For students, the summer months represent freedom from the shackles of regimented learning. For educators, they were becoming a problem. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, there was growing concern that children were becoming so captivated by both television and warm weather during their summer vacation that they had abandoned reading altogether. When they returned to school in the fall, their literacy skills had noticeably plummeted.

For a group of broadcasters and teachers, the solution was unusual: Air a new program during the summer months, and use television as a means to get kids excited about opening up a book.

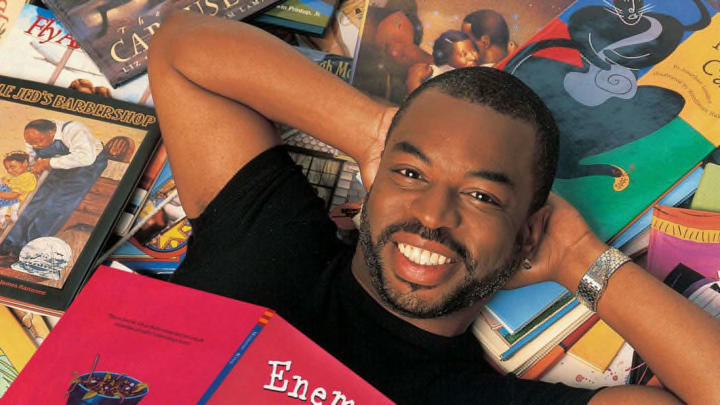

The result was Reading Rainbow, a magazine-style series that celebrated books by reading them out loud to viewers, then exploring their themes in on-location segments. Hosted by LeVar Burton, the show grew from modest trials at PBS affiliate WNED in Buffalo and Great Plains National out of Nebraska. It ran for 150 episodes and 26 years, making it one of the most enduring children’s shows to ever air on public television. If Sesame Street taught kids the alphabet, Reading Rainbow helped them develop a love of words, paragraphs, and narratives.

Despite Rainbow’s altruistic aim, the series was frequently in danger of halting production due to a lack of funds. Lacking merchandisable characters or licensing opportunities that boosted shows like Barney, its producers struggled to convince financiers of its importance. In 2006, succumbing to a changing media and public television landscape, Rainbow shot its final episode. But the show's fans—and Burton—never gave up hope.

With the Reading Rainbow brand once again visible via apps and electronic devices, Mental Floss reached out to several members of the production team to revisit its origins, the approach to the very static practice of reading for the dynamic medium of television, and how Burton didn’t let little things like elephant snot discourage him from helping generations of kids learn to love reading.

In a 1984 survey by the Book Industry Study Group, young adults under 21 years of age were experiencing a marked decline in their interest in reading. In 1978, 75 percent reported they read books. Six years later, the number was down to 63 percent. In Buffalo, New York, and Lincoln, Nebraska, two public television employees grew fixated on how television—long thought to be a thief of a child’s attention—could be repurposed to combat the phenomenon.

Twila Liggett (Co-Creator, Executive Producer): I had been hired by ETV in Nebraska, which distributed programming to classrooms. One day my boss came to me and said, “You know, we’d like to make some television rather than just distribute it.” So I started to think about something in the area of reading.

Cecily Truett (Producer): Putting books on television wasn’t unheard of. Captain Kangaroo had done it. It was Tony Buttino who conceived of the summer loss concept for television.

Tony Buttino (Co-Creator, Executive Producer, Former Director of Educational Services, WNED): I started looking into the summer reading loss phenomenon, which came out of research being done in California. The basic idea was: Kids don’t read during the summer. When they come back to school in the fall, teachers spend two to three weeks bringing them back to their past reading level.

Pam Johnson (Former Vice President, Education and Outreach, WNED): The station would talk to their educational advisors, and what Tony kept hearing from professors, librarians, and teachers was that there needed to be something that explored a love of reading during those summer months. Having that capability early on puts kids on a path to doing well in school.

Larry Lancit (Director, Producer): There was always interest in getting kids to read more, but this was more of a highly-targeted mission. We wanted to make reading fun for kids and encourage them to participate.

Buttino: I started looking at programs that were available to run during the summer. One was called Ride the Reading Rocket, which we aired for a couple of years starting in 1977. I didn’t like the show, but it was something. We’d give out workbooks for classrooms that wanted to use them.

Liggett: There was a lot of stuff made for the classroom then, but it was not that great.

Johnson: Tony went back to 1959, 1960, when WNED first went on the air with live television. You’d have a nun come and read books, or a guy from the zoo come talk about science. It was seeding that notion.

Buttino: After Rocket, I went to see Fred Rogers. He turned us over to David Newell, who played Mr. McFeely on Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, and we shot some short wraparounds with him over the next few summers.

Johnson: WNED would take some preexisting shows and basically use them as experiments. They were all a precursor to Reading Rainbow. It was all building a case for why TV could be good for that kind of thing. WNED was like an incubator.

Liggett: I wanted to do something to mirror what I did in the classroom, which was read to kids out loud, get kids involved in the experience of reading, and have kids talk to each other about reading. Those became the three basic elements of Reading Rainbow.

Buttino: Before Reading Rainbow, we had the Television Library Club. That worked well, but eventually we started thinking, “Well, what kind of show would we make if we had money?”

Lynne Ganek (Writer): The original mission was to create a summer series for inner-city kids who couldn’t go to camp to remain interested in reading. Larry, Cecily, and I sat down and said, “Well, this could be more interesting if we took a different route.”

Buttino: I basically copied some research that had been done for The Electric Company, which showed that if you can get kids in second grade to love to read, it’s a real turning point. Fifth grade might be a little too late.

Liggett: Nebraska's ETV and Great Plains wound up partnering with WNED in Buffalo. Ride the Reading Rocket was not fitting the bill anymore, so I suggested we take my idea and latch it onto the summer reading phenomenon.

Johnson: They compared notes and it really seemed like all roads were leading to the same thing. Different players were having different conceptions of how it might work out.

Ellen Schecter (Writer): The question was: How do you keep kids reading over the summer? There were all these studies showing that reading plummeted, but not solutions.

Ganek: The idea was not to teach kids how to read, but to encourage a love of reading.

Liggett: It was never about sounding out words, but a love of narrative. It was the perfect follow-up for kids who [had moved beyond] Sesame Street. You’d grab them with Sesame Street and then send them on to Reading Rainbow.

Truett: It was Tony who recognized the phenomenon, and Twila who said, “Why not make a TV show about it?”

Liggett: Tony has been known to claim it was his idea, and I take no umbrage at that. Success has many mothers and failure is an orphan.

Buttino: The word “creation” is interesting. I would say I created it, but then Cecily and Twila and Larry came along and recreated it. If I hadn’t done five summers pulling together what was important to the program, I’m not sure how it would have come together.

Ed Wiseman (Producer): What I remember is Ellen Schecter being the heart and soul of the show. Larry and Cecily organized it and put it together. Watching that dynamic with the three of them was wonderful.

With Liggett and Buttino convinced that a show about reading was viable, its execution was left to Cecily Truett and Larry Lancit, a married couple who owned New York City's Lancit Media. Having produced the kids' show Studio See and medical education programming, the couple knew how to navigate informational television with imagination on a budget.

Truett: Tony introduced us to Twila and explained what the goal was, which was to keep kids interested in reading. I thought, “Whoa, how do you do that on television?”

Schecter: We would sit around Cecily and Larry’s apartment at West End Avenue and talk about what kind of show we wanted.

Wiseman: I remember getting a call to come meet with this producing couple who worked out of their apartment. I went there in a three-piece suit, which is what I thought you did. They were so casual and relaxed.

Truett: I answered the door for Ed in a bathrobe.

Ganek: At the time, I was working for WNET in New York. Tony and Cecily hired me to be the associate producer when I was nine months pregnant.

Liggett: Cecily and Larry were responsible for the design of the show. They were and are brilliant producers.

Ganek: Cecily was good about allowing people to speak their mind and doing the same. I’d have an idea and she’d say, “Lynne, that sucks canal water.”

Schecter: An early idea was just to have people sitting around a library, but it was too static and boring. That got shot down.

Liggett: We briefly thought about putting the words on screen and having kids follow along as they were read to. We looked at Zoom. We looked at Sesame Street, of course, the giant of kids' TV. We looked at Mister Rogers.

Ganek: I grew up with Mr. Rogers and even got to know him a little bit later on. He always felt it was important for kids to be spoken to directly by the host. He was a huge supporter of the show.

Truett: We met with Fred, who was a great mentor to us. We wanted to have the kind of relationship Fred had with his audience.

Liggett: The name came from knowing that kids like alliteration and that we wanted to have “reading” in the title.

Buttino: An intern at WNED came up with the name Reading Rainbow.

Ganek: The formula we developed was used for the next 26 years of production, so I think we did something right.

The Corporation for Public Broadcasting agreed to fund roughly half of the first season’s 15 episodes, leaving Liggett to petition corporations for the rest of the $1.6 million budget.

Liggett: It took about 18 months. I became sort of impossible to live with. People were telling me to let it go. My then-husband said, “You love this project more than you love anything else,” implying he was the anything else.

Ganek: Twila was very significant in getting Kellogg’s.

Truett: Twila was a relentless Nebraska girl with a will of steel. She was indomitable.

Liggett: I had written proposals for grants and funding before, but nothing on this scale. My big break came when I asked someone I knew at the University of Nebraska Foundation for assistance. He couldn’t get the money from the school. Then he said, “But I do sit on the Kellogg’s Foundation. I’ll contact the CEO and tell him he should see you.”

Schecter: We were always asking things of people in positions where normally you wouldn’t dare approach them.

Liggett: I went to Kellogg's by myself. How I had the guts, I don’t know. I had enough of the show laid out to convince them it would be a good idea.

Rev. Donald Marbury (Former Associate Director, Children’s and Cultural Programs, CPB): At CPB, we funded about half the budget. That’s the way it works in public broadcasting. There’s nothing PBS can fund in full. We become the initial money to parlay that into leverage to find other granters.

Liggett: Between Kellogg’s and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, we had enough money for 15 episodes. Without Kellogg’s, the show never would’ve gotten off the ground.

Money was only part of the production’s concerns. Without an engaging host, Reading Rainbow was in danger of being passed up by viewers in favor of more exciting programming.

Truett: [The original host was going to be] Jackie Torrance, a highly-regarded storyteller. But we also knew boys were at a greater risk of reading loss and were in need of a good role model. We looked at probably 25 people or so.

Buttino: I wanted the kind of host you’d buy a used car from.

Lancit: We had been thinking about—who was that guy who spoke at the Republican Convention? Scott Baio.

Buttino: I didn’t want a robot. I didn’t want anyone in a costume, someone dressed like a sheepdog or something. I wanted someone sincere. In the proposal, I think I mentioned Bill Cosby.

Ganek: We had gone to a kid’s TV conference and LeVar was there. He was just coming off Roots at the time.

Truett: Lynne said, “Have you seen LeVar lately? He’s so handsome, articulate, magnetic.” We thought, “Gosh, this guy is perfect.”

Schecter: Everyone knew him as Kunta Kinte from Roots. He was so 'live' and expressive.

LeVar Burton (Host): I had done two seasons of a PBS show out of Pittsburgh called Rebop. I had an affection for PBS. It made perfect sense to me, because of the reaction to Roots. You felt the sheer power of the television medium. Over eight nights of television, you experienced the transformation of what we meant when we talk about slavery in this country.

Lancit: I remember Lynne called us and said, “You really need to see this guy. He’ll be on the six o’clock news.” We turned it on and he just had this sharpness about him.

Liggett: Larry sent me a note saying I wouldn’t believe how camera-friendly he was. I saw a thing where he recited poetry on stage for Scholastic high school contest winners and he was so compelling. You could not take your eyes off of him.

Ganek: We decided to get in touch with LeVar, and he agreed to shoot the pilot.

Schecter: Once LeVar said yes, that was it.

Burton: I loved the counter-intuitive idea of it. It was no secret children were spending time in front of the TV set, so let’s go to where they are and take them back to the written word.

Ganek: At the time, LeVar was being managed by Delores Robinson, who was married to Matt Robinson, who played Gordon on Sesame Street.

Liggett: She was a former English teacher.

Truett: Lynne called her when LeVar was doing ABC’s Wide World of Sports on the Zimbabwe River. She said, “He’s not even in the country, but he’ll do it.”

Ganek: [Delores's] heart was in kids' TV and she was instrumental in getting LeVar to do it.

Burton: I was all in. It made perfect sense to me.

Truett: At the time, having an African-American kids' TV host was completely unprecedented.

Marbury: He was the first black host, surely. And more than being an African-American male, he was the first genuine celebrity we had landed for a public broadcasting series.

Burton: It wasn’t on my mind from day one, but it came into my awareness the longer we were on the air. I like to ask what Bill Cosby, Morgan Freeman, Laurence Fishburne, and LeVar Burton have in common: We all worked in children’s television.

Schecter: I’d go over scripts with him and ask how he felt. He really brought a lot of himself into the show, stuff that would relate to him—like how he learned to ride a bike and how scary it was until he realized his father wasn’t holding on to him anymore. That’s a perfect story for kids to hear, and it came off as very genuine because it was.

Wiseman: I would say LeVar on the show was 70 percent him and 30 percent refined for the viewer. He was playing himself, but a character, if that makes sense.

Liggett: The power of LeVar was remarkable.

Truett: No young black men were taking the lead in this kind of show. He was like Fred Rogers, talking directly to the audience.

There was little precedent for Rainbow’s format of focusing on a single book. Out of 600 possibilities for the first season, 67 were selected. While producers assumed publishers would appreciate the free advertising, not all of them fully understood the goal.

Ganek: I’d go to the library and just start pulling out books from the shelves, sit on the floor, and read them.

Schecter: The idea was to pick a book with enough juice to build a show around. If it was about dinosaurs, we’d go dig up dinosaurs at Dinosaur National Park. If it was a book about camping, we’d go camping. We went to film a volcano erupting—anything dynamic to hook kids. To pick out a book, it would have to be something that just jumped off the page and became alive within the context of the show.

Ganek: We wanted something whimsical or serious.

Schecter: When we picked out the books, we went to the National Library Association to make sure the titles we featured would be available when kids went looking for them. If you’re turning a kid on to a book, they have to be able to find it.

Ganek: The first season, we had to pay for the rights to use the books. No one was going to let us use them for free. It wasn’t much, but we had to pay.

Liggett: It was hard. That was why we used mostly unknown authors that first season.

Schecter: I think there was some apprehension over how the books would be presented.

Truett: We went to Macmillan and told someone there we were doing a series about summer reading loss and we’ve got no budget, so could we please have it for free? He was dumbfounded. He said, “I don’t see how this is going to sell any books for Macmillan.”

Liggett: They could not wrap their brain around how we could take the story and stretch it over half an hour.

Truett: I think we paid a few hundred dollars for the first book.

Schecter: Once publishers figured out they’d be on TV, they’d be pretty dumb not to say, “Fine.”

Liggett: We had to negotiate with both the author and the illustrator, since many of them were picture books.

Once a book was chosen, it was up to Lancit Media to figure out how to film its pages while remaining visually interesting.

Ganek: Maintaining the integrity of the artwork in the books was huge.

Liggett: I like to say we were Ken Burns before Ken Burns. We moved the camera across an illustration the same way a child’s eye would move across it, from left to right. That was Cecily’s idea.

Truett: I had been working for Weston Woods, a company that adapted books to slideshows way back when. The kids could see the illustrations rather than have the teacher hold up the book for everyone to look at. We knew we couldn’t be static.

Lancit: We realized early on it would be beyond our budget to do cel animation. We adapted books in what we called an iconographic manner, basically moving the camera on still images. We’d get copies of the books from publishers, cut the pages out, and send them to a company in Kansas that would adapt them by extending characters or adding art in case one of them was cut off by a page. Later, we would do limited animation if it made sense.

Reading Rainbow was divided into three segments: the book recitation, a field trip relating to the content, and a concluding segment where kids reviewed other, similar titles. It was one of the few times children on television had an opportunity to voice their opinions.

Schecter: That was a big thing, to have kids review the books. Kids talking about books didn’t happen often on TV.

Buttino: We found the kids in Buffalo for the first few years.

Johnson: Those were real kids from real neighborhoods in Buffalo. We’d test hundreds and hundreds of them and go, “OK, which one of these 6-year-olds has a presence?”

Ganek: I want to give credit to a librarian I spoke to in New Jersey. She came up with the idea for the kids to do book reviews. She had a little file on her desk where kids had left reviews and said, “Here, you don’t have to take my word for it.” That’s where LeVar’s line came from.

Schecter: I recall I wrote that line and that was my idea to have kids review the books. There would be the main book, and then it would be something like, “If you love this, you’ll love these.”

Truett: That was Ellen Schecter, pure and simple. It found its way into one of the scripts and we thought it would be a nice way to end each show.

Ganek: We found a little girl who was spectacular at doing the review and we were going to use her throughout the entire series. Eventually, we decided to use different kids every time.

Truett: Our research showed kids loved watching kids review the books.

Ganek: We were later accused of coaching the kids, and there was some of that, but it was really in their own words.

With funding and plans in place, shooting for the pilot episode began in early 1983.

Liggett: At first, Kellogg’s said they’d fund us but wanted to see a pilot episode first, which was only reasonable. But essentially, one of the assistants there took me aside and said, “Don’t worry. We love the show. Just go do it.”

Truett: LeVar showed up to shoot in New York City having just gotten off the red eye from Africa. It was 7 a.m. He asked me if he could have a toothbrush and a glass of orange juice.

Burton: I had no time to prepare. Talking directly into the camera and breaking the fourth wall is not something actors do often. I had to learn how to feel like I was very specifically talking to one kid.

Wiseman: He was just so incredibly sincere. I remember shooting that and he was developing his character through the smallest things. He had a backpack, and it was like, “Does he carry that? Does he not? Does he swing it over his shoulder?”

Burton: I just assumed that it was me they were looking for. Over time, I really dialed in the voice of LeVar on Reading Rainbow, and I recognized it as the part of me that either was a 10-year-old or appealed to 10-year-olds. They’re kind of one and the same.

Schecter: We did spring for some animation, where a woman opens a book and this big cloud of activity comes out of it.

Liggett: We contacted the people who had just done an animated Levi’s commercial. We wanted real kids to turn into animated kids. We almost ran out of money just doing that.

Truett: We did take one segment out of the pilot that was a bomb. It was called, “I Used to Think But Now I Know,” which was about first impressions not necessarily being the correct ones. It was a barker.

Lancit: When we took that out, we needed to fill time. We shot footage of a tortoise out in Arizona crawling around. I went to our music guy and said, “Can you get me a tortoise song?” I had no idea what he’d come back with. It was a clever little song. It was just two minutes of this little tortoise.

Ganek: I did have one incident after the pilot. I went to visit Dorothy and Jerome Singer, two professors at Yale who had done work in children’s television and had a column in TV Guide. I really looked up to them and so I brought the Reading Rainbow pilot along with me so they could take a look. They later wrote and told me it was awful and would never go anywhere. So much for academia.

Reading Rainbow premiered July 11, 1983 as the first summertime program funded by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. While it wasn’t the first episode to air, the pilot, featuring the book Gila Monsters Meet You at the Airport, proved to be a memorable introduction to the series for the crew.

Ganek: Someone at the Corporation for Public Broadcasting thought it would be too scary.

Wiseman: The title had “monster” in it, and that led to discussions.

Schecter: Often, self-important people will have ideas about what kids will or will not like. The book was not at all scary.

Truett: One of our advisers had a traumatic experience as a kid because someone brought a Gila monster to her house. It slept in a cage next to her.

Liggett: Our hearts were set on that and we went after it like gangbusters.

Truett: Gila Monsters was perfect because it showed how we would take a book and relate it to a kid’s life, like the fear of moving.

Ganek: I was in the pilot while I was still pregnant, and I remember PBS wasn’t comfortable having a pregnant woman on the show. They shot me from the neck up.

Truett: The response was extremely enthusiastic. We had real Gila monsters on the show. People loved it.

Schecter: The response was extremely positive from the public. It wasn’t like it was with Sesame Street. Older kids were watching it and enjoying it.

Wiseman: It was the most adult-watched kid’s show out there. They’d watch it without their kids.

Liggett: Sometimes we’d be criticized for not picking up the pace, to go faster. But we trusted a kid’s attention to let us take time to get to where we were going.

Not all of the debates surrounded the books. Over time, Burton’s choice of hairstyles and facial grooming would become popular topics of conversation off-camera.

Truett: One of the things we would always have to come to grips with what hairdo LeVar would have in a given year ... There were conversations about his mustache.

Burton: And when I got my ear pierced.

Marbury: We had some wonderful conversations about his haircuts.

Burton: I remember those conversations, and I remember saying, “Look, if you want me, you’ve got to take all of me.” Whether I had a mustache or not, or an earring or not, my authenticity and enthusiasm was coming through.

Wiseman: His hair and style would change from year to year depending on his acting projects. He was partial to a mustache, and the concern was that it aged him. Like, here’s a dad instead of a friend.

Truett: The producer called and said, “Hey, tell him to get rid of that thing.” They wanted more continuity since he didn’t have one in the first season. He shaved, but he was not happy about it.

As Reading Rainbow grew in popularity, publishers and authors began to understand what it could do for their business. Some titles experienced such a surge in sales that books would go back to presses or issue paperback editions to meet the demand.

Burton: The joke was that we would wear kneepads because we were begging publishers to allow us to put their books on television. In the 1980s, TV was still being discussed in academic circles as evil. It was seen as a direct competitor for readers.

Ganek: After the first season, we could barely fit all the books we were getting sent into the office. Publishers would send us practically anything they had.

Wiseman: Boxes came in every day.

Schecter: The whole children’s book business exploded. Some titles went up by 800 percent in sales.

Liggett: Kids would come into libraries asking for books they saw on the show.

Truett: The publishers started making little Reading Rainbow stickers to put on the featured books.

Ganek: The show changed the way children's books were published. They would do very small print runs until Reading Rainbow, and then the numbers got big.

Truett: They finally got it when they saw the show. Reading Rainbow was tied to the sale of thousands of books.

Schecter: Once they saw how carefully we were treating the work and how we were getting celebrities like Lily Tomlin and Meryl Streep to narrate the books, they understood.

Ganek: We had no budget, so anyone you heard reading the stories was doing it because they thought it would be good for kids.

Liggett: Some donated their fee to a charity, and some did it for nothing.

For the second season, Rainbow’s episode count would be cut down to just five installments. Plagued by budget constraints, it would join a number of other public television projects that had problems finding funding. “It’s a very scary time for children’s television,” PBS head of programing Suzanne Weil said at the time.

Liggett: We never did 15 episodes in a season again. It was too hard to raise the money.

Schecter: Money was always a worry. We would get it, but not always in time to keep a steady flow of episodes going. The problem was that we needed a schedule to get shows in production and on the air.

Lancit: Few series get continual funding with no risk. Sometimes we’d be within weeks of putting people on hiatus, then somehow we’d get it going again.

Ganek: Twila was the person responsible for continuing to get money to produce the show.

Truett: Every time we were on the brink of letting everyone go and moving on, Twila would snatch victory from the jaws of defeat. She’d turn people upside-down and shake the money out.

Liggett: It was never guaranteed. One year, I thought we had money for a season and then my contact at Kellogg's went on vacation. The budget got redirected. When she got back, she told me our money was gone.

Schecter: Places like Kellogg’s and CPB didn’t really understand that you needed to keep the production moving. There would be a month or two of waiting, then everyone would have to hurry up.

Marbury: We funded it each and every year. It became a centerpiece for us. It was a marquee value children’s series we just embraced.

Liggett: Barnes & Noble funded us at one time.

Schecter: The questions would always be: How much will they give us? How much can we afford to spend?

Liggett: The National Science Foundation was suggested by a friend of mine. We did science-related books, so it made sense. But after a few years, it’s, “OK, you’ve had your stint here. We can’t fund this show forever.”

Unlike Sesame Street’s large cast of easily-merchandised characters, few elements of Reading Rainbow translated into licensing opportunities, which is one way series can meet their financial needs.

Liggett: We left no stone unturned in an effort to get us licensing deals. A friend set up a meeting with Joan Ganz Cooney, who ran Children’s Television Workshop. She told me, “I can tell you this, you’re not going to make much money selling book bags.”

Truett: We didn’t have the cuddly guys you could take to bed.

Wiseman: The thing that made us special was not having gimmicks, but it also made us less marketable. We didn’t have those licensing dollars flowing back into the show.

Liggett: At one point I wasn’t far from Hallmark in Kansas City. I went over there and thought, “Surely, Hallmark can see their way clear to do something with this.” And their licensing guy basically said, “The problem is, you have these books, but you don’t own these books.”

Truett: Publishers were the largest beneficiaries of the show. We talked about maybe adding a character to the show we could license. We thought about maybe the butterfly from the intro, but that felt very cheesy.

Burton: I was very, very wary of that idea. Thank god we never put it into play. I felt introducing another major character all of a sudden would have a negative impact in how I related to the audience.

Wiseman: I remember in college, a professor was talking about kids' TV, and said that animation and puppets were losing that humanity. LeVar was so sincere. It was back to the Fred Rogers model.

Johnson: We never had LeVar dolls, or ways to leverage those ancillary rights.

Liggett: We never figured it out.

Despite the financial constraints, there was always an allotment set aside for location shooting. In some of the more memorable segments, the show visited a zoo, a Chinatown parade, a live birth, and a high-security prison.

Ganek: Once we settled on a book, we sat down in a circle and talked about what we could do with it. That led to going on field trips depending on what we could afford. We went to a lot of interesting places. We did whitewater rafting in Arizona. We didn’t have money to pay the experts on the show, but when you’re doing work for children, people are very willing to give their time.

Schecter: LeVar was such a good sport. When we did the camping episode, it rained all the time.

Liggett: When he got Star Trek [in 1986], he’d shoot for a week there and then do our show on weekends. Unbelievable stamina.

Burton: I actually thought I was done with Reading Rainbow when I got Star Trek: The Next Generation. I felt I had done it for long enough and it was time to hang them up. They actually started looking for another host. Then Rick Berman, the executive producer on Trek, told me he used to work in children’s programming and had a soft spot in his heart for it. He made sure I could go out and shoot Rainbow when I needed to.

Schecter: I remember LeVar shooting at a zoo and an elephant had a cold and kept blowing snot all over him. He never lost his cool. “OK, let’s try it again.”

Truett: That was hilarious. The elephant was going for the apples LeVar had, and this stream of snot was coming from its trunk.

Burton: My whole thing was to not interrupt the flow of conversation with the viewer. That’s sometimes difficult to do when you’ve got elephant snot on you. I had goats trying to eat my clothes.

Truett: We pulled him out of a goat pen before he got pummeled to death.

Wiseman: I remember shooting near a live volcano. We left our editor about a mile from the eruption.

Liggett: We did an episode on the Starship bridge. Patrick Stewart remains one of the most courteous people I have ever met.

Truett: The biggest mistake Trek made was covering up [LeVar's] eyes with that device. People knew him from Trek, but on our show, he was talking directly to the audience.

Ganek: The biggest, and really only, arguments we’d have would be where to go on location. Someone would ask, “Where do they have the best dinosaur collection?” Someone thought it was Pittsburgh, and someone else would say otherwise.

Schecter: Chinatown [in Manhattan] was a problem. We did Liang and the Magic Paintbrush there, but it was not easy. There are gangs there and you have to be on the right side of them. We managed to ingratiate ourselves.

Truett: As time went on, we delved into more mature topics. We talked about the Underground Railroad, about slavery. We did Badger’s Parting Gifts, about losing someone you love when they die.

Wiseman: We filmed in Sing-Sing, in parts where cameras had never been allowed before. We pushed the envelope in quiet ways. We live-filmed the birth of a baby! We choreographed it with an OB/GYN and a mom. It had never been done in children’s TV before.

Lancit: We coordinated it with a doctor and didn’t show anything graphic. It was all above the waist.

Wiseman: Every PBS station aired it but one: WNET in New York, of all places.

As Rainbow rolled on, it drew considerable attention from libraries, publishers, and the television industry itself, taking home 26 Emmys for excellence in children’s programming.

Wiseman: People at the Daytime Emmys would look at us sideways. “Here come the Reading Rainbow people.” I think we won in just about every category.

Buttino: That was always wonderful, to dress up and attend those shows.

Wiseman: During the 2003 Emmys, LeVar went on stage to accept and said, “This might be the last time we’re up here. There’s no funding.” And we wound up getting funded because he said that on TV.

Burton: I don't remember that, but it sounds like something I would do. Year in and year out, we continued to stay afloat despite a continuous need for funds. I think Reading Rainbow always had a guardian angel that was looking out for us.

Lancit: I always said we had Reading Rainbow karma. Whatever we needed, we would eventually wind up getting. People were always willing to help.

In 2006, Reading Rainbow had seemingly run out of goodwill. The culprit: the No Child Left Behind Act, which placed restrictions on how the Corporation for Public Broadcasting could allocate funds.

Wiseman: We just kind of always thought there would be more money, that Twila would find a way to get it. Like, this show is too good to just die.

Liggett: We ran out of money in 2006 and did our last show in 2006.

Truett: Part of it was the gradual move to other shows. Even though parents wanted their kids watching PBS, they’d leave the room and the kids would go back to Mighty Morphin’ Power Rangers.

Liggett: To this day, I’m bemused by the funding issues we had. Everyone is obviously in support of reading and literacy—until you start asking for money.

Ganek: Encouraging a child to want to read was our downfall in some ways. No Child Left Behind wanted kids to be taught the mechanics.

Burton: No Child Left Behind was the death knell. The money was marked for the rudiments of reading. There was no mandate for encouraging a love of reading. All the sources we had come to depend on were no longer able to help us.

Liggett: The mechanics of it would make your toes curl, but basically, CPB got ready-to-learn funds and then shows would come in and plead their case. I argued. I can’t tell you how hard I argued.

Marbury: There were greater demands from Congress to venture out into other areas. We had to start questioning how much we put into the series year after year.

Truett: PBS had to justify its existence to political constituencies. The programming choice for a lot of public television became animation. Stuff like Blue’s Clues.

Burton: We shot our last episode in 2006 but weren’t pulled from the lineup until 2009. After three seasons with no new content, we were pretty much canceled.

Although the show aired in reruns through 2009, Burton was adamant that Rainbow not be forgotten. In 2012, he and partner Mark Wolfe launched an iPad app that capitalized on interactivity and the digital age of entertainment. In 2014, their Kickstarter campaign raised more than $6 million to become the most-funded project in that site’s history.

Burton: When it was taken off the air, it was like a light bulb moment for me. “Wait a minute. There’s something I can do.” We spent most of 2010 and 2011 gathering the rights that had been scattered to the winds and throwing a rope around them to make a deal with WNED.

Wiseman: It was, at the time, the biggest Kickstarter ever, with $6 million. That shows you the power this show had.

Burton: It held the record for the biggest number of backers. It was pretty overwhelming, seeing the depth of passion and enthusiasm for the brand.

Schecter: I thought it was kind of strange. LeVar owns Reading Rainbow? How could this be?

Burton: There was an opportunity to raise seed capital and hire a team.

Liggett: My understanding is that WNED made a deal with the University of Nebraska, and that LeVar and his company made a broad licensing arrangement with WNED, but WNED still owns it.

Truett: I’m thrilled LeVar is keeping the legacy of Reading Rainbow alive.

Buttino: I’m not sure LeVar and WNED are getting along too well right now. I think WNED sold some stuff to him and they’re not happy about it. [WNED and RRKidz are currently involved in litigation concerning the Reading Rainbow license, with WNED accusing RRKidz of “illegally and methodically” trying to “take over” the brand by pursuing projects that were not part of their original agreement.]

Burton: There’s nothing I can say about it right now. I hope and believe we’ll get it resolved soon.

Today, Reading Rainbow remains a touchstone children’s television series, its impact on both viewers and its production team immeasurable. Burton's RRKidz continues to reach children via apps and other online iterations of the series.

Ganek: The cast and crew of Reading Rainbow loved each other.

Wiseman: If we had a crew member come in and say, “It’s just a kids' show, it doesn’t matter,” they’d be gone. It was because it was a children’s show that it had to be the best.

Truett: We started out as kids ourselves, really, and grew up over 26 years.

Wiseman: I married Orly [Berger, a fellow producer]. Our kids wound up appearing on the show.

Liggett: We made kids want to read, and that makes a huge impact. It’s like playing the piano. The more you do it, the better you get.

Truett: It was one of the first shows that shined a light on books and literacy, of enjoying books and enjoying books with your kids.

Johnson: PBS would commission surveys, and over an 18-year period, teachers reported Reading Rainbow was the most-used video in their classrooms. They saw it not only as a reading show, but as a way for disadvantaged kids to see things they might not otherwise get exposed to. They can see a bee farm, or a live volcano.

Wiseman: People will talk about the show with tears in their eyes.

Marbury: I’d put it up there with Sesame Street. I really would, in terms of undergirding the cruciality of reading to our young people.

Burton: Part of the secret sauce of Reading Rainbow was tying literature to a real-world experience. I cannot tell you how many people I have met who told me they became a writer or librarian or bee keeper or were inspired by the show to some degree or another and that it had a major impact on their life.

Ganek: So many people today do their own version of the Reading Rainbow theme song on YouTube. I saw Jimmy Fallon dressed as Jim Morrison from The Doors doing it on his show with The Roots.

Liggett: People will sing the theme song to me.

Marbury: I could sing it right now! Butterfly high in the sky, I can go twice as high …

Buttino: Friends will say I was involved with Reading Rainbow at restaurants. Waiters will come up to me and show me the theme song is their ring tone. It happens all the time.

Lancit: I think there was a purity in the way we presented the program that reached kids and touched them in a way where they didn’t feel patronized. We spoke to them at a level that made them feel confident. That I had something to do with giving a generation of kids that feeling is a wonderful thing.

Truett: I believe in my heart that the relationship LeVar created with young people was one of the factors in bringing them to embrace a relationship with an African-American man. It changed a generation’s perspective.

Wiseman: He made color both an issue and not an issue at the same time. LeVar transcended race, gender, and age.

Burton: That’s something emotional about that sweet spot of childhood, and Reading Rainbow triggers that for people. It was during a much simpler time in their lives. The world is a lot faster now.

Marbury: I don’t think enough children’s programming has followed Reading Rainbow’s lead. There is nothing more important in education than reading. We must continue to make it foundational to the educational process.

Schecter: Sometimes I’ll meet friends of my kids who go, “You wrote Reading Rainbow? That was my favorite show. I’d get a book, close my bedroom door, and let my imagination go.” That’s what we wanted.

Burton: It was very pastoral. We allowed that conversation with the audience to breathe. I think that’s part of the appeal. I felt they believed they had a friend. Someone who was rooting for them, that knew and cared about them. And that was real.

All images courtesy of RRKidz unless otherwise credited.