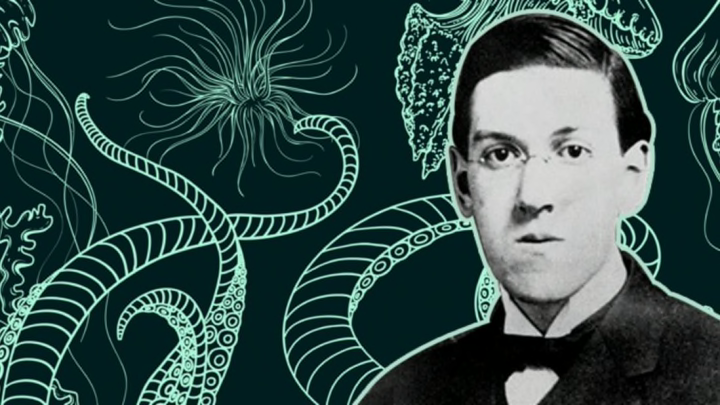

Nearly 80 years after H. P. Lovecraft’s death, his influence over popular culture shows no signs of waning. In his own day, Lovecraft's influences included writers such as fantasist Lord Dunsany, English horror writer Arthur Machen, and his beloved Poe, but Lovecraft’s weird fiction was also shaped by his life events, personal interests, and multiple obsessions. In honor of his 126th birthday, here are just a few.

1. SPACE AND ASTRONOMY

iStock

Contrary to popular perception, Lovecraft was not really a reclusive shut-in as a grown man, enjoying instead a circle of close friends and travel around New England and beyond. During his teenage years, though, he was afflicted with mysterious ailments (which may have been psychological in nature), which often kept him at home and eventually forced him to drop out of school. Being a very precocious autodidact, Lovecraft used this reclusive period to school himself in a number of subjects and developed a keen interest in science, particularly astronomy. At the ripe age of nine, Lovecraft began publishing his own Scientific Gazette. Later, he self-published The Rhode Island Journal of Astronomy and began submitting astronomical articles to local publications. He received his first telescope at age 13, allowing him to indulge his love of stargazing.

Lovecraft’s fascination with the vast cosmos formed the backdrop to the particular brand of weird horror that he created, in which the reaches of space are populated with incomprehensible entities that, like the stars themselves, are foreign and indifferent to the concerns of men. This fascination is seen throughout Lovecraft’s work. In particular, The Color Out of Space, thought by many to be Lovecraft’s most sci-fi piece, features a meteorite with baffling qualities that falls from the sky and horribly alters the farmland on which it lands, as well as the farm’s inhabitants, while The Shadow Out of Time features two extraterrestrial species exploiting Earth for their own ends.

2. THE PAST

Lovecraft’s deep interest in the past formed a counterpoint to his fascination with space and astronomy. As a boy, Lovecraft read voluminously, becoming captivated by ancient Greek myth and history and developing a lifelong affinity for the Baroque era. A dedicated Anglophile (a leaning which was likely influenced by his mother Sarah Susan Phillips Lovecraft’s view of herself as a New England blueblood of English ancestry), Lovecraft was particularly entranced by 18th century England and the Revolutionary War era—though in his case he wished that the British had won. He also adopted 18th century spellings (his characters often offered to “shew” something of interest to one another), and once appeared in a local newspaper wearing a tricorne hat.

It is Lovecraft’s fascination with New England colonial history and Puritanism, though, that is reflected most in his tales, along with his love of colonial architecture. Richard Upton Pickman, the central character of Pickman’s Model (who is described as coming from “old Salem stock”) states of his Boston: “I can shew you houses that have stood two centuries and a half and more; houses that have witnessed what would make a modern house crumble into powder.” Similarly, Keziah Mason of The Dreams in the Witch House is rumored to have been a Salem witch.

3. HIS OWN FAMILY’S PAST

iStock

Lovecraft’s father, Winfield Scott Lovecraft, was confined to a mental institution when he was quite young, forcing young Howard and his mother to live with his grandfather Whipple Van Buren Phillips at the family mansion in Providence. These were happy years for Lovecraft, but financial troubles put the Phillips’ fortunes in increasing jeopardy. Grandfather Whipple’s death in 1904 dealt a final blow, precipitating the sale of the estate and forcing Howard, his mother, and two aunts to move to a more modest home three blocks east of the mansion.

Lovecraft never got over the loss of his family estate, along with the associations of status and happiness tied up with it. He spent a lifetime pining for his family’s former life, and dragged such items as had been salvaged from the estate around with him for life. When he arrived in New York in 1924 to begin an ill-fated marriage to Sonia Greene and an unsuccessful two years of city life, the story goes that he was carting a trunkload of fine linens, china, and books from the Phillips estate, which he eventually crammed into a rundown bachelor pad at 169 Clinton Street in Brooklyn when his marriage began to crumble. Lovecraft’s story Cool Air reflects this reality: Its central character, Dr. Munoz, occupies similarly modest quarters crammed full of gentlemanly trappings. In fact, Lovecraft’s many gentleman scholar characters point to his idealization of upper crust life at the Phillips estate.

4. SEAFOOD

iStock

Lovecraft loved science and he loved history, but there were a litany of strange things he was averse to. Among them: seafood. He was coddled during his years living with his mother and aunts, who allowed him to follow his own sleep schedule and culinary inclinations. This may explain why Lovecraft maintained the palate of a five-year-old throughout his adult life, relishing sweets but rejecting more adult fare. His hatred of seafood was so strong, though, that it seems to defy explanation. On an occasion when a friend tried to take him out for a steamed clam dinner, Lovecraft (who rarely swore) reportedly declared, "While you are eating that God-damned stuff, I'll go across the street for a sandwich; please excuse me."

Whatever the reason for Lovecraft’s extreme disdain for crab cakes, mackerel, and calamari, it proved fertile inspiration for many of his horrifying creations—from the fishy people in The Shadow Over Innsmouth to the now famous octopus-headed god, Cthulhu.

5. RELIGION AND THE OCCULT

Lovecraft’s stories are full of occultists of all stripes, from the Cthulhu worshippers in The Call of Cthulhu to the demonic devotees in The Horror at Red Hook to the authors of the dreaded Necronomicon. While some fans love debating whether Lovecraft was an occultist himself, the fact is, he wasn’t. While confessing to “pagan inclinations” as a child, Lovecraft was a staunch atheist and self-described materialist. It was his skepticism that led to him to collaborate with Harry Houdini, who prided himself on being a debunker of superstition (the publication of Lovecraft and Houdini’s collaboration The Cancer of Superstition was cut short by Houdini’s untimely death in 1926, though the manuscript was recently re-discovered).

Lovecraft was clearly deeply fascinated by the occult, despite his strident disavowal of it, but mainly because it served to deepen the sense of dread in his tales. Despite the color that occult settings provide to Lovecraft’s stories, magic is often revealed to be the product of some form of science that humanity does not understand. His concept of cosmicism rejects the comforts of religion, instead presenting a cold, indifferent cosmos, absent of God.

6. XENOPHOBIA

Lovecraft’s racism has been a difficult issue for many horror and fantasy fans. Xenophobia, of one kind or another, is at the root of many of the strange, alien, and vile beings that populate Lovecraft’s stories. His racism was at its most shrill during his ill-fated New York City years, and this is reflected in the “maze of hybrid squalor,” “dark foreign faces,” and “Persian devil-worshippers” depicted in The Horror at Red Hook, as well as the “yellow, squint-eyed people” swarming over the hellish scape at the end of He. But it is also evident in earlier tales, such as The Facts Concerning the Late Arthur Jermyn and His Family, where the revelation that Jermyn bred with a white ape goddess points to a horror of racial intermixing. Some critics have found racism in other stories, too—like the fish people of The Shadow Over Innsmouth, or more fishy people in The Doom That Came to Sarnath … or maybe he just really, really didn’t like fish?

Toward the end of Lovecraft’s life (he died in 1937 at age 46), he began to soften his views and to grow more accepting of people who were different from himself, but he never transformed into what we might call a progressive today. Many modern fans have found it difficult to square their respect for his genius with their distaste for his problematic views.

7. MADNESS

Artwork by John Holmes for early 1970s Bantam H.P. Lovecraft series. Image credit: Charles Kremenak via Flickr // CC BY 2.0

Characters in Lovecraft’s stories are always teetering on the brink of madness. Whether they begin a story having just escaped a mental institution (like the titular character in The Case of Charles Dexter Ward) or whether they go mad at the end (like the de la Poer scion in The Rats in the Walls), characters are always uncovering forbidden knowledge that will make them lose their marbles.

Lovecraft had his early brushes with madness, including the hospitalization of his father and general instability of his mother. It may be that he feared the same fate for himself, given that he was prone to psychosomatic illnesses and extremely vivid dreams in youth. If so, it certainly would explain his fierce adoption of materialism and atheism. However, Lovecraft also saw the cosmos as one in which man existed side-by-side with knowledge that, if comprehended, would send him over the brink. His most famous story, The Call of Cthulhu, begins with a paragraph that speaks to this worldview:

“The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.”