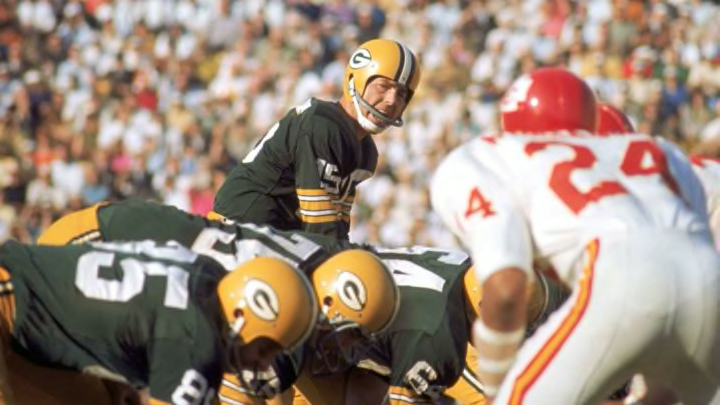

In 1966, two football leagues were vying for gridiron dominance: the venerable NFL and the sport's newcomer, the AFL. On June 8, 1966, the two leagues announced their plans to merge, rather than compete over players and a split fan base. This meant a new championship game had to be conceived that would determine which was the dominant league every year. Today we know it as the Super Bowl—one of the most polished, extravagant events of the entire year. But on January 15, 1967, when the first AFL-NFL World Championship Game took place, it was something bordering on a disaster, with television mishaps, a dispute over the name, and thousands of empty seats marring the very first Super Bowl Sunday. To see how the big game nearly fell apart, here are eight facts about the first Super Bowl.

1. At first, the game was only casually known as the Super Bowl.

In 1966, meetings were going on about the first-ever championship game between the NFL and the upstart AFL set to be played in January of that next year. In addition to talking about location and logistics, the big question on everyone’s mind was what to call it. Though Pete Rozelle, the NFL’s commissioner at the time, suggested names like The Big One and The Pro Bowl (which was the same name as the NFL’s own all-star game), it was eventually decided that the game would be called … the AFL-NFL World Championship Game.

A name like that just doesn’t create much buzz, though, and the newly merged league needed something punchier. Then, according to History, Lamar Hunt, owner of the Kansas City Chiefs, recalled a toy his children played with, a Super Ball, which led to his idea: the Super Bowl.

The name picked up support from fans and the media, but Rozelle hated it, viewing the word “Super” as too informal. By the time the game began, the tickets read “AFL-NFL World Championship Game,” but people were still offhandedly referring to it as the Super Bowl. By the fourth year, the league caved and finally printed Super Bowl on the game's tickets. For Super Bowl V, the Roman numerals made their debut and stayed there every year except Super Bowl 50 in 2016. (The first three championship games have also been officially renamed Super Bowls retroactively.)

2. The first Super Bowl aired on two networks.

Since the first Super Bowl involved two completely different organizations, there was a bit of an issue televising the game. NBC had the rights to air AFL games, while CBS was the longtime rights holder for the NFL product. Neither station was going to miss out on its respective league’s championship game, so the first Super Bowl was the only one to be simulcast on two different networks. Rival networks also meant rival announcing teams: CBS used their familiar roster of play-by-play man Ray Scott in the first half, Jack Whitaker in the second half, and Frank Gifford doing color commentary for the entire game. Curt Gowdy and Paul Christman led the voices for NBC.

It turns out the competition between the two networks for ratings superiority was just as intense as the helmet-rattling game played on the field. Tensions were so high leading up to gameday that a fence had to be built in between the CBS and NBC production trucks to keep everyone separate. The more familiar NFL broadcast team over on CBS won the ratings war that day, beating NBC’s feed by just a bit over 2 million viewers.

3. Super Bowl I didn't even come close to selling out.

The cheapest price for a Super Bowl LVI ticket—which will take place on February 13, 2022—is currently hovering around $6400 after fees, but frankly, you could probably charge people double that and the game would still be a guaranteed sellout. The first Super Bowl, however, didn’t quite have that same cachet behind it. With tickets averaging around $12, the AFL-NFL World Championship Game couldn’t manage to sell out the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum in 1967. It’s still the only Super Bowl not to fill up its venue.

Despite blacking the game out on TV stations within 75 miles of the Coliseum to get fans to the stadium rather than watching at home, about a third of the stadium’s seats were empty. Some fans balked at the steep $12 ticket prices, while others were so incensed at the blackout that they stayed away out of protest. Whatever the reason, the sight of tens of thousands of empty seats for what was supposed to be the most important game in both leagues’ history was not what Rozelle had in mind when the Super Bowl was conceived.

4. Different balls and different rules were used.

The overall product between the AFL and NFL wasn’t that different, but there were a few hiccups when making the rules fair for both teams. The AFL’s two-point conversion rule, which it used for the entirety of its existence, was barred from the game, allowing only the traditional point-after field goal instead. When the AFL and NFL later merged, the two-point conversion was banished altogether until 1994, when it was reinstated league-wide.

The other big change for the game was the ball itself. The AFL used a ball made by Spalding, which was slightly longer, narrower, and had a tackier surface than the NFL’s ball, which was created by Wilson. To make each team feel at home, their own league’s ball would be used whenever they were on offense.

5. Super Bowl I's second-half kickoff had to be redone because the camera missed it.

When the second half of Super Bowl I began, everyone was ready for the kickoff: players, refs, and the production crew. Well, one production crew was ready, anyway. It turns out NBC missed the opening kickoff of the second half because the network was too busy airing an interview with Bob Hope. The kickoff had to be redone for the sake of nearly half the TV audience; even worse, some poor soul probably had to break the news to Packers coach Vince Lombardi.

6. The First-ever halftime show featured two dudes in jetpacks.

Forget your Maroon 5, Travis Scott, and Big Boi performances; Super Bowl I’s halftime show was an affront to gravity itself as two men in what can only be described as jetpacks (though technically they were called “rocket belts”) flew around the field to give people a glimpse at what the future of slightly above-ground travel would look like. Very little video exists of the spectacle today, but this performance was later revisited at the halftime show for Super Bowl XIX, when jetpacks made their long-awaited return to gridiron absurdity.

In addition to its airborne theatrics, the inaugural show also included some marching bands and the release of hundreds of pigeons into the air—one of which dropped a present right on the typewriter of a young Brent Musburger.

7. The original Super Bowl I broadcast footage was lost for decades.

Unlike today, where games are DVR’ed, saved, edited into YouTube clips, and preserved for all eternity, there is no complete copy of the broadcast edition of Super Bowl I. Both CBS and NBC erased the footage decades ago, likely as a cost-saving measure. Then, in 2005, a man named Troy Haupt found a copy of the CBS broadcast in his attic, which had been recorded by his father on two-inch quadruplex tapes. (However, the halftime show and parts of the third quarter are missing.) The footage has been digitally restored and is currently in a vault at The Paley Center for Media in Manhattan. The tapes had been in legal limbo for years, as Haupt and the NFL couldn't come to an agreement on ownership and payments for the footage. But in 2019, the NFL and the Paley Center screened the footage to mark the 100th season of the league, with the center noting that Haupt had donated the tapes to them.

8. The NFL tried—and failed—to show the game in some form in 2016.

Perhaps as a way to show Haupt that they didn’t need his tapes, the NFL Network released a version of the game cobbled together not from CBS or NBC footage, but from video edited together from its then-nascent NFL Films division. With the game’s radio call played over it, every play from the game was aired in 2016, albeit not how it was originally seen in 1967. Unfortunately, the game also featured some questionable running commentary from the NFL Network’s current analysts during the entire broadcast. The re-broadcast was such a disaster that the NFL Network had to re-re-broadcast it without the intrusive commentary from its own analysts.

A version of this article was originally published in 2017; it has been updated for 2022.