The story of slavery in the United States is one of brutality, splintered families, and erasure. For many descendants of enslaved people, genealogies and other family histories can break down, severed by the missing links that resulted when families were broken up and sold to separate masters. An artifact in the Smithsonian’s new National Museum of African American History and Culture preserves a tiny attempt to fight back against that erasure. It’s known as “Ashley’s sack."

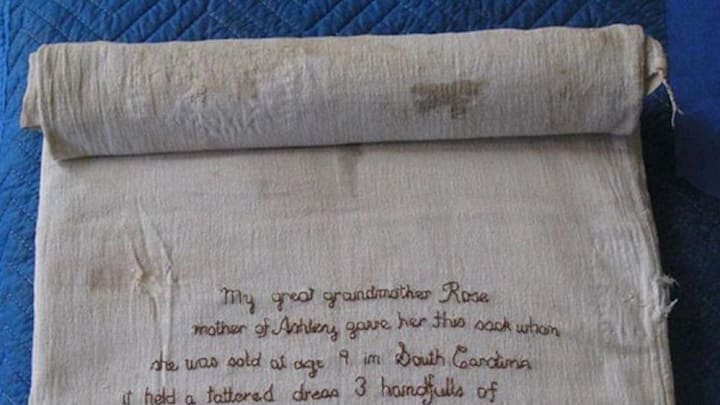

The unbleached cotton sack is the canvas for 56 words of embroidery—words with a tragic tale to tell. “My great grandmother Rose mother of Ashley gave her this sack when she was sold at age 9 in South Carolina,” it reads. “It held a tattered dress 3 handfulls of pecans a braid of Roses hair. Told her It be filled with my Love always she never saw her again Ashley is my grandmother Ruth Middleton 1921.”

The story of Rose, Ashley, and Ruth was common among millions of enslaved African Americans. It's been estimated that one-quarter of all enslaved people who crossed the Atlantic were children, and 48 percent were put to work before they turned 7 years old. Though slaves did manage to form family units, those families were generally disregarded by masters, who viewed them as chattel. Thus, slaves always ran the risk of being separated from their families—even children as young as 9-year-old Ashley.

When the sack—incredibly rare to have survived both slavery and the centuries—was purchased at a flea market in Tennessee in 2007, its origins were murky. As the Associated Press reports, the woman who discovered the sack realized it was valuable, but decided not to sell it on eBay. After some online research, she determined that the sack might have been connected to Middleton Place, a South Carolina plantation that is now a National Historic Landmark and museum and where African Americans were once enslaved. Museum officials purchased the sack and put it on display.

Reactions to the powerful story told on the bag were immediate and complex. Some volunteers felt overwhelmed or uncomfortable discussing the object. “Some volunteer guides complained that the sack, and the powerful reactions it engendered, distracted from the core mission of the tour: to highlight the wealth, political leadership, and cosmopolitanism of the white Middletons,” writes anthropologist historian Mark Auslander.

Intrigued by the bag, Auslander set out on a quest to discover the identity of Rose, Ashley, and Ruth. He used slavery records as well as bank, court, and census data to research the women. But he faced a number of obstacles: slave records often involve mass sales of unnamed women and children, many records have been destroyed, and Rose was a very common name for enslaved women.

The name Ashley, however, was not. His answers aren't definitive, but Auslander did find intriguing evidence of a child named Ashley owned by a South Carolina planter named Robert Martin in the 1850s, who also owned a woman named Rose. Using 1920 census records, Auslander was also able to find an African-African woman named Ruth Middleton who had family roots in South Carolina, and who died in Philadelphia in 1988. Her possessions likely ended up being given away, which is how the sack found its way to the flea market, Auslander theorizes.

No matter how the bag got to that flea market, it's near-priceless evidence of what slavery did to families and what they suffered both together and apart. Middleton House lent the bag to the NMAAHC, where it—and its story—is now displayed across from a block used in slave auctions.

[h/t: KUOW]