Chess may seem like a placid pursuit, but it has plenty to do with combat. Of course, the game itself is a virtual portrayal of war complete with castles, knights, and royalty. But during World War II, it also took on new significance for wounded and captured soldiers, who were often faced with long hours of monotony and intellectual starvation.

The Geneva Conventions are best known today for their definitions of war crimes, but in 1929, the third convention helped lay out how to treat prisoners of war. The rules governed not just the physical conditions of POWs but their intellectual and moral needs, requiring freedom of religion, proper medical treatment, and respect based on military rank. The convention also contained a provision on recreation, which stated that "so far as possible belligerents shall encourage intellectual diversions and sports organized by prisoners of war."

War relief organizations took that provision seriously—and for many prisoners of war during World War II, the regulation translated into a rousing game of chess. The intellectual pursuit didn't take much room, could be played over the course of time, and was relatively quiet, making it the perfect pursuit for prisons and hospitals filled with people whose range of motion was limited. Throughout the war, chess was championed by organizations like the International Red Cross, which sent chess sets to prisoners in care packages. Soon, chess tournaments could be found in POW camps around the world.

But POWs weren't the only war casualties who loved chess. In 1945, in response to the influx of wounded veterans at the war's end, the United States Chess Federation partnered with the magazine Chess Review to bring chess to injured vets, too. The resulting organization, Chess for the Wounded, didn't just get chess sets into hospitals—it brought some of the biggest names in chess directly to players. Chess greats (many of them women who had not been drafted into service) headed to players' hospital bedsides to challenge them. Among them were Gisela Gresser, the first American woman chess master and one of the greatest players of all time, and several other U.S. women's champions who volunteered.

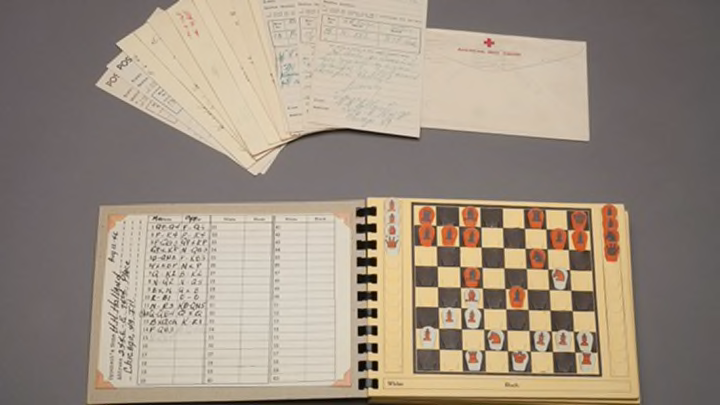

The portable chess board you see above was given to a player by Herbert H. Holland, a U.S. Department of Agriculture worker, attorney, and avid chess player. Holland knew what it was like to be bored and incapacitated in a hospital bed: During World War I, he entered a diabetic coma and spent a total of nearly four years in hospitals recuperating. During those hours, Holland, a self-taught chess player, amused himself by playing chess with his fellow patients—a pastime that eased his boredom and made the long hours more bearable.

Holland never forgot how chess changed his life. During World War II, he collected a total of 1150 chess sets for prisoners of war. He eventually became the head of Chess for the Wounded. Though many players in the program used traditional chess sets, some used postal sets like the one you see above. The cards on the left were used to help players record the moves of several players at once as they mailed their games back and forth to other wounded opponents. Today, it's in the collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame in St. Louis—a testament to the game's little-known connection to the modern horrors of war.