Shortly after Memphis city judge Beverly Boushe handed down a $26 fine to the 235-pound man with a streak of white hair running down the middle of his grimacing head, Boushe told reporters that it was the first time he could ever recall seeing a white defendant being represented by a “negro attorney.”

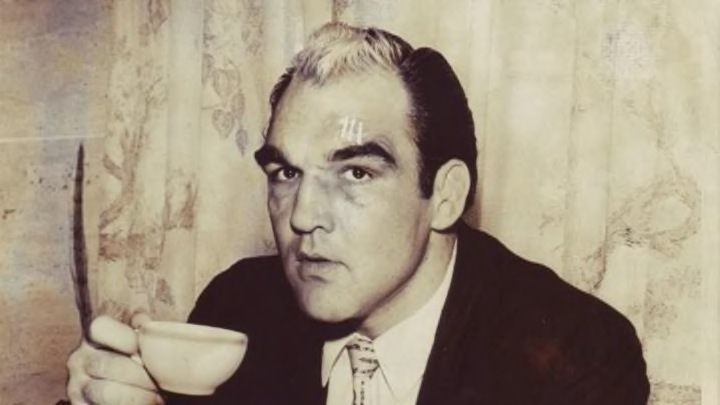

The white man in front of his bench was Roscoe Monroe Merrick, better known by his stage name of “Sputnik” Monroe. His lawyer, Russell Sugarmon, Jr., faced Boushe and tried to argue that the police allegations over Monroe’s disorderly conduct were unfounded. All he had done was visit a black cafe to hand out tickets to one of his professional wrestling events, a right afforded to him according to the abolition of the Jim Crow laws.

Boushe didn’t respond to the argument and levied the fine. It was January 1960. Monroe would repeat this process several times, always accused of a vague infraction known as “mopery” by drinking alongside black patrons. Each time, he’d pay the penalty.

In a segregated Memphis, Monroe was looking to make news and fill seats at Ellis Auditorium. The difference between “Sputnik” and other pro wrestlers of the era was that he welcomed—and eventually insisted—that his black fans sit wherever they chose.

In living out his ring persona on racially divisive streets, Monroe was about to single-handedly desegregate public venues. While wearing only his underpants.

Monroe was born in Dodge City, Kansas on December 18, 1928 to a single mother. His father had died in a plane crash one month before his birth. When Monroe was four, his mother remarried, this time to a baker named Virgil Brumbaugh. That decision would have lasting effects on Monroe’s sense of equality. His stepfather’s bakery had black employees; his nanny was a woman of color. Monroe had never been given a reason to feel different or superior to the people who populated his life.

When he was 17, Monroe entered the Navy and navigated his way through post-war assignments in Japan before leaving and deciding to pick up impromptu grappling matches at carnivals. At six-feet, two-inches and well over 200 pounds, Monroe was solidly built and had developed a taste for wrestling while in high school. He adopted the name “Pretty Boy Roque” and began traveling to wrestling territories in the South just as the sport was introducing more colorful and bombastic performers with increasingly exaggerated violence. He didn’t mind cutting himself with a razor to put on a bloody show for fans; he insisted his streak of white hair came after he was blasted with a wooden—not steel—chair, a giant splinter having lodged in his head.

Monroe had an aptitude for angering audiences, particularly when he would introduce the notion of racial equality into his appearances. In 1957, while driving to Alabama for a show, he grew so tired that he pulled over at a gas station and invited a young black hitchhiker to take the wheel. When he arrived at the arena, he slipped his arm around the man in a sign of solidarity. When the white audience jeered, Monroe leaned over and kissed him on the cheek.

The crowd almost frothed at the mouth. One woman who had exhausted all of the typical invective called him “Sputnik,” the Russian satellite that had recently gone up. It was supposed to be an insult. The name stuck.

As a self-described grappler made of “twisted steel and sex appeal,” word traveled to Memphis, then a hotbed for wrestling, that Monroe could draw a crowd—one that largely hated him, but a paying crowd nonetheless.

In 1958, promoters invited him to town. Almost immediately, he began frequenting Beale Street, a stretch of road that was home to many black businesses. Monroe would dress outlandishly, laugh and drink with minorities, and pass out tickets to his matches. He repeated his visits every night for six months straight. On the date of the events, thousands of supporters would be lined up outside the arena door.

But Ellis Auditorium, like virtually all public venues in the South, segregated their seats. Black attendees would be placed in a tiny “crow’s nest,” a balcony in the nosebleed section, even if the white-only seats on the floor were half-empty.

Monroe thought turning away paying customers was senseless both morally and financially and told the promoter as much. To prove his point, he started bribing the arena employee in charge of counting entrants to allow more black ticket holders inside. So many spilled in that the building had no choice but to let them sit wherever they wanted.

When he was confronted about the tactic, Monroe became more belligerent. He could draw crowds of up to 15,000, making him the biggest star in Memphis wrestling—and by default, their most profitable performer.

“There used to be a couple of thousand blacks outside wanting in,” Monroe once told the Washington Times. “So I would tell management I’d be cutting out if they don’t let my black friends in. I had the power because I’m selling out the place, the first guy that ever did, and they sure wanted the revenue.”

Green was the only color that mattered. Ellis Auditorium quickly became the first public gathering in Memphis to be desegregated.

Natalie Bell via WKNO

According to wrestlers who knew him, Monroe never took a break from his gimmick of being an agitator. His wife and child dyed their hair to match his famous streak—so did local high school kids, whose yearbook photos would display evidence of their devotion to him. Once, walking into a Dillard’s department store with a black friend, he told the man not to remove his hat, which was typically done as a sign of servitude. “Don't take that damn hat off,” he said. “We may have a fight, but we ain't taking our hat off.”

Visiting a county fair one Sunday afternoon, he strolled up to some cowboys and suggested they get their shoes shined by two black children working nearby. When they ignored him, Monroe kept pressing until one of the men knocked him unconscious. After claiming in the press that he was kicked by a bull, requiring stitches, Monroe invited the man for a rematch in the ring. He declined.

Monroe kissed black babies, draped his arm around black friends, and generally behaved like he was completely oblivious to the racial divide. White crowds booed him; black crowds loved him. Memphis became a capital of wrestling, with Monroe befriending the likes of Sam Phillips—Elvis Presley’s producer at Sun Records—and recording a song.

The more tensions eased in the 1960s, however, the less disruptive Monroe appeared. As business dwindled, he began taking his act back on the road. A divorce, excessive drinking, and odd jobs kept him from enjoying the same success he had earlier.

In the 1970s, Monroe had an idea. He returned to Memphis, this time with a tag-team partner named Norvell Austin. Austin was in his early 20s and happened to be black. When the two took the advantage over their opponents, Monroe would dump black paint over them and scream, “Black is beautiful!”

In an area still struggling to evolve from its biases, it was enough to put him back on the map. Monroe wound up wrestling into his 60s before settling down and getting steady work at a gas station: He died in 2006 at the age of 77.

Once, when he was lacing up his boots to get ready for an appearance in Louisville at the height of his fame, a woman approached him and thanked him for helping her to get out of the crow’s nest balcony at Ellis Auditorium. Monroe, she said, had really changed things for the better.

Without many people around, the man who had picked fights with cowboys, cut himself with razor blades, and insisted he wasn’t a “do-gooder” teared up a little. Then he went back to being the bad guy.