Medical scientists and engineers have developed a palm-sized model of the female reproductive system—a step toward a future in which doctors can see how their patients’ bodies would respond to drugs before they even write a prescription. The researchers described their progress today in the journal Nature Communications.

This “’menstrual cycle in a dish” is the latest in a series of “tissue on a chip” projects being developed around the world. The “chip” in question is a small vessel, like a computer chip, on which researchers construct tiny working models of human organs and tissue using real biological materials. A well-built organ on a chip functions like the real thing, reacting to drugs, pathogens, and other stimuli—like a lab mouse, but better, and less ethically complicated.

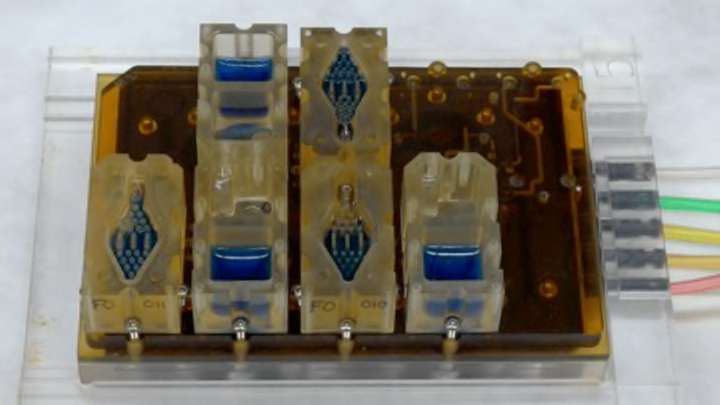

The new technology, called EVATAR, is a little tray containing miniature 3D models of the uterus, ovaries, vagina, fallopian tubes, cervix, and liver, all connected by fine tubes filled with a blood-like fluid. The organ models secrete hormones and interact with one another just like organs in a real body.

Lead researcher Teresa Woodruff of the Women's Health Research Institute at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine called EVATAR “nothing short of a revolutionary technology.”

In a statement she explained how future cubes and other chips could be customized for each patient. "If I had your stem cells and created a heart, liver, lung and an ovary, I could test 10 different drugs at 10 different doses on you and say, 'Here's the drug that will help your Alzheimer's or Parkinson's or diabetes,'" Woodruff said. "It's the ultimate personalized medicine."

Research on the female body has long lagged behind that of males, in part because female organisms of all kinds have been underrepresented in laboratory and clinical research. Only recently has the imbalance begun to be corrected, as major funding bodies like the National Institutes of Health pass rules requiring experiments to consider equal numbers of male and female subjects.

To have an entire complex female reproductive system in the tissue-on-a-chip mix is, therefore, no small accomplishment, but it is an important one.

Coauthor Joanna Burdette of the University of Illinois at Chicago says EVATAR will be useful for studying illnesses like endometriosis, fibroids, and cervical cancer.

"All of these diseases are hormonally driven, and we really don't know how to treat them except for surgery," she said. "This system will enable us to study what causes these diseases and how to treat them."