Cast off the modern world for a moment. Forget the lure of Google and imagine you have never watched a nature program, read an encyclopedia, or learned anything of the natural world outside your small European village. The large animal you are probably most familiar with is a hairy pig, your diet likely revolves around bread and turnips, and your education has been limited to a few passages from the Bible.

Now you're closer to being able to see the world through the eyes of early European explorers, who found animals, plants, foods, and peoples beyond their imagination and recorded their first impressions for us to marvel at today. In her book Penguins, Pineapples and Pangolins: First Encounters with the Exotic, Mental Floss contributor Claire Cock-Starkey collects many of these fascinating meetings. From the “dark politicks” of cuttlefish to the “prodigious bigness” of snakes, here are 10 accounts of the first times explorers encountered new animals, foods, and more.

- Crocodiles have “no passage for excrements.”

- Pineapples are “as big as a man’s head.”

- Cuttlefish have tentacles like “gorgons’ hair.”

- Penguins “taste somewhat fishey.”

- Coffee has “an exquisite taste.”

- Sharks sport “teeth of great length.”

- People ate durian “with great avidity.”

- Snakes grow to “prodigious bigness.”

- Sloths are “very strange to behold.”

- Marijuana makes people “s[i]t sweatinge for the space of 3 hours.”

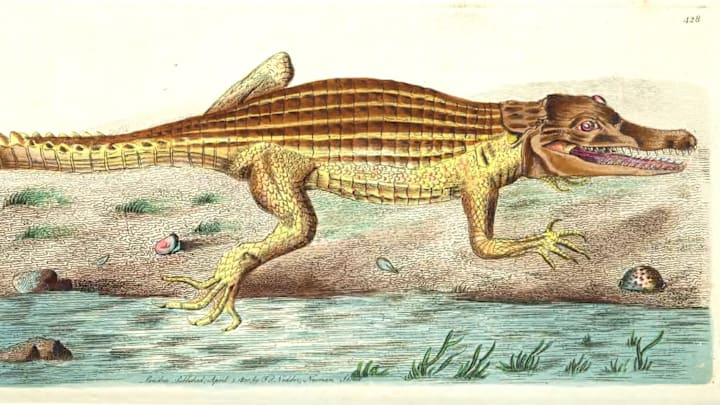

Crocodiles have “no passage for excrements.”

Dr. John Francis Gemelli Careri (1651–1725) was an Italian adventurer who financed his five-year trip round the world by buying and selling goods on his travels. Despite being a well-educated lawyer, his knowledge of natural history was somewhat lacking, as this description of the crocodiles he encountered in the Philippines, taken from his book A Voyage Round the World (1700), attests:

“As for the Crocodils Providence has signaliz’d itself after several manners in them. For in the first place the Females of these Monsters being extraordinary Fruitful, so as to bring sometimes 50 Crocodils, the Rivers and Lakes would have been full of them in a very short time, to the great damage of Mankind, had not Nature caus’d it to lye in wait where the young ones are to pass, and swallow them down one by one; so that only those few escape that take another way.

“Secondly, the Crocodils have no passage for Excrements, but only Vomit the small Matter that remains in their stomachs after Digestion. Thus the Meat continues there a long time, and the Creature is not hungry every Day; which if they were, they could not be fed without the utter Ruin of infinite Men and Beasts. Some of them being open’d there have been found in their Bellies Mens Bones and Skuls, and Stones, which the Indians say they swallow to pave their Stomach.”

In case you were worried, Gemelli Careri’s assumption is incorrect—crocodiles can and do poop.

Pineapples are “as big as a man’s head.”

The appearance and flavor of pineapples certainly made an impression on early explorers, which makes sense given that the most interesting fruit many of them had ever eaten previously was an apple. A New Voyage and Description of the Isthmus of America by Lionel Wafer (1699) was especially effusive about the fruit:

“On the Isthmus grows that delicious Fruit which we call the Pine-Apple, in shape not much unlike an Artichoke, and as big as a Man’s Head. It grows like a Crown on the top of a Stalk about as big as ones Arm, and a Foot and a half high. The Fruit is ordinarily about six Pound weight; and is inclos’d with short prickly Leaves like an Artichoke. They do not strip, but pare off these Leaves to get at the Fruit; which hath no Stone or Kernel in it. ‘Tis very juicy; and some fancy it resemble the Tast of all the most delicious Fruits one can imagine mixd together. It ripens at all times of the Year, and is rais’d from new Plants.”

Cuttlefish have tentacles like “gorgons’ hair.”

Cuttlefish are strange-looking beasts, so it’s perhaps not surprising that John Fryer, in his A New Account of East India and Persia being Nine Years Travels 1672–1681, was so impressed when he first saw one:

“The Crafty Cuttle-Fish its dark Politicks … That is emits a black and cloudy Liquor to disturb the cunning Angler; the Truth whereof I could never observe; only what was more certainly miraculous, its monstrous Figure: The Body was of a duskish Colour, all one Lump with the Head, without scales; it was endowned with large Eyes, and had long shreds like Gorgon’s Hair, hung in the manner of Snakes, bestuck with snail-like Shells reaching over the body; under these appeared a Parrot’s Beak, two Slits between the Neck are made instead of Gills for Respiration … the Inky Matter is bred in the Stomach.”

Penguins “taste somewhat fishey.”

British merchant traveler Peter Mundy, in The Travels of Peter Mundy in Europe and Asia 1608–1667 (1667), was somewhat in awe of the penguins he came across in South Africa. They must have seemed unlike any bird he had seen before, although they were not so exceptional as to prevent him from eating them:

“Penguins is a kinde of Fowle that cannot flye att all, haveing resemblance of Wyngs which hang downe like sleeves, with which, as with Finns, hee swimmeth exceeding swifte. They live on Fish. Hee breedeth on the land, makeing his Neste in holes under low bushes and shrubss. They are easily taken, not being able to flye nor runne, only bite a little to noe purpose, bodied like a Ducke but much bigger, head and bill, like a Gull, walkinge and goeinge almost upright, blacke on the Back, white under the belly, which cometh to their head round over their Eyes with a stroake that Thwarts over their breaste … They taste somewhat fishey. I am also somewhat the learger on this Fowle, because theis are much spoken of, and seemeing verie strange to mee.”

Coffee has “an exquisite taste.”

Coffee originated in Ethiopia and was a relatively modern discovery. Its use as a beverage was first mentioned in the 15th century. The stimulating effects of coffee ensured its popularity, and it was initially drunk by Sufi monks in Yemen to stay awake for nighttime prayer. By the early 15th century, coffee had spread to Mecca, a major meeting place in the Muslim world, allowing the bean to disperse across the Middle East. Italian explorer Pietro Della Valle gives a thorough description of Turkish coffee in Travels in Persia (1658):

“The Turks have a Drink of a black Colour, which during the summer is very cooling, whereas in the Winter it mightily heats and warms the Body … This Drink, as I remember is made with the grain or Fruit of a certain Tree, which grows in Arabia towards Mecca, and the fruit it produces is called Cahue, whence this drink derives its Name, ‘tis of an oval shape, of the same bigness as a middle-sized Olive ...

“The way to make the Drink thereof, is thus: They burn the skin or Kernel of this fruit as it best pleases their fancy or palate, and they beat it to a powder very fine, of a blackish colour, which is not very pleasant to the eye-sight … When they would drink thereof they boyl it in Water in certain pots made on purpose … Afterwards they pour out this Liquor to be drunk as hot as the Mouth and Throat can endure it, not suffering themselves to swallow it but by little and little and at several times, because of its actual heat; and after it has taken the taste and colour of this powder, whereof the thick sinks down and remains at the bottom of the Pot, to make use of it more deliciously, they mingle with this powder of Cahue, much Sugar, Cinnamon and Cloves well beaten, which gives it an exquisite taste and makes it much more nourishing.”

Sharks sport “teeth of great length.”

Dutch adventurer Christopher Fryke recounted his unfortunate experience with sharks in A Relation of Two Several Voyages made into the East Indies (1700):

“These sharks we as often call Men-Eaters in Dutch, because they are very greedy of men’s flesh. They have a large Mouth, which they open very wide, and Teeth of great length, and exceeding sharp, which shut into one another; so that whatever they get between them, they bite clear through. They are about 20 or 24 Foot in length; and they keep about the Ships in hopes of Prey; but are much more frequent in the Indies, than in the Way; where they do abundance of Mischief among the Seamen when they go to swim, as we afterwards found, when we came in the Road near Batavia where one swimming at a distance from the Ship, a Shark came up to him, and drew him under the water, and we never could hear of him more, or so much as see any remnant of him; which made all the old Seamen wonder, who said, They never knew a Shark take any more of a Man, than a Leg, or, it may be, a good Part of the Thigh with it: But for this Man, we did not perceive so much as the Water bloody.

“Near Japara we had a Man, who had lost a Limb by this means, under our hands to cure; and he lived seven Days after it; but at the end of that time he died, being mightily tortured with a vehement Cramp. Another time, at the Isle of Onrust, about eight Leagues from Batavia [Jakarta, Java, Indonesia], our Ship being layed up to mend something of the side of it, the Carpenter going to do something to it, about a Knee deep under Water, had his Arm and Shoulder snap’d off. I took him and bound him up, but to no purpose; for in less than three Hours time, he was dead.”

People ate durian “with great avidity.”

Not all exotic fruits are as alluring as the pineapple, as anyone who has encountered the durian fruit will attest. Although European travelers have known of the durian for over 600 years, its rather unusual odor and flavor has meant it never really caught on in Europe or the United States. A Historical Account of all the Voyages Round the World performed by English Navigators (1773) sums up its unique flavor quite perfectly:

“The durion takes it name from the word dure, which, in the language of the country, means ‘prickle’; and this name is well adapted to the fruit, the shell of which is covered with sharp points shaped like a sugar-loaf: its contents are nuts, not much smaller than chesnuts, which are surrounded with a kind of juice resembling cream; and of this the inhabitants eat with great avidity: the smell of the fruit is more like that of onions, than any other European vegetable, and its taste is like that of onions, sugar, and cream intermixed.”

Snakes grow to “prodigious bigness.”

When observing exotic animals for the first time, some explorers came up with rather imaginative explanations for their behavior. Gemelli Careri’s A Voyage Round the World contains this description of a gigantic snake encountered in the Philippines (most likely the reticulated python, which can grow to up to 32 feet long), and a marvelous theory on how the snake catches its prey:

“There are snakes of prodigious Bigness. One sort of them call’d Ibitin, which are very long, hang themselves by the Tail down from the Body of a Tree, expecting Deer, wild Boars, or Men to pass by, to draw them to them with their Breath, and swallow them whole; and then winds it self round a Tree to digest them. Some Spaniards told me, The only Defence against them was to break the Air between the Man and the Serpent; and this seems rational, for by that means, those Magnetick or attracting Particles spread in that distance are dispers’d.”

Sloths are “very strange to behold.”

Sloths were noted by 16th century Spanish explorers of South America. Summarie and Generall Historie of the Indies (1555) by Gonzalo Ferdinandez De Oviedo contains the following account of a “strange beast,” which, based on his wonderfully evocative description, seems likely to have been a sloth:

“There is another strange beast, which by a name of contrary effect, the Spaniards call Cag-nuolo leggiero, that is The Light Dogge, whereas it is one of the slowest beasts in the World, and so heavie and dull in moving, that it can scarsly go fiftie paces in a whole day: these beasts are in the firme land, and are very strange to behold for the disproportion that they have to all other beasts: they are about two spans in length when they are grown to full bigness, but when they are very young, they are somewhat more grosse then long, they have four subtill feet, and in every one foure claws like unto Birds, and joynd together, yet are neither their claws nor their feet are able to susteine their bodies from the ground, by reason whereof, and by the heaviness of their bodies, they draw their bellies on the ground … they have very round faces much like unto Owles, and have a marke of their own haire after the manner of a Circle … they have small eyes and round & nostrils like a Monkeyes … their chiefe desire is to cleave and stick fast unto trees.”

Marijuana makes people “s[i]t sweatinge for the space of 3 hours.”

English merchant sailor Thomas Bowery (1669–1713) encountered cannabis in Bengal, India. Bowery and 10 of his English friends sampled some, becoming the first Europeans to record getting high:

“It soon took its Operation Upon most of us, but merrily, Save upon two of our Number, who I Suppose feared it might doe them harme not being accustomed thereto. One of them Sat himselfe downe Upon the floore, and wept bitterly all the Afternoone; the Other terrified with feare did runne his head into a great Mortavan Jarre, and continued in the Posture 4 hours or more, 4 or 5 of the number lay upon the Carpets (that were Spread in the roome) highly Complimentinge each Other in high termes, each man fancyinge himselfe noe less than an Emperour. One was quarralsome and fought with one of the wooden Pillars of the Porch, untill he had left himselfe little Skin upon the knuckles of his fingers. My Selfe and one more Sat sweatinge for the Space of 3 hours in Exceedinge Measure.”

Read More Stories About Animals:

A version of this story was published in 2016; it has been updated for 2024.