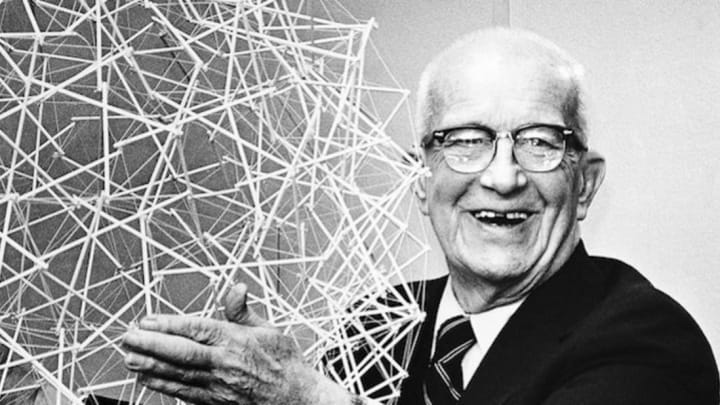

Inventor, polymath, eccentric (definitely), genius (maybe): Buckminster (“Bucky”) Fuller (1895-1983) was, at the very least, a man with a hurricane of a mind, always dreaming up new ideas and new designs, trying earnestly to create a better world through technology. Many of his inventions were ultimately flops, though his greatest passion—the geodesic dome—can now be found around the world. In honor of his birthday, July 12, 1895, here are 15 facts you may not have known about the man behind the dome.

1. HE SAW THINGS UNUSUALLY FROM A YOUNG AGE.

Literally. Fuller suffered from poor vision; as a child, before receiving his first pair of glasses, he refused to believe that the world was not blurry. And—metaphorically at least—he would continue to see things a bit differently throughout the rest of his life, conjuring up new uses for familiar objects and championing designs that ranged from the surreal to the bizarre. He disliked the label “inventor,” preferring to call himself a “comprehensive, anticipatory design scientist,” or “comprehensivist” for short.

2. HE WAS A LOUSY STUDENT.

His university studies did not go well. Halfway through his freshman year at Harvard, he used the money that had been set aside for his tuition to entertain some chorus girls in New York. He was given the boot. In fact, he never received a university degree—but then, neither did Nicola Tesla or Thomas Edison. (The Harvard professors might be relieved not to have had to read Fuller’s writing; his collected works would eventually fill more than 2000 pages—most of it rambling and barely structured.)

3. HE SERVED—AND INVENTED.

Fuller was in the U.S. Navy from 1917 to 1919, where he invented a winch for rescue boats that could pluck downed airplanes from the water in time to save the lives of pilots. A pilot was saved in this manner at a naval training center in Virginia, as Fuller anxiously looked on; he later described it as one of the happiest moments of his life. This invention would save hundreds of pilots’ lives.

4. AN EARLY TEST DRIVE OF HIS FAMOUS CAR TURNED DEADLY.

His eye-catching car, the Dymaxion (the name was pulled out of thin air by an associate as a "word portrait" of his work) was a teardrop-shaped marvel (see the video above, which appears to show 1930s film footage). It had three wheels—two at the front and one at the rear—and one steered by controlling the rear wheel. It could turn on a dime. Within three months of the car’s debut, one of the vehicles crashed, killing the driver and injuring a passenger. Investors pulled out, and only three prototypes were ever built.

5. IT'S STILL DANGEROUS.

When automotive journalist Dan Neil took a faithful replica of the Dymaxion for a test drive on a track near Nashville last year, it did not go well; Neil says he feared for his life. In spite of never exceeding 40 mph, “several times I was seized with terror when the 20-foot vehicle developed uneasy, oscillating swivels, with the tail wanting to wobble like a shopping cart’s bad wheel,” he wrote of the experience.

6. MANY OF HIS IDEAS WERE FLOPS.

Genius or not, many of Fuller’s ideas were duds. Among them: the Dymaxion House, a hexagonal-shaped, single-family home that was to be mass-produced from metal and could hang from a central mast; when a family moved, the whole house could move too. Similarly, the Dymaxion Bathroom—a single unit equipped with a bathtub, toilet, and sink—never caught on; only 13 were ever built. He also envisioned a city shaped like an eight-sided tetrahedron that could house a million people. He imagined it floating in Tokyo Bay. None of these ideas would come to fruition.

7. HIS WORLD MAP FOLDS BUT IT DOESN'T DISTORT (MUCH).

POVRay via Wikimedia Commons // CC BY-SA 3.0

Mapping the spherical Earth onto two-dimensional paper is tricky. Some distortion is unavoidable; think of how the Mercator projection inaccurately portrays Greenland as the size of Africa, when in reality it is a fraction of the size. In the 1950s, after years of work, Fuller developed a scheme in which the Earth’s surface is projected onto an icosahedron—a polyhedron consisting of 20 triangles of equal size. The distortion on each triangle is minimal, and the whole affair can be laid flat such that no continents are split. The scheme also emphasizes the “connectedness” of the world’s land masses.

8. HE INVENTED HIS OWN GEOMETRY.

In mid-career, Fuller decided to invent his own geometry, which he called Synergetic Geometry. He used 60-degree angles—like those you’d see in the triangles that make up his beloved domes—as the basic unit of measure. (It never caught on.) In a similar vein, he liked to invent words, making up neologisms as needed. Among his coinages: “livingry” (as opposed to weaponry, which he referred to as "killingry"). He also popularized the term “spaceship Earth.”

9. HE PREDICTED A LIFE AQUATIC.

Fuller imagined that one day we would live in massive ocean settlements; he also imagined massive, balloon-like floating communities which, heated by the Sun’s rays, would float up into the clouds. (And this was decades before George Lucas gave us the “cloud city” of The Empire Strikes Back.)

10. HIS FIRST DOMES—BOTH LARGE AND SMALL—DIDN'T FARE WELL.

Paula Bustamante/AFP/Getty Images

His first attempt to build one of his now-famous geodesic domes, using the slats from Venetian blinds, fell in on itself as soon as it was completed. (Some of those watching felt is should be called a “flopahedron.”) The first commercial use of Fuller’s dome design came in 1953, when the Ford Motor Company built one at their headquarters in Dearborn, Michigan (modifying a design that had been used at the World’s Fair in Chicago in 1934). The structure was 93 feet across yet weighed only 8.5 tons. It was destroyed by a fire in 1962.

11. NOW THE DOME IS FOUND AROUND THE GLOBE.

His famous geodesic dome design has now been reproduced more than 300,000 times worldwide, and can be seen everywhere from NORAD’s defensive radar installations to Epcot at Walt Disney World. (Called Spaceship Earth, Epcot’s defining structure is actually two geodesic domes that were put together to create a sphere.) Part of the dome’s appeal is that it can enclose the largest possible volume of space with the least amount of material. So if you need a structure that’s big, cheap, and quick, the geodesic dome may be for you.

12. HE BELIEVED THAT HUMANS DIDN'T ORIGINATE ON EARTH …

In spite of his passion for science and engineering, Fuller never accepted the theory of evolution. “We arrived from elsewhere in Universe as complete human beings,” he once wrote. (Fuller never used “the” in front of “Universe,” which he always capitalized.)

13. … AND LED MENSA FOR NEARLY A DECADE.

He served as the second World President of Mensa (the high-IQ society) from 1974 to 1983. Though he died long before the Internet became common, he witnessed the beginning of the computer age and envisioned an era when computers and technology could be used to solve the world’s problems. “You may . . . want to ask me how we are going to resolve the ever-accelerating dangerous impasse of world-opposed politicians and ideological dogmas,” he once noted. “I answer, it will be resolved by the computer.”

14. THE "BUCKYBALL" IS NAMED AFTER HIM.

In 1985—just two years after Fuller’s death—chemists managed to create a form of carbon whose shape reminded them of a scaled-down version of the famous engineer’s domes. The molecule—shaped like a sphere and consisting of 60 carbon atoms—was named Buckminsterfullerene, or buckyball for short. (Even shorter, and less poetically, you can call it C-60.)

15. HIS UNCONVENTIONAL THINKING CONTINUES TO HAVE INFLUENCE TODAY.

The Fuller challenge (administered by the Buckminster Fuller Institute) spotlights outside-the-box design efforts; recent winning projects include the use of agricultural waste to manufacture packaging materials and building insulation, living breakwaters that protect vulnerable coastlines, and a method for reversing desertification of grasslands and savannas, thus mitigating the effects of climate change.