Thomas Jefferson’s influence on American culture extends far beyond the Declaration of Independence. He was also one of early America’s most prominent and passionate boosters of wine, influenced by his sojourns in France as the American ambassador. And now you can explore which wines captured his fancy in the 18th and early 19th centuries, from 1791 to 1803.

The New York Public Library has digitized one of Jefferson’s account books held in the library’s archives, as The Wall Street Journal reports, noting the type and quantity of wines he purchased in addition to his travel records and other expenditures.

He spent $22.50 in duties for importing 200 bottles of Champagne, according to this note.

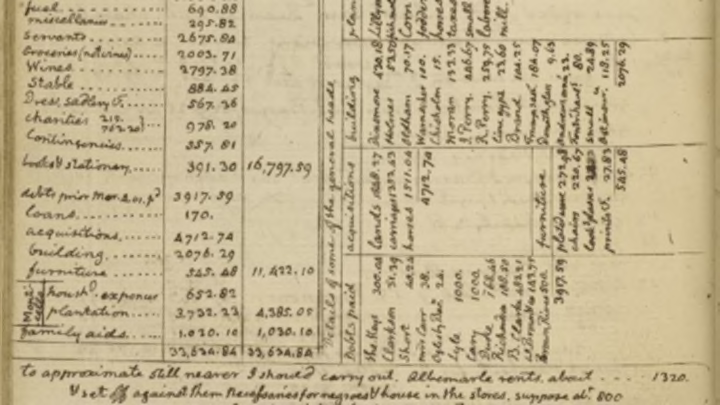

It’s a little difficult to decode Jefferson’s minute scribbles, but if you spend enough time with the book you can begin to sketch out his life just before and during his first years in the White House (he took office in 1801). In 1791, for instance, he records the sum of his quarterly household expenses, which included about $271 in furniture and $35 in groceries. He details elsewhere how much he spends in hiring coaches, when he gives people money out of charity (about $979 in his first year as president), and whose debts he's repaid.

As for his drink purchases, as Wall Street Journal wine writer Lettie Teague, who flipped through the book in person in the library’s archives, details:

There was an order for 100 bottles of Champagne ($172.50) and many orders for ‘pipes’ of Madeira—a pipe equals about 125 gallons of wine—as well as ‘Sauterne’ and Sherry and Claret, aka Bordeaux, as well as ‘Burgundy of Chambertin’ and ‘white Hermitage.’ There was even an entry for Montepulciano, a humble Italian red wine that I was surprised to see was served at the White House. Jefferson even detailed some wine shipping costs.

In his first year as president, from March 1801 to March 1802, Jefferson writes that he spends $2797.38 in wine, compared to $2003.71 in groceries. (He spent nearly $11,000 on wine during his tenure as president.)

When he retired from politics, Jefferson threw himself into winemaking, procuring cuttings to grow native American wine grapes (then largely sour and terrible, to Jefferson’s frustration) at Monticello. However, he would remain a better wine drinker than wine maker.

“Though he planted vines of every description—natives and vinifera both—at Monticello over a period of half a century (the earliest record in his garden book is in 1771, the last in 1822), there is no evidence that Jefferson ever succeeded in producing wine from them, and probably after a certain time he ceased even to hope very strongly in the possibility for himself," scholar Thomas Pinney writes in his book A History of Wine in America. "But he cared much that others should succeed, and, by virtue of his zeal and his eminence, can be called the greatest patron of wine and winegrowing that this country has yet had." In this, he definitely put his money where his mouth was.

[h/t The Wall Street Journal]