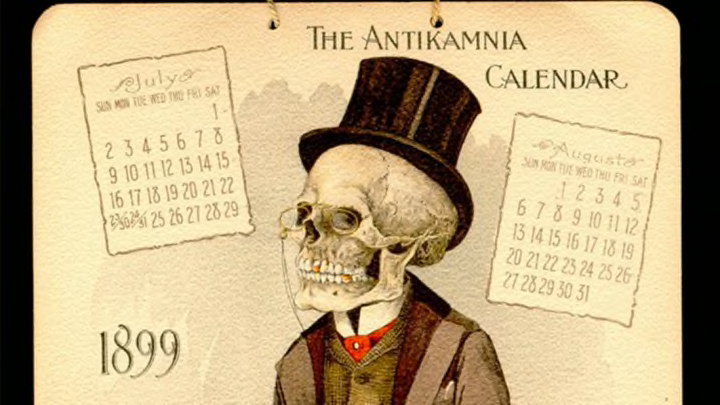

These days, we’re used to pharmaceutical advertising featuring pastel shades, dulcet tones, and 10 paragraphs of fine print. But at the end of the 1800s, one St. Louis company marketed their signature pain-relieving product with a series of macabre calendars featuring skeletons at work and play. Ironically, the very product they were advertising would later be shown to be fatal.

Although the name of the company—and the images—seem vaguely European, the Antikamnia Chemical Company was a home-grown affair. The company was founded by two former drug store owners in St. Louis in the late 1880s to sell Antikamnia, a medicine designed to combat both pain and fever (the name comes from Greek words meaning “opposed to pain”). Although the formula of Antikamnia varied over time, its principal ingredient was always acetanilide, a coal tar derivative. The company touted its little white pills as a “certain remedy, unattended by any danger,” useful for everything from flu to headaches, and especially handy taken as a preventative before sports or even shopping.

Wellcome Images // Public Domain

The company aggressively marketed its goods to physicians with direct mailings and promotional products. (Although the medicine was never patented and required no prescription, its makers hoped the freebies would entice doctors to recommend the products.) One of those promotional goods was a limited-edition calendar created for the years 1897 to 1901, and featuring the darkly comic illustrations of one Louis Crusius. A doctor as well as an artist, Crusius’s illustrations once graced the windows of the drug store he co-owned in St. Louis. In 1893, he’d published The Funny Bone, a compilation of his jokes and drawings. His calendars, though, seem to have been his most successful effort, and they still routinely fetch hundreds of dollars on eBay, at antique stores, and on ephemera-related sites. Sadly, Crusius wouldn’t survive the run of his calendars—he died in 1898, at age 35, of renal cell carcinoma.

And as it turned out, the calendars themselves were promoting a dangerous product. Acetanilide, the coal-tar derivative, had the unfortunate side effect of producing cyanosis, meaning it turned extremities blue from a lack of oxygen. Deaths related to the ingredient were reported as early as 1891. One 1907 article in the California State Journal of Medicine article entitled “Poisoning by Antikamnia” described a woman who had taken the drug as being “practically without pulse, cyanosed, with shallow breathing, and a ‘leaky skin.'”

Fortunately, Antikamnia was an early target of the progressive campaigners at the FDA, which ruled in 1907 that products containing acetanilide had to be clearly labeled as such. However, the company attempted to skirt the rules by changing its product in the U.S. market to contain acetaphenetidin, an acetanilid derivative, and then advertising that its product was acetanilide-free. That worked for a little while, but as the journal Confluence explains, in 1910 U.S. marshals seized a shipment for violating the Pure Food and Drug Act, and the case that followed went all the way to the Supreme Court.

The Court eventually ruled that Antikamnia was in violation of the Act for not stating that the drug contained an acetanilid derivative, a ruling that was considered a landmark in support of Progressive Era reform. The Antikamnia Chemical Company’s fortunes tanked not long afterward, although not before making founder of the company Frank A. Ruf rich. At his death in 1923, his estate was worth more than $2 million.

While the calendars survive as a charming memento of a time when pharmaceutical advertising could be a little less saccharine, it’s hard not to wonder what the victims of Antikamnia might have made of these frolicking skeletons if they had only known what was really being advertised.

But despite its dangers, Antikamnia does seem to have been effective at dampening pain. About 50 years later, scientists discovered that the primary metabolic product of acetanlilide is paracetamol, now known as acetaminophen—or Tylenol.

All images via BibliOdyssey // Public Domain unless otherwise specified.