In the middle of London, right between St. Paul’s Cathedral and the Museum of London, is a small public space known as Postman’s Park. Though the park itself is small—less than an acre—it commemorates some immensely heroic deeds.

Its story began in 1887, when painter and sculptor George Frederic Watts wrote to The Times to suggest a unique piece of art to commemorate Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, stating:

“Among other ways of commemorating this fiftieth year of Her Majesty’s reign, it would surely be of national interest to collect a complete record of the stories of heroism in everyday life. The character of a nation as a people of great deeds is one, it appears to me, that should never be lost sight of. It must surely be a matter of regret when names worthy to be remembered and stories stimulating and instructive are allowed to be forgotten.”

As an example, Watts cited the story of Alice Ayres, a 25-year-old woman who tried to save her three young nieces from a house fire by pushing a featherbed from a window to cushion the fall. By the time it was her turn to jump, she was dizzy from inhaling smoke, and was unable to jump far enough out to clear the shop sign below the window. She hit the sign as she fell, then missed the featherbed and hit the pavement. She died from her injuries several days later. Two of her nieces survived.

Unfortunately, Watts’s idea was nixed. But it caught the attention of Henry Gamble, the vicar of St. Botolph’s Aldersgate church. Gamble was trying to raise funds to purchase a plot of land that neighbored St. Botolph’s, and thought Watts’s memorial would help arouse public interest in the project. The pairing worked and construction began.

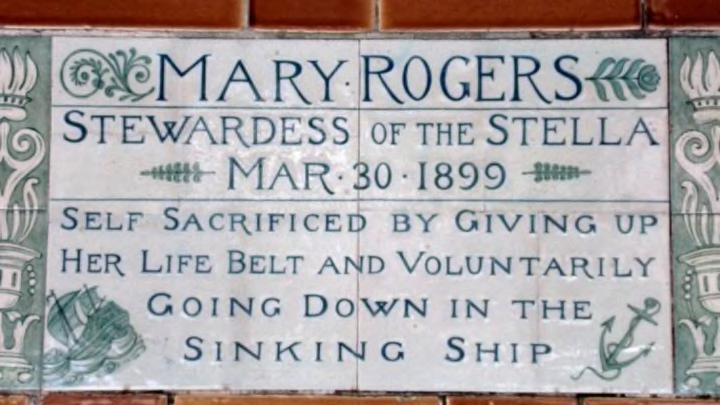

Iridescent, Wikimedia Commons // CC BY-SA 3.0

Unfortunately, by the time the Watts Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice opened in 1900, Watts himself was too ill to attend and see the four inaugural tablets. When he died in 1904, his wife, Mary, made sure that he, too, was remembered for creating the tribute.

Despite his death, Watts continued to influence the memorial for decades. He had collected a number of newspaper clippings of stories he found worthy of memorializing; Mary and a committee from St. Botolph's chose many of the remaining honorees from his clipping catalog.

The 54 tablets include quite a few heroes who saved people from drowning or fire, but there are also cases that are quite unique, such as that of Samuel Rabbeth.

Rabbeth was tending to a four-year-old diphtheria patient named Leon Jennings, who had just received a tracheotomy to help with breathing problems. Unfortunately, young Leon developed more problems after the surgery when mucus became lodged in the breathing tube and threatened to suffocate him. Aware of the high risk of infection, Rabbeth put his lips to the tube and sucked the mucus out himself. He contracted the disease and died of it later that month—followed, a few days later, by Leon.

The latest addition was installed in 2009 to honor Leigh Pitt, a printworker who saved a nine-year-old boy from drowning, but then disappeared under the water himself. Pitt's addition was the first new tile in 78 years—and it would appear that it's also the last. In 2010, "representatives from all the significant interest groups reached a conclusion that it was no longer appropriate to add further tablets to the memorial."