Saint Hildegard of Bingen was a smasher of stained-glass ceilings. From traumatic beginnings, she fought and flourished, becoming one of the most accomplished and enduring authors, artists, healers, composers, and visionaries of the Middle Ages.

THE TITHE

Hildegard was born in 1098 to noble parents in West Franconia, now part of Germany. At the age of three, she is said to have experienced her first vision of dazzling, divine light. A strange and sickly child, within a few years her parents had passed her off to the church. After all, devout Christians were obligated to tithe, or give the church one-tenth of all they owned—and Hildegard, by many accounts, was their tenth child.

By the time Hildegard was eight, her parents had delivered her to the monastery at Disibodenberg. There, she was assigned to serve a young noblewoman named Jutta von Sponheim. Jutta was not content simply to pray; she wanted to be literally buried in religion. She dressed herself in rags, moved into a tiny cell, and brought Hildegard with her. Then she told the monks to wall them in. Jutta had sealed herself, and her charge, within a living tomb, becoming what was known as an anchoress. For the next three decades, the two would receive all of their food, water, and contact with the outside world through a small window.

THE SCRIBE

As Jutta’s behavior became more and more fanatical, Hildegard prayed harder and studied more. She learned to read and write, and a sympathetic monk brought her books on botany and medicine and pushed them through the cell’s small window. Hildegard devoured them. Jutta continued to deteriorate and undertook long fasts that left her weakened. More noble families delivered their daughters to the cell inside the wall; like Hildegard’s parents, they considered it a duty to donate their daughters—along with substantial sums of money—to the church. Left with no alternative, Hildegard took them under her wing.

After Jutta’s death in 1136, Hildegard was named magistra (spiritual teacher) of the growing flock. She continued to read and develop her love of music and words. Then she began to make her own. A voice in a vision instructed her to “tell and write”—and so Hildegard did. She began composing sacred music.

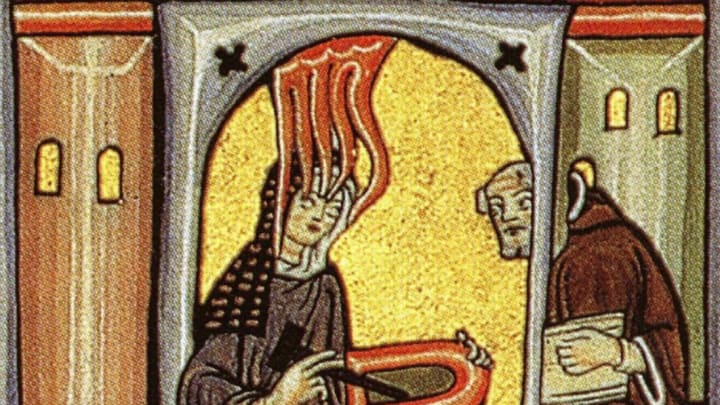

She recorded her visions and the prophecies of her angelic visitors. She described and drew the plants she saw in the monastery courtyard and their medicinal properties. She illustrated religious texts with luminous images from her dreams. And she began to object to the corrupt monks who would imprison children for the sake of the dowries that came with them.

The universe. Image credit: The Yorck Project via Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

As Hildegard’s voice on the page grew stronger, so did the threat she presented to the monks who held her and her charges captive. Word of her healing and prophetic abilities had spread, bringing visitors, ailing supplicants, and devotees. But women weren’t supposed to write or publish books. They weren’t supposed to talk to God, or heal the sick, or write hymns. And they definitely weren’t supposed to criticize the church. On their own, each of these crimes looked bad. Viewed all at once, they looked a lot like heresy.

THE FIREBRAND

Hildegard was not oblivious to the risks of her nonconformity. She knew the best way to protect herself would be to obtain the blessing of higher church authorities, and so in 1147 she wrote to the supportive abbot Bernard of Clairvaux for aid. Clairvaux in turn interceded on her behalf with Pope Eugenius III, who endorsed and encouraged her. Hildegard responded with her thanks—and an exhortation for him to try harder to reform his church.

By this time, Hildegard had become unpopular in the Disibodenberg monastery. And the place became more hostile than ever after her conversation with the Pope. So when a holy voice told her to take her charges and escape to a ruined monastery near Bingen, she did not argue. Monastery leaders attempted to stop her, but Hildegard fell suddenly and violently ill—a sign, some said, that God was angry the monks had interfered. Hildegard recovered and told her flock to prepare for their journey.

THE ABBESS

The magistra and her new religious order reached their new home at Bingen around 1150. A new vision inspired Hildegard to dress her brides of heaven not in Jutta’s self-congratulatory rags, but in fine cloth and tiaras.

Over the next two decades, she would tour the country to preach. She would publish treatises on the natural world, including plants, animals, and stones. She would write a handbook of diseases and their cures. She would invent languages and words and imaginary lands. All this her detractors begrudgingly allowed.

But the final straw came in 1178 when Hildegard and her nuns respectfully and knowingly buried a man who had been excommunicated from the church before his death. The convent was stripped of its rights. There could be no Mass, no sacraments, and no music.

Hildegard fought and argued and pled. Finally, in March of 1179, the interdict was lifted.

THE LEGEND

Her legacy secure, Hildegard could, at last, rest. She died in September 1179 at the age of 81, leaving behind a wealth of sacred music, writings, and teachings that are still widely read and enjoyed today. Her work has enjoyed particular popularity since the late 20th century, when her mysticism and the feminist elements of her life and work gained new attention in part from a burgeoning New Age movement.

She was canonized in 2012 by Pope Benedict XVI, who called her "perennially relevant" and "an authentic teacher of theology and a profound scholar.”