It’s a Victorian mystery Sherlock Holmes himself couldn’t have passed up: A tangled case of stolen identity made possible by a deadly shipwreck, complete with wealth, a baronetcy, and fabulous estates at stake. Thought it was one of the most celebrated legal cases of the 19th century, the intriguing tale of the Tichborne Claimant has been all but forgotten today.

THE BACKGROUND

Born into wealth, given an impressive education, and raised in Paris, Roger Tichborne was a worldly man. On April 20, 1854, at age 25, Tichborne finished up a tour of South America and boarded the Bella, a ship headed from Rio De Janeiro to Jamaica. Four days later, its wreckage was found off the Brazilian coast, devoid of any survivors.

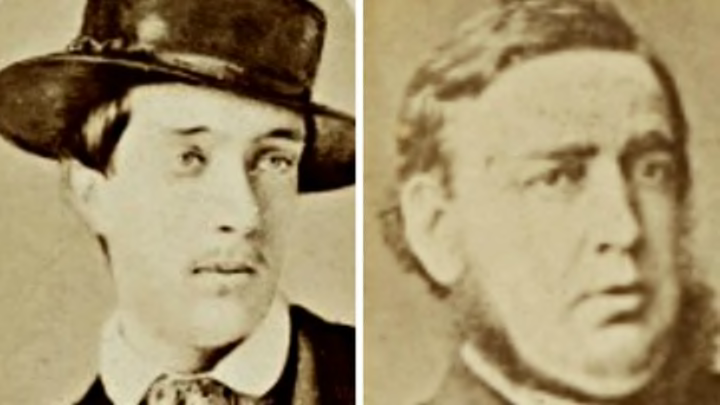

Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

Sir James Tichborne, Roger's father, passed away in June 1862, which would have made Roger the 11th Baronet of Tichborne, if he'd been alive. Instead, the title passed to his younger brother Alfred. Perhaps realizing that young Alfred, a man known for his dissolute habits, was not the best choice to head up the family finances, Lady Tichborne contacted a clairvoyant, who assured her that her eldest son was alive and well.

THE DISCOVERY

In addition to the seer’s declaration, rumors swirled that survivors of the Bella wreck had been picked up by a passing ship and dropped off in Australia. Between the rumors and the clairvoyant's report, Lady Tichborne came to believe that her son was still alive, and she was determined to find him. She took out newspaper advertisements, offering “a handsome reward” to anyone who could provide information.

Sydney Morning Herald // Public Domain

After expanding her search to Australian newspapers, Lady Tichborne received her first clue in October 1865, over 10 years after her son's disappearance. During a bankruptcy examination, a butcher named Thomas Castro from Wagga Wagga, Australia, had revealed some interesting information, including the fact that he had survived a shipwreck and owned properties in England. He also happened to smoke a pipe engraved with the initials RCT—Roger's initials.

Pressed by the lawyer (who had seen the newspaper advertisements), Castro admitted that he was, indeed, the long-lost baronet, and began communicating with Lady Tichborne. Though he was a bit cagey about answering certain questions, she became convinced the butcher was her son. Some experts think Lady Tichborne may have been particularly eager to believe that Roger had survived after Alfred drank himself to death in 1866.

Castro/Tichborne, or “the claimant,” as he was often referred to in 19th century accounts, said that after the Bella had sunk, he'd been rescued by a ship called the Osprey, which was bound for Melbourne. Afterward, he'd wandered Australia and eventually took up life in Wagga Wagga as a butcher. His reasons for staying in Australia and not contacting his family remained unclear.

After communicating with Lady Tichborne, the claimant moved to Sydney to make plans to return to England, including borrowing travel money under the strength of the Tichborne name. At the urging of the lawyer who "discovered" him, the butcher also wrote a will, which raised a few eyebrows. It wasn’t the act itself that was surprising, but some of the contents within: He mentioned family properties that didn’t exist and referred to his mother as “Hannah Frances” when her name was Henrietta.

While the claimant was in Sydney, he happened to run into two former Tichborne family servants, men that had known Roger well. Both of them believed the claimant was Roger, though one of them quickly recanted after “Roger” badgered him for money.

Identifying the man wasn’t exactly straightforward—if it was Roger, he had gained quite a bit of weight. Before he left for South America, Tichborne had been very thin. When the servants ran into him more than a decade later, he was up to nearly 200 pounds. He put on an additional 20 during his time in Sydney and gained another 40 pounds by the time he arrived back in England on Christmas Day 1866. By 1871, the claimant was nearly 400 pounds. While some believed that he was merely enjoying being a man of means once again, others wondered if he was trying to purposely obscure his appearance.

THE REUNION

Upon his arrival in England, the claimant tried to call on Lady Tichborne, but found she was away in Paris. Next, he went to East London and inquired after a family named Orton. They, too, were unavailable, having moved away from the area entirely. He told a neighbor that he was friends with Arthur Orton, who, he mentioned, was now one of the richest men in Australia.

When the claimant eventually reunited with his mother, she immediately proclaimed him her son and gave him a monthly allowance of £1000. However, Lady Tichborne was practically alone in her acceptance of the man. A few family acquaintances were in the claimant’s corner, including a family doctor who claimed he saw a physical resemblance. Also helping his case was the fact that he remembered small details from his childhood, such as a fly fishing tackle he liked to use, specific clothing he used to wear, and the name of a family dog.

But there were also things working against him. His correspondence with his mother was full of misspellings and grammatical errors, though Roger had been extremely well educated. And the claimant lacked a French accent or even an understanding of the language, both of which Roger had, since he was raised largely in Paris. He didn’t recognize his father’s handwriting, and couldn’t remember anything about the boarding college he went to. Also, before Roger left for South America, he left a package with a family servant. The claimant wasn’t able to describe what was in the package.

Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

Of course, he explained all this away by claiming that the shipwreck had been extremely traumatic, scrambling his memory and affecting him in other mysterious ways. And even with all of those suspicious issues, Lady Tichborne believed in the claimant, so there was little that anyone could do about it. Then in 1868 she died, eliminating his only advocate and costing him emotional and financial support.

THE TRIALS

In May 1871, the claimant was part of a civil trial that required him to prove that he was, indeed, Roger Tichborne. Investigators had done plenty of digging on him over the years in Australia, and had found a plethora of people who identified him as Arthur Orton, the son of a butcher from Wapping, London, who had made his way to Australia to make a living and at some point taken the name of Tom Castro. The prosecutors theorized that when Lady Tichborne’s advertisements were published in Australia, Orton saw an opportunity to improve his standing in life. The servants he happened upon in Sydney may have provided pertinent details about Roger's life in exchange for money or the promise of money.

At the trial, the claimant avoided answering questions about his relationship with Arthur Orton and denied that they were one and the same. The prosecution was prepared to call in more than 200 witnesses to argue the point, but in the end, it turned out that Tichborne had tattoos the claimant didn’t possess.

The jury rejected the suit, but a criminal trial now had to be held to determine if the claimant was guilty of perjury. The resulting trial ended up being the longest ever in English court, lasting 188 court days. The evidence against the claimant was abundant, including testimony from a handwriting expert who said that the claimant’s penmanship matched Orton’s, not Tichborne’s. Another damning piece of evidence: While a ship called the Osprey had, indeed, arrived in Australia, it didn’t match the claimant's description. Furthermore, he couldn’t name the crew members or captain, and ship logs didn’t mention picking up shipwreck survivors—an event that probably would have been noteworthy enough to jot down.

It took the jury just half an hour to find the mystery man guilty; he ended up serving 10 years of a 14-year prison sentence. In all that time, he only admitted that he was Arthur Orton once—and it was because a journalist paid him for the confession. Once he had the money, the claimant immediately retracted the statement and went back to asserting that he was Roger Tichborne, even though he no longer sought the money, fame, or properties associated with the name.

THE CONCLUSION

When he died in 1898—fittingly, perhaps, on April Fool’s Day—the claimant was buried as a pauper. However, in a confusing move, the Tichborne family allowed a plaque to be placed on the coffin identifying the man within as “Sir Roger Charles Doughty Tichborne.” The same name was also listed on the death certificate, and registered with the cemetery burial records.

More than a century later, we still don't definitively know the fate of Roger Tichborne—and unless the family consents to DNA testing, we probably never will.

[h/t: Futility Closet]