As a high school senior in St. Paul, Minnesota, Charles Schulz knew he wanted to be a cartoonist. He also knew he didn’t want to go to college or pursue any formal art education, afraid of being told he couldn’t cut it. Instead, Schulz asked his father for $169 to enroll in Art Instruction Schools, a Minneapolis-based correspondence course that promised students they could become proficient in any number of artistic pursuits by taking a 12-step lesson via the mail.

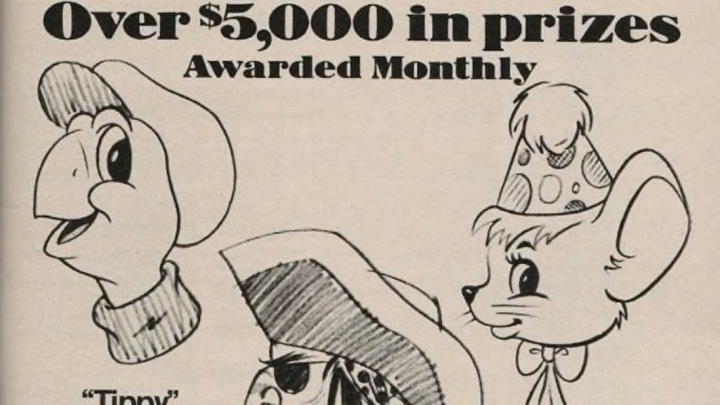

Since the 1920s, they’d been running ads in newspapers and magazines like this one:

While Tippy the Turtle was probably the most recognizable figure, it’s not known which character Schulz drew and submitted. It could have been Winky the Deer, or Reggie the Raccoon, or Spunky the Donkey. It also really didn’t matter if he could do it well; applicants to the school were accepted so long as their check cleared.

Despite the exorbitant cost to his father during the Great Depression, Schulz enrolled. Thanks to the debut of his Peanuts strip in 1950, he remains their most famous alumnus.

Founded in 1914 to find talent for a local engraving business, Art Instruction Schools (AIS) was one of a number of mail-away art courses that prospered in the middle of the 20th century. With photography yet to fully take hold in advertising, commercial illustration was still a popular field. Universities, however, didn’t have the kind of extensive art curriculums of today. Thanks to eye-catching advertisements in newspapers, magazines, and on matchbooks, tens of thousands of would-be artists signed up for the programs.

AIS’s biggest competitor for that business was Famous Artists School, which counted Norman Rockwell among its celebrity endorsees—although he rarely evaluated submissions. At its peak in the 1950s and 1960s, Famous Artists had 40,000 doodlers taking the course. Once a drawing “test” was mailed in, the company would sometimes dispatch door-to-door salesmen to convince budding talent they had what it took to pursue a formal education in the arts and boasted accreditation by the Distance Education and Training Council.

Both AIS and FAS are still in operation today, although it’s difficult to estimate how many of their pupils have gone on to have careers in illustration; some of their critics have pointed out that art is very much a hands-on learning experience. Schulz, however, was enamored enough with AIS to migrate to their Minneapolis headquarters after a stint in the Army, becoming an instructor in the late 1940s. While there, he struck up several friendships with fellow teachers and asked if he could use their names for a strip he was planning to submit to newspaper syndicates. Both Linus Maurer and Charlie Brown said yes.