After months of production delays and millions of dollars spent covering budget overruns, the film editors working on the "4D" Disney theme park attraction dubbed Captain EO began to get frantic feedback from company executives who had seen some of the film's early footage: Michael Jackson was grabbing his crotch way too often.

The star of EO, Jackson was just three years removed from one of the biggest albums in music history, 1982’s Thriller. Disney had approached him with the idea of helping to create an exclusive, ambitious film with in-theater effects like fog and lasers that could be experienced only in Disney-branded theme parks. With the assistance of George Lucas, the production had created a 17-minute space musical, nearly seven minutes of which featured Jackson performing while frequently putting his hands in places Disney would never approve of.

The footage was zoomed, edited, or clipped to remove the gestures. But a bigger problem remained: Would enough people show up to justify Disney’s $20 million investment—on a per-minute basis, the most expensive film ever made at the time?

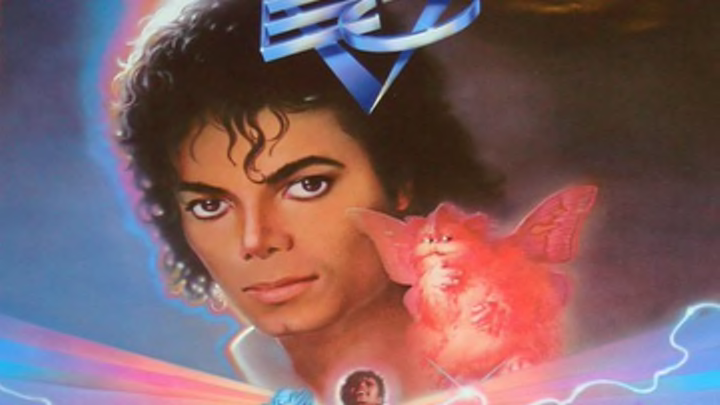

Meredith P. via Flickr // CC BY-ND 2.0

The Disney of today is a monolithic enterprise, one that seems to be able to print money as quickly and easily as the U.S. Treasury. They own a sizable portion of pop culture’s most appealing brands—Marvel, Pixar, Star Wars—and reap billions from merchandising and films.

But the Disney of the 1980s was operating under markedly different circumstances. It would be years before their animated films experienced a resurgence, first with 1989's The Little Mermaid, and decades before they began to acquire other character libraries. One of their largest assets of the era was their theme park division—Disney World in Orlando, Florida, and Disneyland in Anaheim, California, with a satellite park in Tokyo and one planned for Paris. The continued success of those parks was crucial to their business as a whole.

In 1984, newly installed Disney CEO Michael Eisner decided to pursue an attraction that would blend Disney’s resources in both live entertainment and film. His idea was to approach Michael Jackson, a recording artist who was arguably the most famous entertainer in the world at the time. Jackson’s second solo album, Thriller, had been released in two years prior and went on to sell 30 million copies in the U.S. alone. With director John Landis, he had proven himself to be a master of the music video form with an elaborate mini-movie of the title track. Most importantly, Jackson was a tremendous fan of Disney, often visiting their parks in disguise so he could enjoy the rides without being solicited by fans. He traveled there so often he bought his own private suite at Disney World.

Eisner asked Jackson if he’d be interested in appearing in a short film shot in 3D and accompanied by lights, smoke, lasers, and other sensory effects that would be accomplished live in the theater. He also assured Jackson that the production would be overseen by George Lucas, the filmmaker behind Star Wars, who had a working relationship with Eisner thanks to the numerous park attractions based on his space saga.

Jackson was enthusiastic for two reasons: He loved Disney, and he was eager to explore acting. He agreed to star in the project and provide the original music if Eisner could convince Steven Spielberg to direct it.

Eisner couldn’t; Spielberg’s schedule didn’t allow for it. But he and Lucas did enlist Francis Ford Coppola, the Oscar-winning director of the Godfather films. While Coppola didn't usually go for elaborate, effects-heavy fantasy flicks, he and Lucas were close friends; he also perceived EO to be a possible way of rebounding from various setbacks he had suffered early in the decade. Films like The Cotton Club had put his production company, American Zoetrope, in financial turbulence.

With Lucas, Coppola, and Jackson in place, four of Disney’s brainstorming Imagineer employees were asked to come up with a premise that incorporated music, outer space, and 3D effects. The result was The Intergalactic Music Man, a parable about an interstellar performer who can "heal" distressed civilizations with song. That morphed into Space Knights, which kept the weaponized music angle but was less of a fantasy.

After the Imagineers pitched Eisner, Lucas, and Jackson, the story settled into a kind of space saga that would feature Jackson as the captain of a starship that harbored alien life forms, including a flatulent, elephant-snouted creature named Hooter. When they crash-land on a planet ruled by an evil queen, Jackson’s performance art helps to break her influence over the population. It was Coppola who suggested the title be changed to Captain EO, after the Greek word eos, or "dawn."

Captain EO began production in the summer of 1985 and was conceived as a 12-minute film with a budget of $11 million. As the production dragged on, it became apparent that was an absurdly optimistic figure. Disney believed Lucas would help keep the film on schedule, but his work prepping Howard the Duck and various Lucasfilm projects meant he only checked in periodically. Coppola and his director of photography also had no experience shooting footage in 3D, which required deliberate lighting and camera set-ups. Learning on the job led to overruns, which Disney executive Jeffrey Katzenberg tried to control. But Coppola found an ally in Lucas, who wasn't involved in day-to-day decisions but backed extravagant spending on things like the installation of a giant gimbal that could shake the spaceship set on command.

The problem grew larger after principal photography had finished. The planned 40 effects shots grew to 140; editors spent time avoiding Jackson making any dance gestures parents visiting the park would find objectionable; the Magic Eye Theater, which was being constructed to incorporate the live effects, suffered from delays. Executives even toyed with modulating Jackson’s speaking voice, since they considered it too high-pitched. (Since no one wanted to confront the issue with Jackson directly, the concern was dropped.)

Originally planned for a spring 1986 launch, EO was pushed to September. In the industry, the soaring budget, nine-month post-production schedule, and number of high-ranking entertainment names involved led to a new working title. In Hollywood, the lavish effects film was being referred to as "Captain Ego."

Getty

With a minimum of $20 million spent on the production, there was little point in sparing any expense for the premiere of Captain EO on September 13, 1986. Disney hosted a screening at Epcot Center in Orlando, inviting the film’s stars and other celebrities. Anjelica Huston, who played the Supreme Leader in the film, rode in a motorcade with her then-partner Jack Nicholson and waved to park guests; Lucas put in an appearance. Jackson’s sisters La Toya and Janet were also photographed at the event, along with Dolph Lundgren and O.J. Simpson.

Curiously, Jackson himself was nowhere to be found. Eisner joked he was probably there in disguise "as an old lady"—something Jackson had actually done at one point in order to meet with the Imagineering team without drawing attention. But the more likely explanation was that Jackson had been embarrassed by the reaction to pictures of him sleeping in a hyperbaric chamber, a publicity stunt he had orchestrated earlier that week that had gotten negative attention.

If the crowd was bummed by Jackson’s absence, they didn’t take it out on the film. Using fog machines, twin 70 mm film projectors, and 3D glasses for dramatic effect, EO debuted to hugely positive reviews from those in attendance and grossed an estimated $2 million its first weekend, confirming Eisner’s theory that original theme park attractions would help populate their front gates. In one poll, 93 percent of attendees listed EO as a main reason for wanting to visit.

Captain EO ran at Epcot until 1994 and in Anaheim until 1997, when it was replaced by a Honey, I Shrunk the Kids attraction. In 2010, the Disney parks revived the film following the outpouring of sentiment that accompanied Jackson’s death the previous summer. It ran until December 2015, at which point Disney announced it would be closing the attraction for good.