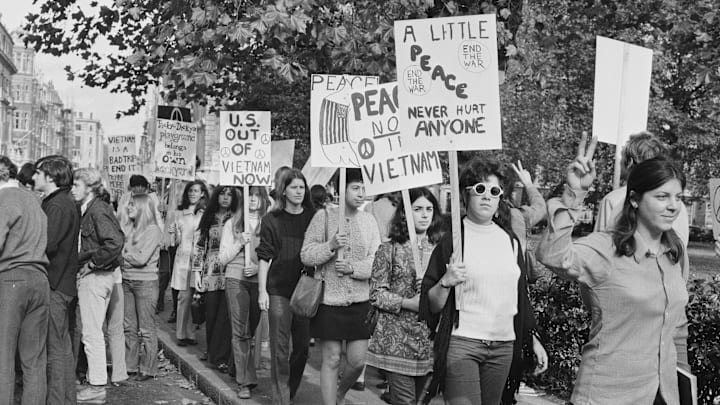

In March 1965, the United States became involved in the Vietnam War to prevent communism from spreading to that recently divided country’s southern half. That same year, a nationwide protest movement began taking shape at home. Over the next decade, people from all walks of life set aside their differences to call on the government to stop the slaughter of Vietnamese civilians and bring American soldiers home.

Though not the first of its kind, the protest movement in response to the Vietnam War was bigger and better organized than any anti-war activity U.S. society had seen up to that point. The Vietnam War was the first conflict to be covered on television, keeping the public informed of military operations as they happened. The anti-war movement also intersected with other social currents of the time, including the civil rights movement and the 1960s counterculture exemplified by music festivals like Woodstock.

While historians agree the anti-war movement was not the sole reason for America’s eventual withdrawal from the war (the prowess of the Vietcong, overburdening of the U.S. economy, and Washington’s relations with communist China were just as important), its inventive and effective forms of protest—10 of which are listed below—helped force the government’s hand.

- Young men burned their draft cards.

- Students led the massive March on Washington to End the War in Vietnam.

- Martin Luther King, Jr. spoke out against the war.

- A coalition of activists launched the March on the Pentagon.

- News coverage of the My Lai Massacre divided public opinion.

- The peace movement encountered violence at the 1968 Democratic National Convention.

- The Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam marked a tipping point.

- The National Guard opened fire on Kent State students.

- Major musicians wrote the soundtrack to the anti-war movement.

- The anti-war and counterculture movements came together at Woodstock.

Young men burned their draft cards.

One of the first ways that people started protesting the war was by burning their draft cards, which were documents issued to all men registered with the Selective Service and who could be drafted into the conflict. Initially, setting fire to the cards was a less radical, alternative form of protest compared to rioting or moving to Canada. The act was turned into a criminal offense by the Draft Card Mutilation Act of 1965, a law that was ultimately upheld by the Supreme Court despite legal challenges claiming that it violated the First Amendment.

Students led the massive March on Washington to End the War in Vietnam.

On April 17, 1965, Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), a national student activist group, organized the largest peace protest in American history up to that point, bringing between 15,000 and 25,000 students to Washington, D.C., for a march that began at on the National Mall and ended at the Capitol. Popular folk singers like Joan Baez and Phil Ochs, and other activist groups including Women Strike for Peace, supported the action. The Nation described the protestors as a “new generation of radicals.”

Martin Luther King, Jr. spoke out against the war.

The civil rights leader denounced U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War as early as 1966, when, while testifying before a congressional committee on government budgets, he argued the war effort redirected funding that could be better used for fighting poverty at home.

King made his first appearance at an anti-war protest in Chicago the following year, telling demonstrators that “the bombs in Vietnam explode at home—they destroy the dream and possibility for a decent America.” Connecting the war to the civil rights movement, he also said the conflict was “taking the Black young men who had been crippled by our society and sending them 8000 miles away to guarantee liberties in Southeast Asia which they had not found in southwest Georgia and East Harlem.”

A coalition of activists launched the March on the Pentagon.

Led by the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam, the March on the Pentagon on October 21, 1967, was the first nationally coordinated demonstration against U.S. foreign policy. That weekend, more than 100,000 activists gathered in Washington for performances by folk music stars and appearances by Abbie Hoffman, Norman Mailer, and other speakers. Then, having assembled at the Lincoln Memorial on October 21, about 35,000 demonstrators poured across the Arlington Memorial Bridge and faced off against 300 U.S. deputy marshals and 6000 armed troops. A clash ensued when the demonstrators attempted to storm the Pentagon, leading to 682 arrests.

News coverage of the My Lai Massacre divided public opinion.

On March 16, 1968, U.S. troops entered the Vietnamese village of Sơn Mỹ, believing—incorrectly—that civilians had left the area and the only remaining villagers were Vietcong guerillas or loyalists. The soldiers then indiscriminately slaughtered as many as 500 civilians, including women, children, and elders.

News of the massacre didn’t go public until several months later, when journalists obtained access to the information that had been gathered through a military investigation. When it did, My Lai made headlines across the country [PDF], local and national newspapers published gruesome photos of the massacre, and repentant soldiers detailed the disaster to reporters including Walter Cronkite. But the coverage divided Americans’ opinions of the conflict, with some defending the officer who ordered the massacre and others horrified by the intensification of the war.

The peace movement encountered violence at the 1968 Democratic National Convention.

One of the most heated confrontations between protestors, politicians, and police occurred during the Democratic National Convention in August 1968, when thousands of anti-war activists, many of them students and people of color, left their assigned areas near the convention hall in downtown Chicago and made for the Conrad Hilton Hotel, where the convention’s leadership had set up headquarters.

Police deployed by Mayor Richard J. Daley—who had fought hard to bring the convention to Chicago and was willing to use force to keep protests in check—met the activists with nightsticks and pepper spray on Michigan Avenue. The violent clash, which left more than 600 protestors and 152 police officers injured and led to the death of one person, became known as the “Battle of Michigan Avenue.”

The Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam marked a tipping point.

The next major demonstration, the Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam, took place from October 15 to November 15, 1969. The protests, motivated in part by anger over the 45,000 American troops and hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese civilians who had already lost their lives in the conflict, collectively mobilized more than 2 million people across the U.S.

Echoing the critical news coverage of the My Lai Massacre, media outlets reported favorably on the demonstrations, emphasizing their orderly conduct and empathetic goals. The Moratorium, more than any other event, marked a tipping point in U.S. politics. Polls showed that six out of every 10 Americans viewed the war as a mistake. The Nixon administration hastened its search for a favorable exit from the war.

The National Guard opened fire on Kent State students.

In April 1970, President Richard Nixon shocked Americans by announcing that U.S. troops were now fighting in Cambodia—a territory just west of Vietnam that the U.S. military had started bombing the previous year. Protests erupted across the country, including one on the campus of Kent State University in Ohio, where National Guard soldiers ended up firing into the gathered crowds. Four students were killed and nine others injured. The tragedy triggered a national student strike that forced hundreds of universities to temporarily close down.

Major musicians wrote the soundtrack to the anti-war movement.

The late 1960s and early ’70s produced some of the greatest rock songs of all time, and many explicitly protested the Vietnam War and its corrosive effect on America’s youth. Joan Baez, Phil Ochs, and scores more musicians directly participated in anti-war demonstrations and expressed their disapproval of the war in their lyrics. From Bob Dylan’s “The Times They are A-Changin’ ” to Malvina Reynolds’s “Napalm,” the Vietnam War era produced protest songs that became huge pop hits. More recently, the Council on Foreign Relations issued a list of the top 20, with Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind” at No. 1 and accompanied by “Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die” by Country Joe & the Fish, Edwin Starr’s “War,” Nina Simone’s “Backlash Blues,” and other classics. Today, many of the genre’s greatest hits remain the go-to anthems of countercultures across the world.

The anti-war and counterculture movements came together at Woodstock.

“We were so anti-war,” Woodstock photographer Henry Diltz told PBS News Hour on the 50th anniversary of that 1969 concert. “Every single person in that half-a-million crowd was against the war in Vietnam.” Held in Bethel, New York, from August 15–18, 1969, the mother of all music festivals cemented the cultural influence of the hippie movement by bringing artists and political activists under the slogan “peace and music.” Young people didn’t just go to Woodstock to have a drug-induced good time, but also to stage a nonviolent protest against the country’s establishment—the same one that had fomented the Vietnam War and killed so many of their peers.

Discover More Stories About the Vietnam War: