Last month, paleontologists announced a new species of ancient pinniped—a group that includes modern seals, sea lions, and walruses. The animal lived off the coast of what is now Washington state about 10 million years ago and probably fished like seals do, relying on the power of its oversized eyes to track its prey. Robert Boessenecker, an adjunct lecturer who works for College of Charleston’s department of geology and environmental sciences, recently presented a study on the newfound fossil at the annual Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting in Salt Lake City.

Discovered in Washington’s Grays Harbor County in the 1980s, the incomplete skeleton consists of neck vertebrae, a well-preserved ribcage, a partial sternum, and a skull with jawbones. It was encased in exceptionally hard rock that took scientists prepping the fossil two decades to clear away. Judging by the available remains, the animal was more than 8 feet long—about the size of an adult male California sea lion.

Boessenecker coauthored the study with paleontologists Tom Deméré of the San Diego Museum of Natural History and Morgan Churchill of the New York Institute of Technology. Together, they were able to classify the creature as a new species of Allodesmus, a pinniped genus whose members once roamed coastal Japan and North America’s western seaboard. Although a species name has been chosen for the animal, it has yet to be made public. “We plan on naming [it] after a beloved colleague who has contributed extensively to pinniped paleontology,” Boessenecker tells mental_floss. “But we’re going to keep that under wraps for now.”

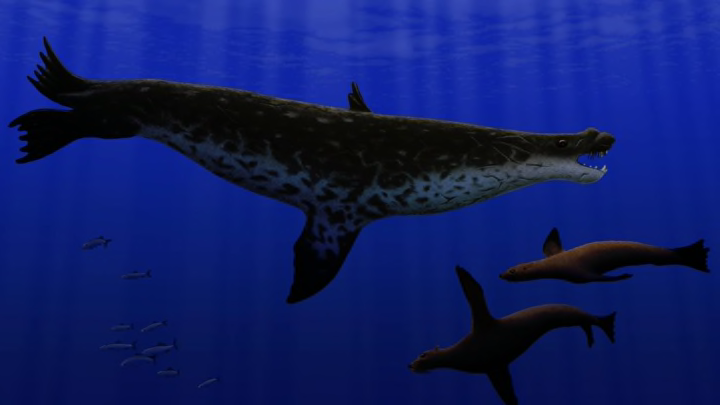

The newly discovered animal hailed from a marine mammal family known as the desmatophocids, which evolved around 23 million years ago. From the neck down, they looked very much like today’s seals and walruses, both of which sport a combination of enlarged front flippers and well-developed hind limbs. But the skulls contained a mix of features seen in a variety of pinnipeds today—and some evidence suggests that they had trunk-like noses similar to modern elephant seals.

Notably, the new Allodesmus also features proportionally huge eye sockets, each of which could house a poolroom eight ball. Their dimensions suggest it had exceptionally keen eyesight, allowing the animal to function as a deep-diving predator. Because the ocean gets darker the farther you get from the surface, the size of its eyes would have allowed it to absorb large quantities of light far beneath the waves. While navigating through the inky depths, it would’ve most likely hunted down such game as fish and squid.

Boessenecker’s team closely studied the skeleton to see what they could learn about its life. With the exception of some seals, most pinnipeds are strongly sexually dimorphic: Their relative body size, in other words, makes it easy to distinguish their gender. Fossil evidence reveals that the same was true of this Allodesmus species; the skeleton’s size and the thickness of its canines suggest it was male.

It’s also obvious that the Grays Harbor specimen was nibbled on after it died. “Fossil dogfish teeth were found around the skeleton of our Allodesmus, and numerous bite marks are present [as well],” Boessenecker says. Then, as now, a marine mammal’s corpse must’ve looked like an irresistible banquet to the ocean’s many opportunists.

At about 10 million years old, the animal is the youngest-known desmatophocid specimen on record. Its relative youth may reveal quite a bit about the evolution and ultimate disappearance of this pinniped group. “Truth is, we have no idea why desmatophocids died out,” Boessenecker says. “Perhaps our new species was in a very specialized niche, surviving as long as possible [until it was] eventually snuffed out, a possibility that remains for our most charismatic extant pinniped."

To Boessenecker, the "most charismatic extant pinniped" is the walrus. In fact, the rise of walruses might have been a factor in the disappearance of pinnipeds like the Grays Harbor animal, because they may have gradually outcompeted Allodesmus and its kin between 13 and 8 million years ago. Back then, the walrus family was a large and diverse group whose members included such oddballs as the four-tusked, mollusk-eating Gomphotaria pugnax. But today, there’s only one remaining species of walrus—and it’s currently at risk of becoming endangered. Boessenecker and his team hope that by learning more about the Grays Harbor Allodesmus, we’ll be able to better understand and protect pinnipeds today.