Chicago Bears wide receiver Willie Gault liked to correct anyone who insinuated that his team’s record, “The Super Bowl Shuffle,” was an act of hubris. After all, it was recorded a full six weeks prior to the Bears gaining entry into the 1986 Super Bowl; two players even declined to appear in the accompanying music video, fearing some sort of karmic reprisal.

“If you listen to the record, it doesn't say we're going to the Super Bowl,” Gault told the Chicago Tribune. “We didn't say we were going to win the Super Bowl. It said we were going to do a dance, and it's the Super Bowl Shuffle.”

Collaborating with nine other teammates, the Gault-led rap was a recording industry anomaly. It was a novelty song performed by athletes that fans both in and out of Chicago found entertaining. More than 700,000 copies of the single were sold, and 170,000 videotapes were moved in its first year of release. Rather than have egg on their face, the Bears wound up winning the Super Bowl.

Unfortunately, their moonlighting session would have an unforeseen consequence. Declaring their goal to “feed the needy” in an early verse, the profits were supposed to go to charitable causes in the Chicago area. It proved to be a lot more complicated than that.

The Shuffle was born out of Gault’s interest in stardom outside of football; he wanted a career in acting or music. In 1985, Gault was introduced to Richard Meyer, owner of Chicago's Red Label Records. After Gault appeared in a video for one of his artists, Meyer told him it might be fun to record something with the entire Bears team—bringing with them a built-in level of awareness that would help bolster Meyer’s new label.

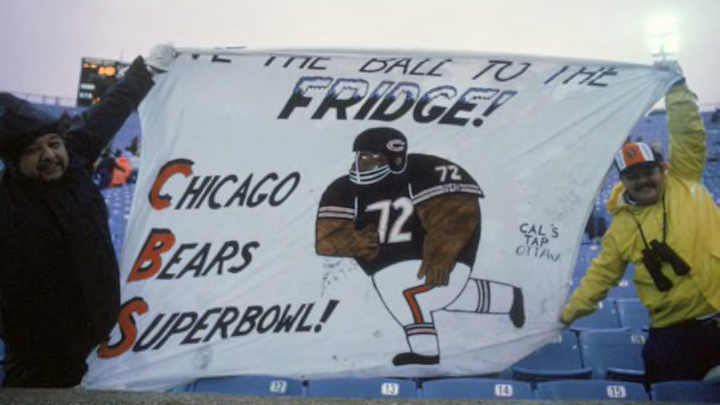

Gault liked the idea and floated it around the locker room on the premise that profits would go toward area charities. Walter Payton, who was once in a band, loved the premise; others, like William “The Refrigerator” Perry, were already doing commercial spots and didn’t mind poking fun at themselves. Only Dan Hampton refused. He thought it was presumptuous and would come off poorly.

Meyer had a songwriter rework a title named “The Kingfish Shuffle” after an old Amos 'n Andy radio series character, personalizing lines for each of the 10 players who agreed to have speaking parts. “The Super Bowl Shuffle” was recorded within a week, over two sessions, during which a gleeful Payton ran around pinching the other players' hamstrings.

Naturally, every radio station in Chicago found airtime for it. The song was so successful both in and out of the team’s area that it eventually made it to #41 on Billboard’s Top 100 chart. Emboldened, Meyer arranged for the team to film a music video to accompany the song.

Dan Hampton may have been on to something: The night before they were scheduled to film the video, the Bears dropped their first game of the season to the Miami Dolphins. It was a 38-24 drubbing, and the team showed up for filming the following morning, December 3, in a foul mood. Payton, who was initially supportive of the project, was so dejected he refused to appear until weeks later. (They spliced his footage in.)

Incredibly, the VHS copy of the video moved so many units it threatened to unseat Michael Jackson’s Thriller on sales charts. In February of 1986, the song was nominated for a Grammy for Best Rhythm & Blues Vocal Performance by a Duo or Group. (It lost to Prince & the Revolution's "Kiss.") Best of all, the Bears’s victory at Super Bowl XX was, at the time, the highest-rated in the game’s history. What started as a glorified joke had become a lucrative venture.

Just how lucrative would quickly become an issue for Illinois’s attorney general.

Gault and Meyer had succeeded in orchestrating an unlikely hit, but they did fumble one detail: No one had checked in with the head office of the Chicago Bears to see if “The Super Bowl Shuffle” had their official blessing.

The ownership wasn’t entirely amused. The song did seem boastful, Gault’s protests aside, and they were concerned about exactly how this proclamation to “feed the needy” was going to go. If an NFL team made a public announcement that funds were pending, then the Bears wanted to know when and how much.

They contacted Illinois Attorney General Neil Hartigan, asking if 50 percent would be a permissible amount of the proceeds to donate. Hartigan’s office responded that 75 percent was the letter of the law; Red Label was thinking more along the lines of 15 percent.

The accounting dragged on through 1987, with Red Label claiming album returns needed to be calculated before they could estimate profit. Middle linebacker Mike Singletary threw his gold record in the garbage in frustration at the delay, saying that, "It doesn't represent an accomplishment. It doesn't mean a thing unless it gets food to the hungry people who were supposed to be fed out of it. I thought it was a clean-cut deal. It's taken a year."

Eventually, $331,000 was liberated from an escrow account and turned over to the Chicago Community Trust for distribution. The 10 players with speaking parts made $6000 apiece, and all donated their salaries to contribute an additional $60,000.

That $6000 would later become a sticking point for six players (including Gault), who filed a lawsuit in 2014 claiming they hadn’t received additional payments from the lucrative merchandising and distribution of the video for non-charitable causes. Meyer’s daughter, Julia, is currently the owner of the "Shuffle" and remains vigilant about its availability on streaming sites.

While the Shuffle ultimately had a net positive outcome, it’s worth noting that the song’s success had some unfortunate consequences. On the heels of the video’s popularity, a number of pro sports teams recorded some terrible tracks of their own, including the Los Angeles Dodgers, Dallas Cowboys, and Los Angeles Rams, who recorded a single titled “Ram It” with the help of Meyer.

“No charities are involved,” Meyer said.