Undead children lure families to an abandoned town, where they murder them and drink their blood to sustain themselves. A teenage girl beats another girl to death with a baseball bat in a high-school shower. At a summer camp, a young counselor’s face is ground away on a pottery wheel, leaving behind a ”bloody mass of raw pulp.”

Readers of a certain age won’t be surprised to learn that the above scenarios are taken from the pages of 1990s kid lit: R.L. Stine’s Welcome to Dead House from the Goosebumps series, Christopher Pike’s Die Softly, and Stine’s Fear Street book Lights Out, respectively. By the start of the decade, adult horror fiction was drowning in its own figurative blood. Writers and cover artists were constantly trying to one-up each other in shock value, resulting in an oversaturated market. But if horror has taught us anything, it’s to expect a coda—a final scene where Jason lunges out of the lake, Freddy reaches through the window, or Michael’s supposedly lifeless body has lumbered off to parts unknown. Horror fiction didn’t die when grown-ups stopped buying it; it just slunk off to the children’s section, where it turned the 1990s into a golden age of genuinely frightening kids’ horror literature.

YA Comes of Age

In 1990, young adult (or YA) literature was a relatively new phenomenon. The category is usually traced to the late ’60s, when publishers began in earnest to market books specifically to teen readers. Almost from the beginning, YA lit embraced grim themes such as gang violence (S.E. Hinton’s The Outsiders) and addiction (Robert Lipsyte’s The Contender).

YA fiction, which is typically aimed at readers between the ages of 12 and 18, took a turn into even darker territory in 1974 with Robert Cormier’s The Chocolate War. The book was so controversial that teachers in Panama City, Florida, were placed under police protection after opposing local efforts to ban it from schools.

Cormier’s novel wasn’t a horror story—it’s about a boy who is singled out for increasingly vicious harassment after refusing to sell chocolate for a school fundraising drive—but its blend of disturbing content and anti-authoritarianism helped establish the YA category as a haven for stories that rubbed adults the wrong way.

The Adult Horror Boom

Around the time that YA lit was carving out a place for itself in the American book market, horror literature was finding its footing. At this point, it might be helpful to understand the difference between category and genre, two terms that have very specific meanings in the publishing industry. Genre is a term that describes a book’s content, while category refers to a book’s target audience. Horror and romance are genres; YA, adult, and middle grade are categories.

Horror novels and stories have been around for hundreds of years, but it wasn’t until the late 1960s and early 1970s that publishers were marketing scary stories as horror novels. According to horror writer Grady Hendrix, you can largely credit the horror section of your local bookstore to the publications of three powerhouse novels: Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby in 1967, followed by Thomas Tryon’s The Other and William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist in 1971. Book sales have ebbed and flowed, but horror fiction has been a distinct genre ever since.

The rise of the YA market and the proliferation of horror fiction began to converge by the late 1970s, when authors such as Lois Duncan were writing thrillers and supernatural suspense novels for the teen market. But the kids’ horror boom of the late 20th century still needed one final spark to ignite an explosion. It got just that in 1981 courtesy of Alvin Schwartz, a writer and folklorist who reached into the archives of the Library of Congress and came out with the nightmares that would haunt an entire generation of American children.

Enter Scary Stories

By 1981, Alvin Schwartz, a prolific author of children’s books, had published several volumes of folklore, including 1973’s Witcracks: Jokes and Jests from American Folklore and the following year’s Cross Your Fingers, Spit in Your Hat: Superstitions and Other Beliefs. While sifting through the archives, Schwartz began collecting spooky folktales, urban legends, and ghost stories from oral and written traditions around the world. In 1981, a collection of those stories, accompanied by nightmarish ink-wash illustrations by Stephen Gammell, was published as Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark.

It wasn’t the first collection of truly scary, sometimes disturbing stories aimed at kids—Judith Bauer Stamper’s Tales for the Midnight Hour preceded it by four years. But thanks to its combination of short, compelling stories, Schwartz’s distinctive voice, and Gammell’s nightmare-fuel illustrations, Scary Stories book became a sensation, leading to follow-ups in 1984 and 1991. The books proved that kids could not only handle grisly, genuinely frightening horror stories—they were champing at the bit for more.

Publishers were happy to oblige. With the adult horror publishing boom in full swing and Stephen King in ascent, Dell Publishing launched Twilight: Where Darkness Begins, a line of young adult horror novels by writers such as Betsy Haynes, Richie Tankersley Cusick, and splatterpunk provocateur Richard Laymon, writing as Carl Laymon. Bantam Books countered in 1983 with its Dark Forces line. The series of teen shockers rode the coattails of the decade’s Satanic Panic with cautionary tales about Ouija boards, devilish video games, and sinister heavy metal music.

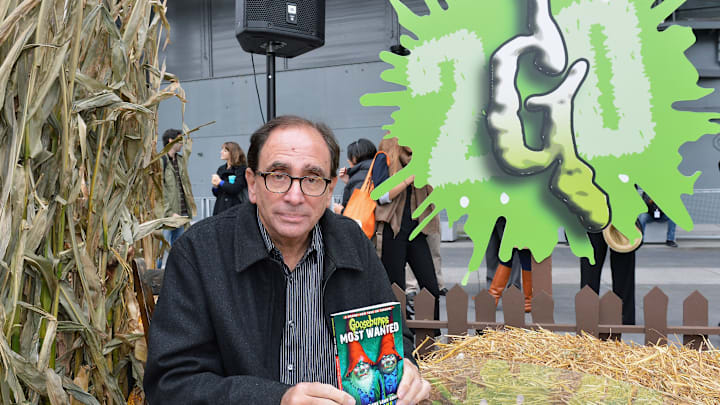

Two years later, the young adult horror market was doing so well that a struggling writer named Kevin Christopher McFadden ditched the adult-oriented mysteries and sci-fi tales he’d been writing in favor of YA horror and suspense. He published 1985’s Slumber Party under the pen name Christopher Pike and never looked back. The next year, a kids’ humor writer named R. L. Stine followed suit, penning a teen horror novel called Blind Date at the behest of an editor. It worked out pretty well for him, and several more YA horror titles followed. Stine closed out the decade with another teen horror milestone: 1989’s The New Girl, the first book in his Fear Street series.

“Forget the funny stuff,” Stine said in a 2015 interview with the Los Angeles Times. “Kids want to be scared.”

Pike ’n’ Stine

By 1991, the adult horror market had played out, a victim of its own excess. In his horror fiction retrospective Paperbacks from Hell, Hendrix writes that publishers had begun to lose money on adult horror titles thanks to a flooded market and a tendency to chase trends—never a formula for success in an industry where it can take years to get a manuscript from a writer’s head to a bookstore endcap. But horror never really dies; it just shapeshifts into new markets, mediums, and subgenres. Adult horror fiction was languishing in the early ’90s, but kids’ horror was thriving, and it was pushing new boundaries in terms of content.

Once the teen horror market was firmly established and writers such as Pike and Stine (sometimes referred to, not exactly charitably, as “Pike ’n’ Stine”) were dominating bestseller lists, middle-grade genre fiction followed suit. The MG horror market caught fire in 1992, when Scholastic, the publisher behind the teen-centric Point Horror series, introduced R.L. Stine’s Goosebumps series with its debut installment, Welcome to Dead House. Aimed at readers aged 8 to 12, Dead House wasn’t the sort of watered-down ghost story parents might expect their kids to read. It was a legitimately creepy tale of undead ghouls who lured entire families to their deaths. The book’s young protagonists survive their ordeal, but not before the family dog is murdered and they face down a horde of zombified town folk.

Scholastic immediately followed up with another Goosebumps installment, Stay Out of the Basement. (Stine’s Fear Street, meanwhile, was still going strong. Just a couple of months after Goosebumps kicked off, he introduced the Fear Street Cheerleaders series with The First Evil.)

“More and more people are jumping on the horror bandwagon,” Barnes & Noble representative Ann Rucker told the syndicated newspaper supplement Kids Today in 1995. “It’s a very in thing now.”

Read More About Children's Books:

Goosebumps became a sales juggernaut. In 1996, Gannett News Service reported that 3.5 million Goosebumps novels were being sold every month in the United States. That year the series accounted for an incredible 15 percent of Scholastic’s $1 billion annual revenue, according to The New York Times. Other publishers answered with their own middle-grade horror titles, including Simon & Schuster’s Christopher Pike-authored Spooksville series and Betsy Haynes’s Bone Chillers.

“Maybe it’s a fad, but I think kids have always loved scary stories,” Haynes told The Miami Herald in 1996. “There’s nothing like getting that little thrill, a little jolt, sitting in your home, knowing it will be all right in the end.”

The ’90s kids horror boom wasn’t restricted to bookstores and libraries. It was a momentous decade for small-screen horror, thanks to innovative series such as The X-Files, Tales from the Crypt, Twin Peaks, and Buffy the Vampire Slayer. In October 1991—months before the first Goosebumps book hit stores—Nickelodeon kicked off its Are You Afraid of the Dark? kids horror series with a pilot episode titled “The Tale of the Twisted Claw,” a reworking of W.W. Jacobs’s classic three-wishes horror story “The Monkey’s Paw.” Fox launched a Goosebumps TV series in 1995, adapting dozens of Stine’s novels and short stories over the course of its original four-year run.

The Horror Ends (Sort of)

While many parents and educators were simply happy to see kids get excited about books, other adults were considerably less enthused. Thanks to their subversive content, the kids’ horror books of the ’90s roused the same force that took on horror comics in the 1940s and ’50s and rock music in the 1980s: adult outrage. The precedent had already been set in the ’80s, when Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark was targeted by conservative activists. Book-banning advocates came for Stine, Pike, and their peers in the ’90s, demanding that the books be restricted to older readers or tossed from library shelves altogether.

In 1993, community watchdog Mildred Kavanaugh wrote to The Olympian demanding that librarians remove some of the more graphic kids’ horror titles from their shelves. Kavanaugh was especially disturbed by Pike’s Monster, singling it out as “vile drivel” and warning that it and similar books could “provoke some young people into self-destruction and violent acts.” Young readers were quick to defend their books—13-year-old Krista Smith fired back at Kavanaugh, suggesting that the would-be moral guardian should “spend her time writing interesting books for kids [her] age instead of complaining about the ones already written”—but they were often fighting a losing battle. The same year, Pike’s Final Friends trilogy was removed from a middle school library in Bothell, Washington, on the grounds that it supposedly promoted “alcohol, euthanasia, and cheating on tests.”

Publishers also committed the same cardinal sin that doomed the adult horror fiction market: They flooded the market. In 1997, The New York Times reported a precipitous drop in Goosebumps sales. Ray Marchuk, Scholastic’s vice president for finance and investor relations, admitted to the outlet that “nontraditional booksellers” such as gas stations and supermarkets were returning large numbers of unsold Goosebumps paperbacks. “As soon as there’s full saturation and they see slowness of sales, they dump it,” Marchuk said.

The original Goosebumps book series officially ended in 1997, but the brand survived thanks to a seemingly endless rollout of spinoffs such as Horrorland and Slappy World. Stine floated other series, including Mostly Ghostly and The Nightmare Room, but none of them gained traction like Goosebumps had. Pike ended the decade with 1999’s The Grave, but a car accident sidelined him for much of the next 10 years; he didn’t write another book until 2010. Other MG and YA horror authors soldiered on, but by the time the 2000s rolled around, kids’ horror had been largely tamed, and young readers were clamoring for a different sort of literary escape: Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone made its American debut via Scholastic in 1998.

Even there, though, Stephen King, saw the ghost of the ’90s kids horror boom. “I have no doubt that Stine’s success was one of the reasons Scholastic took a chance on a young and unknown British writer in the first place,” King wrote for Entertainment Weekly (via Stephen King Fanclub). “[Stine’s] books drew almost no critical attention—to the best of my knowledge, Michiko Kakutani never reviewed Who Killed the Homecoming Queen?—but the kids gave them plenty of attention.”