entrants were bound by a handful of rules—the memorial had to include the names of all those who lost their lives and had to be apolitical in nature—but were otherwise free to let their imaginations go.

A jury of architects, half of whom were themselves veterans, combed through the submissions, including one that proposed a giant helmet riddled with bullet holes. In 1981, 21-year-old Yale undergraduate Maya Ying Lin was chosen out of 1421 entries. Her plan for a reflective granite wall installed below grade and carrying the names of the dead and missing in chronological order—with the far ends of the wall touching to represent a completed circle—was everything organizers had been looking for. (Lin, however, didn’t get as warm a response from Yale: Her plans, which were submitted for course work, received a B grade.)

The design for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial was controversial.

While Lin’s minimalist approach to the memorial satisfied the judging panel and the Veterans Fund, it had its share of detractors that thought the idea was too unconventional. Some, including donor and billionaire H. Ross Perot, found the black granite too oppressive (he called it “a tombstone”) and believed the monument should have more character or adornment to celebrate the heroism of soldiers. Others took issue with Lin being of Asian descent as well as too young to fully comprehend the horrors of the war.

The controversy threatened to mar or even cancel the plans. Finally, with Senator John Warner mediating, both supporters and critics were able to compromise: A statue of a serviceman would be added in front of the wall. (The idea later morphed into the Three Servicemen statue, which opened in 1984.)

The names on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial aren’t hand-carved.

Though it was Lin’s original idea to have all the names on the memorial carved by hand, time constraints made that impractical. Instead, the Memorial Fund contracted a sandblasting company to speed the process up. On the advice of a Cleveland man named Larry Century, a plastic sheet with names was applied to the stone surface. After being exposed to water, the stone retained the names, which would then be quickly etched; 18 panels could be completed in a week using this method.

The text for the beginning and end dates, as well as an epilogue and prologue, remained chiseled by hand.

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial dedication ceremony took nearly a week.

Ground was broken for the wall in March 1982. Incredibly, it was ready to open to the public by November of that year. Between November 10 and November 14, a number of events coinciding with its debut were held. Volunteers read all 58,000 names on the wall out loud, which took three days; a Saturday parade drew over 15,000 participants. Jan Scruggs later recalled it was “like a Woodstock atmosphere in Washington.”

The names on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial are chronological for a reason.

Names on the wall are not in alphabetical order. Instead, they’re in order of the date of death, as per Lin’s design. The reasons are twofold. It permits loved ones to find the deceased using the date, which reduces confusion when service members share a similar or common name; the order also keeps soldiers who died together close to each other on the memorial itself.

Chronological order isn’t the only way to find names, however. A directory allows family and friends to find names alphabetically, which then directs them to the correct granite panel and line number on the wall itself. John Doe, for example, might be 5E—panel 5 on the east wall. The line number counts from top down.

Each name on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial has a symbol.

Symbols etched into the granite on the wall offer some context for the names. A diamond symbol means the service member is confirmed to be deceased or presumed deceased; a cross sign means they were either missing or a prisoner of war at the time of the monument’s construction in 1982. If a solider is repatriated, or has their remains brought back into the country, then the diamond can be superimposed over the cross.

If a listed name is ever found to be alive, the cross would then be altered to come inside of a circle. Unfortunately, that has yet to happen, though at least one engraved name did resurface: In 1996, a veteran named Mateo Sabog appeared in Georgia asking for benefits. Sabog had left the Army in 1970 and had been presumed dead—but he never even made it to Vietnam, despite the country returning remains it claimed were his. He died in 2007.

Some living Vietnam War veterans were accidentally added to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

With 58,000 names on the wall, mistakes are unavoidable. A total of 14 men added to the wall were actually alive at the time of the construction, indicating a clerical error. When this happens, the name is removed.

Names can be added to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

A total of 57,939 names were on the wall when it was dedicated in 1982. As of May 2021, there are 58,281 names. Service members can be added if information comes to light about their service and end of life within defined combat zones of Vietnam. Decisions about adding names fall under the purview of the Department of Defense.

The Three Servicemen statue has a controversial feature.

Near the Memorial is a more conventional tribute: a bronze statue of three servicemen positioned under a flagstaff dedicated in 1984. Some have questioned why one of the men depicted has a bandolier with ammunition for his M-60 machine gun facing upward instead of facing the ground, as is customary. Sculptor Frederick Hart referenced the choice in 1993, saying that he believed different military units might have different habits or rules. He felt the detail was accurate based on military members he had spoken with.

The Vietnam Women’s Memorial took 10 years.

Of the 58,000 names on the wall, the National Park Service reports that just eight are women. Yet up to 10,000 served as nurses during the conflict. In the early 1980s, one nurse, Diane Carlson Evans, began an effort to get recognition for women who provided that needed medical assistance. Evans started the Vietnam Women’s Memorial Project, but it was quickly met with resistance. Women, critics argued, didn’t serve in combat roles. In fact, several were wounded in the line of duty.

After a decade of petitioning and lobbying, the Vietnam Women’s Memorial was dedicated on November 11, 1993. Its bronze nurses tending to a fallen soldier are located 300 feet from the Three Servicemen statue.

Mysterious cracks have appeared on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

While the granite panels of the wall may seem immutable, they’re still vulnerable. In 1984, two walls were removed for examination after the discovery of 14 small cracks. The phenomenon repeated itself in 1994 and again in 2009. Geologists aren’t exactly sure what causes the cracks, though one theory is that the stone might bow when heated up by the sun. The Memorial Fund has blank replacement panels in storage in the event one or more become irreparably damaged.

Some names on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial are misspelled.

Despite the efforts of organizers, errors are virtually unavoidable when it comes to the sheer number of names on the wall of the memorial. In 2012, Jan Scruggs told NPR that roughly 100 names were misspelled or had errors when the walls were first engraved in 1982. Of those, 62 were corrected.

Depending on the error, the name can be revised in place or, if it requires significant edits, moved to another part of the memorial. But not all families want that: Some prefer to keep the name of a fallen soldier next to his fellow service members, even if it means the error stands. Evangelista Pagan Rodriguez’s first name is misspelled as “Evangelis,” but adding the ta would mean relocating it. The Rodriguez family, Scruggs said, wanted the name to remain in place.

Items left at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial find a home.

Many visitors to the wall feel compelled to leave items in acknowledgment of the sacrifices made by soldiers—letters, handmade gifts, and more. As many as 400,000 items have been left at the site since 1982. Virtually all wind up in the hands of the National Park Service, which catalogs and stores them as part of their Vietnam Veterans Memorial Museum collection. Things left are essentially treated as donations and offer an emotional record of those visiting the wall.

Some precautions do need to be taken. Military dog tags, for example, were often stamped with a soldier’s social security number. The NPS blurs out personal information when sharing such items during exhibits or on social media.

The v shape in the Vietnam Veterans Memorial doesn’t stand for Vietnam.

The walls of the memorial converge into a v shape. But contrary to popular belief, the v isn’t meant to stand for Vietnam or veterans. Lin only intended for it to be distinctive enough to compel bystanders to walk up to it and pay their respects.

Read More About History: