The experience of living through a war can seem almost unimaginable for those who haven't been through it, but the diaries kept by real people can help bring it to life. Many important diaries kept by political leaders and ordinary folks during World War II have been digitized or preserved, and while reading a few of them might require a trip to the library, they're valuable reminders of what life was like during those tumultuous times.

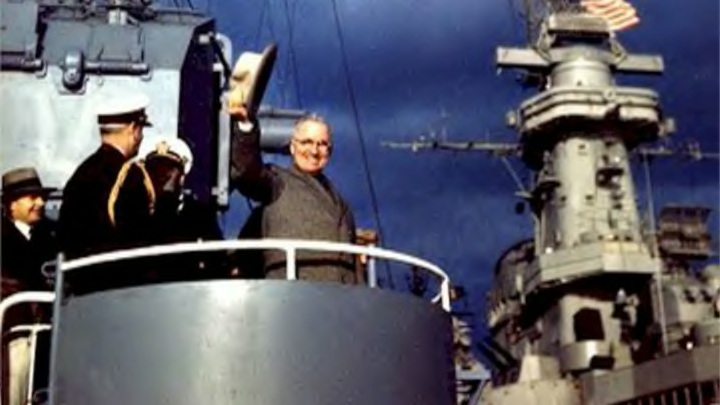

1. HARRY S. TRUMAN, 33RD PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES

Harry S. Truman became president close to the end of World War II, in April 1945, after Franklin D. Roosevelt died suddenly. He kept a diary during this crucial period, and large portions have been released to the public for free via the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library in Independence, Missouri. Truman’s diaries reveal some of the difficult decisions he had to make, including the one to drop an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan. On July 25, 1945, Truman wrote:

“This weapon is to be used against Japan between now and August 10th. I have told the Sec. of War, Mr. Stimson, to use it so that military objectives and soldiers and sailors are the target and not women and children. Even if the Japs are savages, ruthless, merciless and fanatic, we as the leader of the world for the common welfare cannot drop that terrible bomb on the old capital or the new. “He and I are in accord. The target will be a purely military one and we will issue a warning statement asking the Japs to surrender and save lives. I’m sure they will not do that, but we will have given them the chance. It is certainly a good thing for the world that Hitler’s crowd or Stalin’s did not discover this atomic bomb. It seems to be the most terrible thing ever discovered, but it can be made the most useful …”

The full text of Truman’s 1947 diary has been digitized and transcribed, allowing us to read his own words from his own hand.

2. THE WORLD’S MOST FAMOUS DIARIST, ANNE FRANK

Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

Such was the impact of her diaries, detailing her experiences in Nazi-occupied Amsterdam, that Anne Frank has become one of the most famous diarists in the world. Anne started her diary aged just 13 and wrote it over two years while she and her family hid from the Nazis in a secret annex of an old warehouse. Anne describes how Jews in Amsterdam were treated, writing on October 9, 1942:

“Our many Jewish friends and acquaintances are being taken away in droves. The Gestapo is treating them very roughly and transporting them in cattle cars to Westerbork, the big camp in Drenthe to which they're sending all the Jews … If it's that bad in Holland, what must it be like in those faraway and uncivilized places where the Germans are sending them? We assume that most of them are being murdered. The English radio says they're being gassed."

was so affecting in part because she remained so positive despite the terrible world in which she was living. One such example of her inspiring attitude was written on July 15, 1944:

“It’s difficult in times like these: ideals, dreams and cherished hopes rise within us, only to be crushed by grim reality. It’s a wonder I haven’t abandoned all my ideals, they seem so absurd and impractical. Yet I cling to them because I still believe, in spite of everything, that people are truly good at heart.”

Tragically, Anne and her family were caught by the Nazis in 1944 and Anne was sent to Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp, where she died of typhus at the age of 15. Her diary was first published, by her father Otto, in 1947, and there have been many editions since.

3. JOSEPH GOEBBELS, HITLER’S MINISTER FOR PROPAGANDA

Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

was Hitler’s minister for enlightenment and propaganda from 1933 to 1945 and was instrumental in spreading Nazi doctrines. He kept a diary starting in 1923, and the early years mainly cover Goebbels' failed love affairs. But after 1925, Goebbels became fixated on Hitler and his diary reflects this. He wrote in November 1925:

“Hitler is there. Great joy. He greets me like an old friend. And looks after me. How I love him! What a fellow! Then he speaks. How small I am. He gives me his photograph. With a greeting to the Rhineland. Heil Hitler! I want Hitler to be my friend. His photograph is on my desk.”

Once Goebbels rose to become a senior Nazi, his diary entries often concerned Nazi policy, such as the extermination of the Jews. In February 1942 he wrote:

“The Jewish question is again giving us a headache; this time, however, not because we have gone too far, but because we are not going far enough.”

By 1941 Goebbels' extensive diaries filled 20 volumes and he began to realize what a valuable historical resource they would be. From then on, he dictated them to a stenographer and had them kept in an underground vault at Reichsbank, Berlin. In 1945 glass plates featuring microfilmed copies of the diaries were buried at Potsdam, where they were later found by the Russians and shipped to Moscow, where they lay until 1992. Twenty-nine volumes of the diaries were subsequently published in Germany between 1993 and 2008, but so far only some of the diaries from the war years have been published in English.

4. HAYASHI ICHIZO, JAPANESE KAMIKAZE PILOT

Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

Kamikaze translates as “divine wind” and was the Japanese practice during World War II of sending young men in planes loaded with explosives on suicide missions. The vast majority of kamikaze pilots were under the age of 25, conscripted into the army sometimes against their will. One such young man was Hayashi Ichizo, a student who was drafted into the army in 1943 aged just 23. While stationed at a Japanese Naval Base from January to March 1945, Ichizo recorded his thoughts in his diary. In one entry, he admitted he was not entirely convinced of his mission:

“To be honest, I cannot say that the wish to die for the emperor is genuine, coming from my heart. However, it is decided for me that I die for the emperor.”

In another heart-breaking entry, Ichizo yearns to be back with his mother, as a small child:

“I dread death so much. And yet, it is already decided for us … Mother, I still want to be loved and spoiled by you. I want to be held in your arms and sleep.”

More extracts from kamikaze pilots' diaries can be found in Kamikaze, Cherry Blossoms and Nationalisms by Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney.

5. VICTOR KLEMPERER, LIVING IN DRESDEN AS AN "UN-GERMAN" GERMAN

Eva Kemlein, via Wikimedia Commons // CC-BY-SA 3.0

Victor

Klemperer was of Jewish descent and yet a baptized Christian, a complicated situation that made him "un-German" according to the Nazis. Klemperer began keeping a diary in 1897, aged 16, and his diaries span German history from Kaiser Wilhelm II through the Weimar Republic and the rise of the Nazis, ending in communist East Germany. However, Klemperer’s diaries from 1933–45 have gained the most attention. As Hitler was elected on March 30, 1933, he wrote:

“Hitler Chancellor. What, up to election Sunday on March 5, I called terror, was a mild prelude. Now the business of 1918 is being exactly repeated, only under a different sign, under the swastika. Again it's astounding how easily everything collapses.”

Klemperer was a Professor of Romance Languages at the Technical University of Dresden, but under the Nazis he was forced to give up his position and was even banned from entering the university library. Furthermore, he and his wife were forced to leave their home and move into a mixed house for Jewish people (as his wife was non-Jewish), he had his typewriter confiscated, was forced to wear a yellow star, and even had to surrender his cat. Klemperer’s diaries were published in full in Germany in 1995 to great critical acclaim and have since been translated into English.

6. U.S. ARMY GENERAL GEORGE S. PATTON

Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

George S. Patton was a U.S. Army general who was the field commander in North Africa and kept a diary throughout the war years. Despite being a highly successful commander, he was thought of as politically unskilled and made a grievous error in 1944, when newspapers reported that Patton had said it was the destiny of Britain and America to rule the world, leaving out America’s Soviet Union allies (the Army quickly responded by saying that he had been misquoted). As a result, Patton was called before President Eisenhower (Ike) and wrote of the encounter in his diary entry from May 1, 1944:

“Ike said he had recommended that, if I were to be relieved and sent home, I be not reduced to a Colonel, as the relief would be sufficient punishment, and that he felt that situations might well arise where it would be necessary to put me in command of an army. “I told Ike that I was perfectly willing to fall out on a permanent promotion so as not to hold others back. Ike said General Marshall had told him that my crime had destroyed all chance of my permanent promotion, as the opposition said even if I was the best tactician and strategist in the army, my demonstrated lack of judgment made me unfit to command.”

Despite the dressing down, Patton was given the critical role as commander of the FUSAG, or First US Army Group, for the Invasion of Normandy. An almost entirely fictitious army, they were intended to make the Germans think that an invasion was going to land at Pas-de-Calais instead of Normandy. Patton died in 1945 after sustaining injuries in a car crash, and his diaries were used to write the memoir War as I Knew It, which was published in 1947.

7. IVAN MAISKY—SOVIET AMBASSADOR TO LONDON 1932–43

Getty Images

Ivan Maisky served as the Russian Ambassador to London from 1932 to 1943 and during that time kept a fantastically detailed diary. The diary was kept hidden in the Russian Foreign Ministry until 1993, when historian Gabriel Gorodetsky found it and realized he had stumbled upon a fantastic historical prize revealing a Soviet insider’s thoughts in the lead-up to the war. Maisky was a central player in London society and had connections with top people from Winston Churchill to Lord Beaverbrook. In one diary entry from September 4, 1938, he revealed what happened when he visited Winston Churchill at his country estate:

“Then the three of us had tea – Churchill, his wife and I. On the table, apart from the tea, lay a whole battery of diverse alcoholic drinks. Why, could Churchill ever do without them? He drank a whisky-soda and offered me a Russian vodka from before the war. He has somehow managed to preserve this rarity. I expressed my sincere astonishment, but Churchill interrupted me: “That’s far from being all! In my cellar I have a bottle of wine from 1793! Not bad, eh? I’m keeping it for a very special, truly exceptional occasion.” “Which exactly, may I ask you?” Churchill grinned cunningly, paused, then suddenly declared: “We’ll drink this bottle together when Great Britain and Russia beat Hitler’s Germany!” I was almost dumbstruck. Churchill’s hatred of Berlin really has gone beyond all limits!”

The full diaries are published by Yale University Press as The Maisky Diaries: Red Ambassador to the Court of St James’s, 1932-1943, edited by Gabriel Gorodetsky.

8. "VINEGAR JOE"—GENERAL JOSEPH STILWELL

Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

Nicknamed "Vinegar Joe" for his caustic personality, General Joseph Stilwell was a general in the U.S. army who commanded troops in Burma under Chinese leader Chiang Kai-Shek (whom he nicknamed "the peanut") during World War II. Stilwell complained openly, in his signature staccato fashion, about his difficulties dealing with the Chinese nationalist leadership, writing on April 19, 1943:

“Worked all P.M. 5:00 to see Peanut. A hell of a session. More demands … sneers and complaints. “Counter-offensive”!! More stupidity. Acts scared. “Morale at low ebb”. Is he crazy? Close to it.”

Stilwell’s diaries reveal his experiences escaping from Burma in 1943, as the Japanese closed in, and later his thoughts on commanding troops in Japan. The Joseph Stilwell diaries are kept at the Hoover Institute and are fully available online.

9. MARIE VASSILITCHKOV AND A PLOT TO ASSASSINATE HITLER

Marie Vassilitchkov was a White Russian princess who escaped Russia with her family after the Russian Revolution before moving to Berlin in 1940, where she worked in the German Foreign Ministry from 1940–44. There Vassilitchkov worked under Adam von Trott zu Solz, a leading anti-Nazi who was part of the 20 July Plot to assassinate Hitler. Vassilitchkov kept a diary during this period, covering the assassination plot (which she was aware of but not directly involved in) and the subsequent bombing of Berlin. On November 22, 1943 she wrote about the destruction of Berlin’s Lutzowplatz:

“All the buildings had been destroyed, only their outside walls still stood. Many cars were weaving their way cautiously through the ruins, blowing their horns wildly. A woman seized my arm and yelled that one of the walls was tottering and we both started to run.”

Vassilitchkov later escaped to Vienna and finally settled in London. Her diaries were published in 1988, ten years after her death.

10. FIELD MARSHAL LORD ALANBROOKE

Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

Field Marshal Lord Alanbrooke (or just plain Alan Brooke to his friends) was a British military strategist who helped to plan the Normandy invasions in 1944 and was central to the British war effort. Alanbrooke frequently disagreed with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and yet because of his military insight remained a key part of Britain’s military strategy. Alanbroke’s diaries were first published in 1957, but were heavily edited and redacted for both national security and to soften his criticisms of powerful figures like Churchill. Alanbrooke wrote in his diary about how his American equivalent, George Marshall, viewed Churchill:

“I remember being amused at Marshall’s reactions to Winston’s late hours, he was evidently not used to being kept out of his bed till the small hours of the morning and not enjoying it much! He certainly had a much easier time of it working with Roosevelt, he informed me that he frequently did not see him for a month or six weeks. I was fortunate if I did not see Winston for 6 hours.”

A new un-censored version of Alanbrooke’s diaries were published in 2001, finally revealing the real tensions and truths behind his relationship with Churchill.

11. CHESTER HANSEN, U.S. SOLDIER AND AIDE TO GENERAL OMAR N. BRADLEY

Diaries kept by World War II soldiers are very rare, because keeping a diary was generally forbidden due to the danger of it falling into enemy hands. This did not stop Chester Hansen, an aide to General Omar N. Bradley, who was instrumental in the North African campaign and commanded troops during the D-Day Landings. Trained as a journalist, Hansen kept meticulous records of his war years, completing some 300,000 words in his diary. On June 6, 1944, while headed toward the coast of Normandy, France, Hansen wrote that:

Like others in the Army party, Bradley was up at 3:30. He is on the bridge, a familiar figure in his ODs with Moberly infantry boots and OD shirt, combat jacket, steel helmet. He smiles lightly as though it is good to be nearer the coast of France and get the invasion under way.

Hansen also recorded much of the intense warfare he took part in. This extract [PDF] from April 1, 1943 relates to a battle fought in the Tunisian desert:

Ten minutes later 9 JU88’s came over, disappeared and returned out of the sun [sic]. We ran for the trenches—generals rather casually. I last remember looking up to see ships. Terrible concussion hit me—tore back my helmet—dropped to slit trench thinking I had been hit in neck. No blood, greatly relieved. Shrapnel breaking overhead, riddled my rifle. Got out, helped wounded.

Although Hansen often wrote of battles, he also revealed some of the more amusing details of life during World War II, recounting that Dwight D. Eisenhower sent Bradley an ice-maker because the latter was fed up with getting served warm whiskey. The diaries have yet to be digitized but the archive along with letters, maps, newspaper clippings and other ephemera are kept at the Army Heritage and Education Center in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

12. NELLA LAST—A BRITISH WOMAN’S EXPERIENCES OF LIFE IN WARTIME BRITAIN

, which spanned 1939–66, was kept for the British Mass Observation archive in order to preserve the thoughts of ordinary people during wartime and beyond. Last was a housewife who lived in Barrow-in-Furness in Lancashire and was 49 years old when she started her journal. She carefully records how life changed as the war progresses, as well as her thoughts on the conflict. On March 13, 1940, she wrote of her feelings on hearing Finland had surrendered to the invading Russians:

“All the brave struggles of Finland – such futile bravery now seems to hang over me like a black fog that shuts out the sun. It's easy enough when things go right, to talk and think of 'God's plan' but so hard to reconcile any plan with the martyrdom of the Finns and the Poles. Kill kill kill, sorrow and grief and loneliness, senseless cruelty and hatred, drowning men, mud, cold and a baffling sense of futility – what a Hell broth.”

In 1941 the Germans began bombing Britain, and Last was forced to endure many bombing raids. She wrote of one terrible night on May 4, 1941:

“A night of terror. Land mines, incendiaries and explosives were dropped and we cowered thankfully under our indoor shelter. I really thought our end had come. Now I've a sick shadow over me as I look at my loved little house. Ceilings down, walls cracked, doors off.”

Nella continued to write her diary after the war and right up until 1966. The diaries of her war years were published in 1981.