There were a lot of details that Lin-Manuel Miranda couldn’t fit into the Broadway musical Hamilton—that time Hamilton claimed to have communicated with a dead Revolutionary War commander as a joke, for example, or his epic rivalry with New York Governor George Clinton, or a mic-dropping diss rap directed at John Adams.

He also couldn’t fit in much about Peggy, the Schuyler sister who, in the show, is worried about being out too late downtown and disappears after the first act. (The actress who plays her becomes Maria Reynolds in the second act.) But in real life, this Schuyler sister was much beloved by Hamilton—and much more than “and Peggy.” Here are a few things you should know about her.

1. Peggy Schuyler’s name wasn’t actually Peggy.

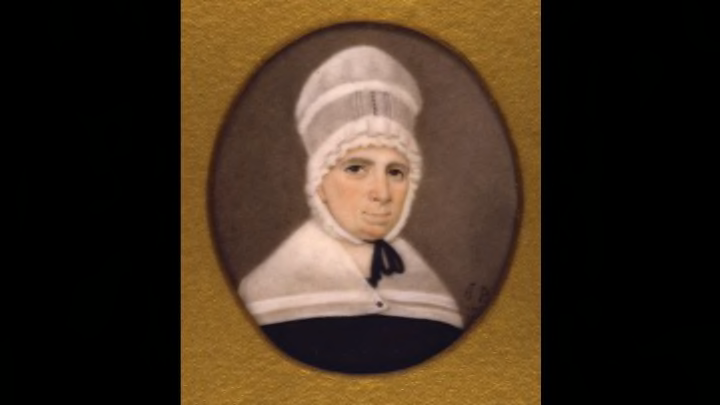

Peggy was a nickname; depending on the source, she was either Margaret or Margarita Schuyler. She was born in Albany in September 1758.

2. Peggy Schuyler had “a kind of wicked wit.”

The Schuyler family was one of the wealthiest in New York, and each daughter was, according to Hamilton biographer Ron Chernow, “smart, beautiful, gregarious, and rich … they collectively charmed and delighted all the visitors to the Schuyler mansion in Albany.”

Philip and Catherine Schuyler had eight children who survived to adulthood, including three sons; Peggy, the third of Schuyler’s daughters, was “very pretty,” according to the Scottish poet Anne Grant, and possessed “a kind of wicked wit.” The elder Catherine Schuyler’s biographer, Mary Gay Humphreys, described Peggy as having “animated and striking” features; as a young woman, she was “lively” and “the favorite of dinner-tables and balls” and, in later in life, was “bright, high-spirited [and] generous.”

But not all descriptions were so rosy. In a 1782 letter to Hamilton, statesman James McHenry compared Peggy to her sister Angelica (who he calls “Mrs. Carter” because her husband, John Barker Church, was forced to take the alias John Carter during the revolution), noting that “Peggy, though, perhaps a finer woman, is not generally thought so. Her own sex are apprehensive that she considers them, poor things, as [Jonathan] Swifts [sic] Vanessa did; and they in return do not scruple to be displeased. In short, Peggy, to be admired as she ought, has only to please the men less and the ladies more.” According to Hamilton biographer Ron Chernow, Peggy was “sarcastic” and “very beautiful but vain and supercilious.”

3. Peggy Schuyler first became acquainted with Alexander Hamilton via letter.

In 1780, shortly after Hamilton began courting Eliza (or, as Hamilton also called her, Betsey), Washington’s aide-de-camp wrote to Peggy at length of his love for her sister; he included a bit of flattery for good measure:

“I venture to tell you in confidence, that by some odd contrivance or other, your sister has found out the secret of interesting me in every thing that concerns her; and though I have not the happiness of a personal acquaintance with you, I have had the good fortune to see several very pretty pictures of your person and mind which have inspired me with a more than common partiality for both. Among others your sister carries a beautiful copy constantly about her elegantly drawn by herself, of which she has two or three times favoured me with a sight. You will no doubt admit it as a full proof of my frankness and good opinion of you, that I with so little ceremony introduce myself to your acquaintance and at the first step make you my confident.”

Between when their courtship began and when he married Eliza in December 1780, Hamilton became close to all the Schuylers.

4. Alexander Hamilton wrote a piece in which he hoped Peggy Schuyler would serve as the main character.

In October 1780, Hamilton wrote to Eliza, asking her to tell Peggy that he’d soon open a letter he had from her. “I am composing a piece, of which, from the opinion I have of her qualifications, I shall endeavour to prevail upon her to act the principal character,” he wrote. “The title is ‘The way to get him, for the benefit of all single ladies who desire to be married.’ You will ask her if she has any objections to taking part in the piece and tell her that if I am not much mistaken in her, I am sure she will have none.” (He added to his soon-to-be wife, “For your own part, your business is now to study the way to keep him, which is said to be much the most difficult task of the two, though in your case I thoroughly believe it will be an easy one and that to succeed effectually you will only have to wish it sincerely.”)

5. Peggy Schuyler once faced off against some Tories.

In 1781, Albany was not much safer than the warfront: Local Native American tribes and British loyalists had been running raids all over the area. Philip Schuyler, who was the mastermind of a spy ring, was even the subject of a British kidnapping plot; on August 7, according to Chernow, a group of Tories and Native Americans surrounded the Schuyler mansion and forced their way into the home searching for the patriarch. The family—including Angelica and Eliza, both pregnant—fled upstairs during the assault, realizing too late that they’d left behind Catherine Schuyler’s baby daughter (also named Catherine). When Peggy snuck downstairs to retrieve the infant, who was in a cradle near the door, one of the raiders stepped in front of her with a musket and demanded to know where General Schuyler was. According to Chernow, Peggy replied, coolly, that he had “Gone to alarm the town.” The raiders, afraid that troops were coming, fled—and Peggy grabbed baby Catherine and ran back up the stairs. According to legend, one raider threw a tomahawk at her but missed, hitting the bannister, which still has a mark.

6. Peggy Schuyler married well.

In June 1783, when she was almost 25, Peggy married a distant cousin, Stephen Van Rensselaer III, 19; it was likely an elopement. (In fact, Eliza was the only Schuyler sister who didn’t elope.) Stephen was a descendent of Kiliaen Van Rensselaer, an Amsterdam merchant who was the first patroon—a person granted land and privileges by the Dutch government of New York—of a huge tract of land that included Albany county. This made Stephen a patroon as well, and he had plenty of money and servants. After her marriage, Peggy earned another nickname, this one bestowed upon her by Hamilton: “Mrs. Patroon.” By 1789, the couple had three children, only one of whom would survive to adulthood.

7. Peggy Schuyler died young.

By 1801, Peggy had been ill for two years. Hamilton, who had resigned as Treasury Secretary six years before, was in Albany on business that March when Peggy took a turn for the worse. He frequently wrote to Eliza, at home in New York City, about her sister’s health. “Your Sister Peggy has gradually grown worse & is now in a situation that her dissolution in the opinion of the Doctor is not likely to be long delayed,” he wrote on February 25. The situation was dire enough, he said, that Peggy’s husband had requested that their only surviving son, then 11, be brought home.

But by March 9, things were slightly better. “Your Sister Peggy had a better night last night than for three weeks past and is much easier this morning,” Hamilton told Eliza. “Yet her situation is such as only to authorise a glimmering of hope.” On March 10 he wrote again, telling her that he would return home but for “the situation of your Sister Peggy, her request that I would stay a few days longer and the like request of your father and mother … There has been little alteration either way in Peggys [sic] situation for these past four days.”

It wouldn’t be long before things got much worse. On March 16, Hamilton wrote to Eliza with the sad news that her sister, not yet 43, had passed away: “On Saturday, My Dear Eliza, your sister took leave of her sufferings and friends, I trust, to find repose and happiness in a better country. … Viewing all that she had endured for so long a time, I could not but feel a relief in the termination of the scene. She was sensible to the last and resigned to the important change.” He planned to stay for the funeral and leave for New York City the day after. “I long to come to console and comfort you my darling Betsey,” he wrote. “Adieu my sweet angel. Remember the duty of Christian Resignation. Ever Yrs, A H.”