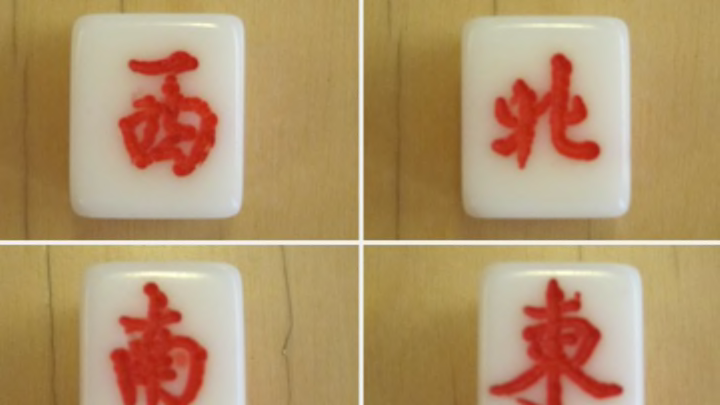

People have found some weird things inside walls over the years, from mummified babies to outrageously rare artwork. Other times, remodeling projects reveal nothing but mouse carcasses or a bunch of dust. This mah-jongg tile, found inside the wall of a former tenement building in New York City, might not seem fascinating at first. But it has an interesting story to tell about the many waves of immigrants that surged into New York during the 20th century.

The piece was found during a historical restoration project inside 103 Orchard Street, a building on New York’s Lower East Side that is owned by the Tenement Museum. The tile emerged when workers sifted through the debris in the building’s third floor. Just one of many unexpected artifacts found inside the building’s walls, it’s an example of the kind of object historians love—a little slice of everyday life.

Though the address 103 Orchard has remained the same since the building was first constructed in 1888, the building and the neighborhood itself changed dramatically over the years. Around the time the building went up, the neighborhood was home to Italian and Jewish immigrants, followed by waves of Puerto Rican immigrants and then Chinese immigrants. Over the years, over 10,000 people lived inside the building’s 15 apartments, a testament to the flows of United States immigration in the 20th century.

You might think that the piece belonged to a family like the Wongs, Chinese Americans who lived in one of the apartments inside 103 Orchard starting in the late 1960s. But it could also have been owned by one of the Jewish families who lived inside the apartment building.

The mystery of the mah–jongg piece reflects the enigma of mah–jongg itself. It’s not exactly clear when the game was invented, or even how it’s properly spelled. (Merriam-Webster prefers mah-jongg.) What is certain is that after gaining popularity in China it came to the United States alongside Chinese immigrants in the 1920s. Despite harsh anti-Chinese laws that essentially banned Chinese immigration, many Chinese people risked deportation and came to the U.S. anyway, sporting false ID papers and, apparently, some mah–jongg sets.

As the game became more popular, it started to show up in department stores like Abercrombie & Fitch. The future purveyor of apparel for shirtless male models (which has been around since 1892) was the first U.S. company to offer the game, importing and selling over 40,000 sets in a single decade.

Fred Astaire and his sister Adele playing mah-jongg in 1926. Image credit: Getty Images

Mah–jongg also became a beloved game among Jewish women. For a while, the game was so popular that you could find mah-jongg books, magazines, clubs, and merchandise seemingly everywhere. Scholars believe that the game not only reflects globalization and immigration, but appealed to Jewish immigrant women as a way to build and keep social networks.

Though primarily played by wealthy and suburban Jewish women, it was popular enough that it very well could have been adopted in tenements, too. The days of mah-jongg–related movies and even ballets is long gone, but it’s actually become more popular in recent years, especially among younger Jewish women eager to learn the game their grandmas loved.

Whether the piece was owned by Chinese or Jewish immigrants, it shows how pastimes and traditions can cross-pollinate—and how a single building can contain remnants of multi-layered histories. And if you want to explore 103 Orchard for yourself, you’ll get a chance this summer, when the Tenement Museum opens a new exhibit there.