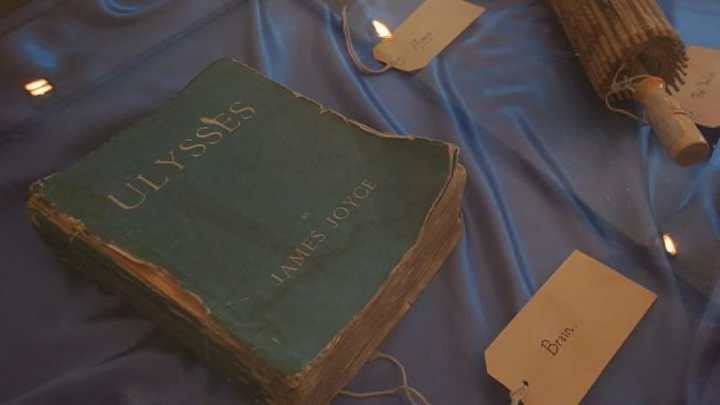

Perhaps no book has triggered such strong and polarizing reactions as James Joyce’s Ulysses. The gargantuan novel’s 265,000 words have simultaneously enchanted, bewildered, and downright revolted readers and critics since the Irish novelist first published them about a century ago. Having endured despite being banned in the U.S. and U.K. for years on moral grounds, Ulysses is today hailed as a masterpiece of the modernist movement, frequently ranking atop the various lists of the English language’s greatest works—as well as the most difficult. The epic follows the travails and encounters of one Leopold Bloom through an ordinary day in Dublin, June 16, 1904. The date is now commemorated annually by fans the world over as Bloomsday.

Joyce once commented that he had placed within Ulysses "so many enigmas and puzzles that it will keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant," which they invariably have. So much so, in fact, it has become known as “the novel to end all novels” for the scope, complexity, and sheer volume of its pages. Reading it is a feat of endurance: It is made up of 18 “Episodes” each adopting a separate form and reading completely differently. Chock-full of symbolism, experimentation, obscure references and historical allusions, the author’s wit and mastery of language reward the most patient of students as forcefully as they can daunt the faint of heart.

Veterans and the uninitiated alike can appreciate the liveliness and vivid imagery of the vocabulary on display in Joyce’s prose. Illuminate your otherwise-ordinary Bloomsday observances by citing from among Joyce’s apt yet archaic trove of word choices.

1. DOFF

To remove an item of clothing (as in the opposite of “to don”) or raise one’s hat as a sign of respect. While this term may have fallen out of fashion with the waning of formal hattery, it is no less useful a verb today than it was on the streets of Dublin at the turn of the 20th century.

2. GALOOT

Mildly derogatory slang approximated as “oaf” or “lummox.” It can be applied light-heartedly to someone who appears awkward or lacking in wits. In one of the internal monologues Ulysses has come to be synonymous with, the central character Bloom eyes suspiciously an unwelcome stranger, questioning the appearance of a “lankylooking galoot.”

3. STOLEWISE

Catholic terminology features heavily in Ulysses. A stole is a piece of priestly vestment. The fabric is draped over the back of the shoulders, or stolewise, leaving long loose ends hanging down the front on either side. Joyce’s use of the adverb gives a devout allusion to an otherwise mundane scene.

4. BEHOOF

A noun referring to one’s profit or advantage, related to the verb behoove. Joyce drew liberally among words with vastly different origins, the distinctive sound produced when pronouncing behoof being due to its Anglo-Saxon roots.

5. CHIVY

In a dialogue concerning Shakespeare, Joyce mentions a swan “chivying her cygnets toward the rushes.” The verb, implying repetitive goading to action, was employed by Joyce to, alongside other equally archaic words and phrases, create a sense of Elizabethan England.

6. HERESIARCH

The founder or major propagator of a heresy. The classically-read character Stephen Dedalus muses about the fate of an ”illstarred heresiarch” in Ulysses’s opening Part. In this section, known as “The Telemachiad,” we are first graced with the fleet-tongued poet’s stream of consciousness. Another of Joyce’s ecclesiastic terms, the label can be applied nowadays to the proponent of an idea counter to established beliefs.

7. EGLANTINE

Another name for Rosa eglanteria, a rose with prickly stems also known as sweetbriar. The term ultimately derives from Latin aculentus, or prickly. Joyce masterfully employed the term with double meaning: at face value a metaphor for a messy situation, while likewise eponymously describing the actions of a character, one John Eglinton.

8. FELLAHEEN

Arabic in origin, this plural noun refers to peasants of the Levant. “The masters of the Mediterranean are fellaheen today,” Professor MacHugh effectively summarizes. Fellaheen was injected into public consciousness in Joyce’s time by German historian Oswald Spengler, bringing with it connotations of a people disinterested in the cultural or political vyings happening beyond their control. Joyce’s rendering adds a fine, epic point on the more general expression “here today, gone tomorrow.”

9. ANTIPHONE

In choir or chanting, the antiphone is a response one side of the chorus makes to end an alternating sequence. But Joyce unexpectedly turns the word into a verb, when Buck Mulligan “antiphoned” a witty comment onto another’s statement with dead-pan emphasis. The word may be rarer today, but chiming in on others’ ideas has endured.

10. OSTLER

Syncopated from the French hosteler, a person employed at an inn, hostelry, or stable. The word appears in Ulysses as a stand-in for the humble working class.

11. LOLLARD

Another reference to Christian theology, Lollardy was a form of doctrinal skepticism in medieval England, presaging some beliefs and criticisms of the Protestant Reformation which followed. From a medieval Dutch word lollaerd, meaning “mumbler,” this term can be used pejoratively to refer to quiet dissenters.

12. CAUBEEN

A beret or flat cap once popular among the Irish lower classes (ostlers included), now a part of military dress. A loanword from the Irish language, it literally means “old hat” and could thus be applied to any headpiece. Just don’t forget to doff your caubeens on Bloomsday in salute to fellow logophiles.