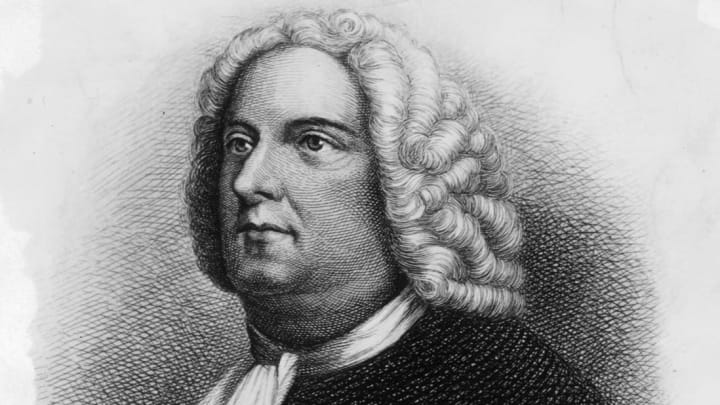

In 1681, William Penn wrote that Pennsylvania—a colony he’d just obtained via royal charter—would one day become “the seed of a nation.” He couldn’t have possibly known how prophetic this statement was. Penn remains a beloved figure in the Keystone State and throughout the country. Here are a few things you might not have known about him.

1. HE HAD A FAMOUS FATHER.

William Penn was the son of English Admiral Sir William Penn (1621-1670). The seaman, a national hero, took a circuitous path to fame and knighthood. When King Charles I was beheaded for treason in 1649, Penn senior initially supported the anti-monarchical Commonwealth government that replaced the deposed ruler. However, when it became clear that this republican experiment would fail, he helped restore the dead king’s exiled son, Charles II, to the throne in 1660. Admiral Penn quickly won the royal family’s esteem and became a trusted advisor of Charles’s brother, James, who served as the Duke of York and ran the English navy.

2. HE WAS EXPELLED FROM OXFORD.

One day around 1655, a prominent Quaker named Thomas Loe was invited to the Penn residence in Ireland. The man preached his faith with incredible fervor, at one point moving the Admiral to tears. It was an experience that would change the course of the younger William Penn’s life. Although he didn’t adopt Quakerism right away, the boy instantly became sympathetic to the movement.

Those sentiments got him into trouble after he enrolled at Oxford’s Christ Church College in 1660. There, Penn met John Owen, a former dean who’d been dismissed by the school because of his radical calls for religious tolerance. Barred from teaching on campus, Owen started organizing private courses at his own home. Penn soon became a regular at the ex-Dean’s classes. These sessions convinced the teenager that many Oxford policies were horrendously unjust.

A particular bone of contention for Penn was the school’s insistence that all students—regardless of their personal beliefs—attend a mandatory Anglican service every Sunday. Penn defiantly sat out. He also violated Oxford’s dress code, which required pupils to wear surplices, a type of religious garment. Instead, Penn wore simple clothes, drawing the ire of school officials. Fed up with his rebellious behavior, Oxford expelled him in 1662. Admiral Penn didn’t react well to this development; according to some sources, he punished the teen with a beating.

3. PENN’S RELIGIOUS VIEWS LANDED HIM IN JAIL ON SEVERAL OCCASIONS.

After his dismissal from Oxford, Penn studied theology at the College of Saumur in France and then attended Lincoln’s Inn, a well-regarded London law school. In 1666, his father sent him to supervise the family estates, where he reconnected with Loe. The preacher’s sermons struck a familiar chord with the youth, and Penn began attending Quaker meetings. On September 3, 1667, Penn was present at a gathering in Cork, Ireland that was broken up by the police. Wrongly accused of plotting to incite a religious riot, the Quakers were imprisoned. By virtue of his social class, Penn alone was offered a pardon—which he refused on principle, demanding instead that he receive the same punishment as his peers. Penn was released shortly thereafter and formally converted to Quakerism later that year. He never looked back.

Penn again found himself incarcerated in 1668. Shortly before his second arrest, Penn had written and distributed a revolutionary pamphlet titled The Sandy Foundation Shaken. In it, he denied the widespread belief that the Holy Trinity consisted of “three separate persons.” Since this was a crime at the time, he was jailed inside the Tower of London, where the troublemaker remained for eight months. Behind bars, Penn clarified his theological views by writing two new treatises: Innocency With Her Open Face and No Cross, No Crown. Penn’s father is believed to have petitioned the Duke of York to bring an end to this prison term, and William Penn the younger was freed months later.

But his troubles with the law were only just beginning. In the early 1660s, the English Parliament enacted new measures that would become the bane of Penn’s existence. First came the “Quaker Act of 1662,” which prohibited Quakers and other religious minorities from worshiping in groups of five or more. Then, in 1664, the Conventicle Act took things a step further, outlawing all non-Anglican religious assemblies. A year later, the infamous Five Mile Act—which forbade traveling “nonconformist” preachers (such as those who backed Quakerism) from coming within five miles of where they had served as minister—was passed.

In 1670, Penn conducted an illegal Quaker meeting in London and was charged with violating the Conventicle Act. He and one of his associates were jailed for two weeks before a jury acquitted them. But the jury was heavily punished for refusing to hand down a conviction as the judge was demanding. They were held without food or water, fined, and several members of the jury were sent to Newgate Prison. (This case is credited with the modern concept of an independent jury.)

But nothing could dissuade Penn from attending these gatherings or preaching Quaker doctrines. He was arrested yet again in February 1671 and sent to Newgate Prison without a trial. He continued to produce political and theological essays right up until his release in August.

4. PENN WAS PUT IN CHARGE OF A NEW WORLD COLONY BECAUSE KING CHARLES II WAS INDEBTED TO HIS FATHER.

Throughout his life, Admiral Penn loaned a large sum of money to the crown. As the years went by, interest on this small fortune accumulated. By 1680—10 years after Admiral Penn's death—King Charles II found himself £16,000 in debt to the Penn family. That’s when the younger Penn cooked up an inspired solution. In May 1680, he petitioned the King for a grant of land in America, specifically the wilds that lay between Maryland and present-day western New York. In exchange, he’d forgive the monarch’s debts. Charles II took him up on the offer, and on March 4, 1681, Penn was given the charter for what later became known as Pennsylvania.

5. HE DIDN’T COIN THE NAME “PENNSYLVANIA.”

Originally, Penn wanted to call it New Wales, due to the hilly terrain which reminded him of the Welsh countryside. However, a Welsh-born secretary in England’s Privy Council took issue with this, forcing Penn to reconsider. His next suggestion was Sylvania, after the Latin word for forest. The Council then chose to tweak this new name a bit by adding the prefix “Penn” in an attempt to honor the late Admiral, William Penn’s father. At first, William Penn disapproved of the moniker and even tried bribing two undersecretaries to change it. When this failed, he resignedly gave up the fight, lest his protests be misconstrued as an act of vanity.

6. HIS FAMOUS PEACE TREATY IS SHROUDED IN MYSTERY.

The Quaker first set sail for the colony that bore his family name on August 30, 1682. Of course, long before it meant anything to him, the area had been home to countless generations of Leni Lenape Native Americans. So before his departure, Penn was advised by the Bishop of London to contact these indigenous people and begin negotiating for some land on which to establish a city. Accordingly, in 1681, he dispatched an olive branch in the form of a letter which was read to Lenape leaders by a translator. “I desire to enjoy [Pennsylvania] with your love and consent, that we may always live together as neighbors and friends,” it read. Later on in this document, he denounces the “unkindness and injustice that hath been too much exercised towards you by the people of these parts of the world.”

Upon arriving in Pennsylvania, Penn apparently impressed the locals by acquiring some Lenape language skills so that, in his own words, he “might not want an interpreter on any occasion.” At some point in either 1682 or 1683, Penn visited Shackamaxon, a Lenape village on the Delaware River. There, he purchased much of the land upon which Philadelphia now sits. This exchange has gone down in history as the “Great Treaty.” Immortalized by the 1772 Benjamin West oil painting William Penn’s Treaty with the Indians, the event remains a point of pride for the City of Brotherly Love. In 1764, the French philosopher Voltaire paid tribute to the deal, writing “This is the only treaty between [American Indians] and the Christians which has not been sworn to, and which has not been broken.”

Was Voltaire exaggerating? If so, to what extent did he embellish or oversimplify reality? Unfortunately, we’ll never know for sure. No firsthand accounts of this meeting were written down, and the generally agreed-upon details about what actually happened all come from oral histories passed along from generation to generation. According to many of them, a huge elm tree that once stood in Philly’s Kensington neighborhood marked the original gathering site. Dubbed the Treaty Elm, it was knocked over by violent winds in March 1810. Close examination of the rings suggested that the plant would have been well over a century old by the time Penn allegedly met with the Lenape beneath it. Surrounding land was converted into historic Penn Treaty Park in 1894.

7. HE ENVISIONED PENNSYLVANIA AS A “HOLY EXPERIMENT.”

In his colony, Penn set out to create a safe haven for Quakers and other religious minorities, who would all—ideally—be granted freedom of worship. He often described the master plan as a “Holy Experiment.” To entice his fellow Europeans into buying up Pennsylvania real estate, Penn distributed pamphlets advertising the place’s merits in English, French, Dutch, and German. Privately, he hoped that the revenue obtained from settlers would help pull him out of financial debt. “Though I desire to extend religious freedom,” Penn once wrote, “… I want some recompense for my trouble.” His efforts paid off: By the year 1685, he’d sold 600 tracts of land that collectively represented 700,000 acres.

Under Penn, the future Keystone State became the only English colony to refrain from establishing an official church. This was in keeping with his personal belief that “Religion and policy … are two distinct things, have two different ends, and may be fully prosecuted without respect one to the other.” Pennsylvanians were thus afforded the right to freely practice whatever faith they chose—at least, ostensibly. It is worth noting, however, that the colony’s original constitution didn’t allow non-Christians (or Catholics) to vote or hold public office.

8. HE PLAYED A MAJOR ROLE IN PENNSYLVANIA’S FIRST WITCH INVESTIGATION.

In 1684, two Swedish-born settlers living in present-day Delaware County were brought before a Philadelphia Superior Court for allegedly bewitching a neighbor’s cow, which was said to have given very little milk as a result. Penn perhaps wanted to prevent the kind of mass hysteria that would soon descend over Salem, Massachusetts—as well as preserve relations with the Swedish community—so he took full control of the proceedings. Because neither woman spoke English, Penn saw to it that a translator was provided. Also, in an attempt to secure the fairest possible sentence, he made sure that every single member of the jury hailed from their neighborhood. Finally, he converted the trial into an investigation, prohibited any lawyers from taking part, and appointed himself as the sole judge.

The official records imply that, when the proceedings began, only one of the so-called witches showed up. Her name was Margaret Mattson, and she pled not guilty. Numerous accusers testified against her, but their claims more or less consisted of hearsay. Afterward, Penn began questioning Mattson. Although the record may have been embellished in the succeeding centuries, one back and forth supposedly included Penn asking, “Art thou a witch?," to which Mattson replied in the negative. “Hast thou ever ridden through the air on a broomstick?” he continued. Mattson didn’t seem to understand this inquiry. “Well,” Penn supposedly said, “I know of no law against it.” A truly bizarre ruling followed. Essentially, the jury found both women guilty of being regarded as witches by their neighbors, but not of actually practicing witchcraft. In 1862, historian George Smith described this as a “very righteous, but rather ridiculous verdict.”

9. HE GOT INTO A BORDER DISPUTE WITH MARYLAND.

Later on in 1684, Penn was compelled to return to England on behalf of his colony. Over half a century earlier, George Calvert, the first Lord Baltimore, was given control of a massive land tract, one that stretched from the 40th parallel to the Potomac River, and from the western source of the river to the Atlantic Ocean. After Calvert’s death in 1632, his descendants organized the new colony, which they dubbed Maryland. Then along came Penn, who unwittingly caused a boundary controversy with the founding of Philadelphia. As he laid the groundwork for the future City of Brotherly Love, he failed to realize that much of it was actually located beneath the 40th parallel. Naturally, this irritated Maryland’s supervising family. In 1682, Penn aggravated them further when he obtained a grant in modern-day Delaware. Charles Calvert—the third Lord Baltimore—disputed his northern neighbor’s right to this area, as well as everything that lay north of the 40th parallel. Seeking a compromise, the two men met up in 1683, but the session failed to bear any fruit, prompting both parties to sail for England, where they sought an audience with the Commission for Trade and Plantations.

Upon hearing each man’s case, the Commission chose to divvy up the Delaware peninsula. Everything south of Cape Henlopen was given to Maryland. Meanwhile, all that lay above the Cape was split vertically, with the eastern half going to William Penn and the western bit handed over to Maryland. (In case you were wondering, modern Delaware voted to break off from Pennsylvania on June 15, 1776. The event gave birth to an annual holiday called Separation Day, which falls on the second Saturday of June.) However, the question of where the Pennsylvania-Maryland border should lie went unresolved. This matter wouldn’t be settled until the 1760s, when surveyors Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon plotted out the most famous dividing line in America.

10. PENN SUPPORTED THE ESTABLISHMENT OF A EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT.

Cumulatively, William Penn spent less than four years of his life in Pennsylvania. After returning to London in 1684, he wouldn’t set foot in the New World again until 1699. During that interim, the Quaker kept himself busy. In 1693, he added a new published work to his bibliography. Titled Essay Towards the Present and Future of Europe by the Establishment of a European Parliament, it was written as a response to the continent’s ongoing, seemingly never-ending wars. Some 300 years before the European Union was founded, Penn called for an international governing body that would consist of 90 voting members to represent all the major (and minor) European countries. But, to his dismay, the essay had no discernable effect on European affairs.

11. LATE IN LIFE, HE WAS ACCUSED OF TREASON.

In politics, the friendships you make can be a blessing one minute and a curse the next. Penn shared a close bond with King James II, a fact that probably helped him secure a favorable outcome in the Pennsylvania/Maryland border spat. But he soon discovered that being associated with James II had its downsides. Unlike his predecessor and most of England’s populace, the monarch was a Catholic. Although this inspired much unrest throughout his reign, James II managed to keep the peace by virtue of his Protestant daughter, Mary. Since it was assumed that she’d take the throne after his death, the King’s opponents grudgingly tolerated him.

An untimely birth changed all that. In 1688, James II was blessed with a son. Assuming this male heir would be raised Catholic, a group of Parliament dissidents reached out to Prince William of Orange, Mary’s husband. That November, William’s forces inadvertently overthrew James II, who panicked at the sight of them and fled to France with his infant son. The following year, William and Mary were crowned King and Queen. Penn would be arrested multiple times in the next few years, including once when James II sent him a letter, but with some help from his friends he managed to get of trouble.

12. HIS SECOND WIFE TOOK CHARGE OF PENNSYLVANIA FOR OVER A DECADE.

Penn wed his first wife, fellow Quaker Gulielma Springett, in 1672. After 32 years of marriage—during which she gave birth to eight children, three of whom reached adulthood—she passed away in 1694. Two years later, Penn again tied the knot, this time with Hannah Callowhill, a bride who, at 26, was less than half his age. While she was pregnant with the couple’s first child, Hannah joined her husband on a transatlantic voyage back to Pennsylvania in 1699. Their stay in the New World was destined to be short-lived; financial woes pulled William back to England in 1701. Although he suggested that she stay behind, Hannah insisted on joining him for the return journey.

Penn’s ability to govern his colony from abroad was compromised by three paralytic strokes he suffered in 1712. As her husband’s health deteriorated, Hannah stepped up. Over the next six years, she oversaw Pennsylvania’s affairs from an ocean away, mailing instructions off to governor Charles Gookin and collaborating extensively with James Logan, Penn’s colonial advisor. Penn died July 30, 1718, but Hannah continued to run Pennsylvania for another eight years after his passing.

13. WILLIAM AND HANNAH PENN BECAME HONORARY U.S. CITIZENS IN 1984.

Penn spent most of his days in England and died over 50 years before the colonies declared their independence. Nevertheless, he is sometimes ranked among America’s founding fathers. He has also received some high praise from legendary statesmen; Thomas Jefferson, for instance, once called him “the greatest law-giver the world has ever produced.” Hannah, too, has a legion of admirers (and deservedly so). On November 28, 1984, they were both posthumously named honorary citizens of the United States. Only six other people have ever received this honor.

14. HE’S LINKED TO A PHILLY SPORTS CURSE.

Philadelphia is world-famous for its rabid sports fans, who were denied any sort of championship for a quarter century. Between the 76ers’ NBA Finals victory in 1983 and the Phillies’ 2008 World Series win, no major professional team from the City of Brotherly Love managed to take home a title. What caused this drought? The standard answer is William Penn—or rather, his statue.

Perched atop Philadelphia’s city hall is a 37-foot, 27-ton bronze likeness of the Quaker visionary. Hoisted into place in 1894, the statue represented the highest point in Philly for more than 90 years. According to legend, a gentlemanly agreement stipulated that no building in town would ever stand taller than the cap on Penn’s head.

Evidently, no one told the architects behind One Liberty Place. Built in 1987, the 945-foot skyscraper absolutely towered over the statue. This is said to have enraged Penn’s ghost and/or the professional sports gods. In any event, all four of the major Philadelphia-based franchises promptly hit a decades-long dry spell. Then, in June 2007, an even taller building was completed: The 975-foot-tall Comcast Center. As a symbol of good faith, a tiny, 5.2-inch Penn figurine was affixed to the very top. One year later, the Philadelphia Phillies became MLB champions. Coincidence? Comcast didn’t think so. They’re currently building an even taller skyscraper, and have promised to move the statue.

15. NO, THE QUAKER OATS GUY WASN’T MODELED AFTER HIM.

Speculate all you like, but the company’s official website swears that its logo—which has been evolving since the 1870s—isn’t based on William Penn. “The ‘Quaker Man’ is not an actual person,” reads the FAQ page. “His image is that of a man dressed in Quaker garb, chosen because the Quaker faith projected the values of honesty, integrity, purity, and strength.”

All images courtesy of Getty Images unless noted otherwise