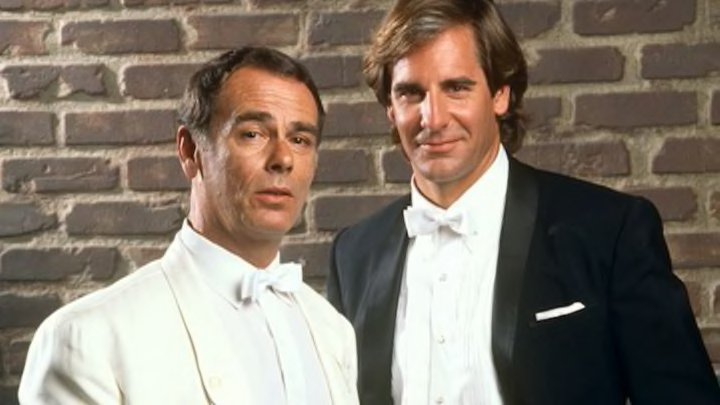

For five seasons between 1989 and 1993, physicist Dr. Sam Beckett “leaped” from person to person to right epic wrongs and change the course of world history in Quantum Leap. Scott Bakula starred as Beckett, and in each episode he ended up inside a different person, ranging from a pregnant woman to Lee Harvey Oswald. Beckett’s snarky hologram sidekick, Al (Dean Stockwell), helped the doctor navigate the historical sequences. The show highlighted social issues and occasionally aired divisive episodes.

Magnum P.I. and NCIS creator Donald P. Bellisario pitched the show because he wanted to do an anthology with two characters and felt the time travel element would be attractive to legendary NBC president Brandon Tartikoff. (It was.) There were rules to Beckett’s time travel, though: He was born in 1953 and wasn’t allowed to travel outside of his age—though one episode did see him leaping into his great-grandfather’s body to experience the American Civil War. Also, Beckett could only see the person he possessed when he looked in a mirror, and it was up to him to figure out the problem that needed to be fixed.

Though it wasn’t a ratings juggernaut, for two summers in a row NBC aired episodes five nights a week to get more people watching. As a result, the show gained a cult status, and fans—who called themselves Leapers—held conventions throughout the years and even funded Stockwell’s star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame Star. In 1993, the show met its demise when NBC abruptly canceled it. Here are some facts about the series, on the 30th anniversary of its debut.

1. The show's title came from a physics books.

Show creator Donald P. Bellisario explained the provenance of the show’s title to Emmy TV Legends. “I was reading a book called Coming of Age in the Milky Way and it took man from when he looked up at stars and all the way to quantum physics, and it gave the history of everything. And the quantum leap is a physical thing that happens that you can’t explain. That was it. I never explained who was leaping Sam—was it God, fate?"

2. Dean Stockwell's film career helped land him his role on Quantum Leap.

Dean Stockwell had toiled in movies and television for years, but his star was burning brightly after he appeared in David Lynch's Blue Velvet in 1986 and received an Oscar nomination for 1988’s Married to the Mob. “I had done television for years, but nobody was interested in me,” Stockwell told Emmy magazine. “After the films, things changed. I had been told I had no TV-Q, and now it didn’t matter. Quantum Leap came along. From the moment I read it, I thought it was perfect, that it was going to be a success.”

Once cast, Stockwell hoped the show would last a while. “My idea going into Quantum Leap was to get stranded in it for five or six years. Why not? I have done something like 60 films. I don’t have anything to prove in that area, and I don’t care to prove anything in theater.” The show ended up giving Stockwell four years of solid work.

3. Scott Bakula nailed his audition.

Bellisario’s casting director had Scott Bakula come in and read for the part of Dr. Sam Beckett. After Bakula read, Bellisario contained his excitement and calmly thanked Bakula for his great reading. “He walked out and the door closed. And I went, ‘That’s the guy,’” Bellisario told Emmy TV Legends. “I didn’t want to say it in front of him. Then they came to me and said, ‘How about Dean Stockwell?’ He just did Married to the Mob, his feature career is rejuvenated. They said, ‘He’d like to do it,’ and I said, ‘In a minute,’ and that was it. It was the only two people I had to cast.”

4. The chimp episode was a hit with animal rights activists.

In “The Wrong Stuff—January 24, 1961,” Beckett leaps into the body of a chimp that is trapped in a research lab and headed to space. The writer of the episode, Paul Brown, met with primate expert Jane Goodall. “She was so moved by the idea, she’s been sending him articles about the inhumane treatment of lab animals to help in his research,” Quantum Leap co-executive producer Deborah Pratt (and voice of Ziggy) told TV Guide. “I’ve asked Paul to show the necessity of using animals for medical research—as well as showing that inhumane treatment is wrong. We like to lay out both sides and let the audience decide what to think.”

5. Quantum teleportation may be a real thing.

The phrase quantum leap entered the dictionary in 1956 and is defined as “an abrupt transition of a system described by quantum mechanics from one of its discrete states to another, as the fall of an electron in an atom to an orbit of lower energy,” or “an abrupt change, sudden increase, or dramatic advance.”

In 2014, the University of Geneva teleported a photon “to a crystal-encased photon more than 25 kilometers (15.5 miles) away.” There’s a lot of scientific jargon in the article, but basically this means that maybe, someday, more than just particles will be transported through optical fibers.

6. One episode featured a young Donald Trump.

Not the real Donald Trump. In a play on It’s a Wonderful Life, “It’s a Wonderful Leap—May 10, 1958” saw Beckett playing a New York City taxi driver. An angel shows up, but that’s not the real kicker of this episode: at one point, Beckett picks up a boy and his father and begins talking to the kid about real estate and what life will be like in the future, and makes specific mention of the glass tower being constructed next to Tiffany’s. In essence, giving Young The Donald the idea for Trump Tower.

7. Jennifer Aniston appeared in an episode.

Two years before Friends debuted and turned Jennifer Aniston into a household name, she starred in the season 5 episode “Nowhere to Run – August 10, 1968,” playing a volunteer at a hospital that aids Vietnam veterans. In the episode, Beckett leaps into the body of a soldier who has lost his legs. Aniston doesn’t have just a cameo, either—she’s in most of the episode.

Besides Aniston, several other future stars appeared on the show, including Joseph Gordon-Levitt in 1991, and Neil Patrick Harris, who was already making waves on Doogie Howser, M.D.

8. The show received pushback for an episode involving a gay character.

One of the best things about Quantum Leap was how it tackled social issues, though that didn’t always sit well with viewers. In the 1992 episode “Running for Honor—June 11, 1964,” Beckett visits a naval college to prevent homophobic classmates from killing a gay cadet. NBC reportedly lost about $500,000 on the episode, because many sponsors pulled out of advertising before it aired. In an earlier shooting script, the gay cadet committed suicide, but that was softened for the final version.

The network didn’t want to cause a fuss over the episode, so they marketed it as “Sam’s life hangs in the balance when he’s accused of betraying his country” and eschewed mentioning the gay plotline. Before it aired, the writer of the episode, Robert Harris Duncan, received criticism from the Los Angeles chapter of the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD). “I’m upset with [the alliance] because I think the script does not slur gays,” Duncan, who was openly gay, told the Chicago Tribune. “I have the opportunity of getting on prime-time television a story on gay bashing and outing. My own group of people is slamming my script down.”

9. The series finale polarized fans.

Because NBC hadn’t told Quantum Leap’s producers whether they planned on renewing the show for another season, Bellisario had to wrap up the last episode of season five the best way he could, and write it as if they weren’t coming back. “Mirror Image—August 8, 1953” ended with Beckett deciding to keep leaping and not return home. Some fans felt the episode didn’t give a proper resolution to the show, but Bakula liked the ending.

“[Bellisario] left doors open. He wrapped some things up, he made people feel good, there was a ton of emotion in it—it was just a metaphor for the show that continues and lives on to this day,” Bakula told Zap2It. “I think it’s a beautiful ending. It was challenging, it was difficult, but I think it was the only answer. I like it. I like that Sam’s out there, and I like that Al got to make his life right.”

10. Donald Bellisario recreated his dad's bar for the show's final epiosde.

Al’s Bar in the series finale is actually a recreation of Bellisario’s father’s bar from 1953. “I created Quantum Leap, my dad created me, so I made it in my dad’s bar,” Bellisario told Emmy TV Legends. “We recreated that bar to every detail that I could remember or find in photographs. I even had the taps from the bar and we used those. The ice cream cooler was the same; the back bar was the same. I did it as an homage to my dad and I did it because I wanted to sit there and be back there.”

11. Fans turned Sam Beckett's name into an acronym.

Akin to “What Would Jesus Do?” (WWJD), Sam Beckett’s choices influenced his fans. “I had a funny thing happen in San Diego last year,” Bakula told Chicagoist in 2012. “This guy told me how he used to watch Quantum Leap with his mom, and as he was growing up, he would call her, and if he was having a tough time with something, he said she would use an expression that always made him feel better: WWSBD. I looked at him and I was like, ‘What is that?’ And he said, ‘What Would Sam Beckett Do?’ And he meant it very sincerely, and I thought that was so very sweet. That moment really stands out to me.”

12. Quantum Leap was novelized.

From 1992 to 2000, Berkley published the show in book form—18 novels in total. Universal asked Berkley to hire writers, like Ashley McConnell, to write whatever they wanted. “When Universal saw the synopsis, the only feedback I got was, ‘Make sure Sam and Al interact,’” McConnell told Starlog. “I never got anything else. They’ve given me all the rein in the world.” Her book, The Novel, was the first in the line of books, which entailed historical stories of the Berlin Wall and Sam leaping into the body of a priest.

13. The show was also turned into a comic book series.

Akin to the novelization of the show, Quantum Leap stories also graced the pages in several graphic novels. Innovation Publishing obtained the rights from Universal and used different writers per issue. In 1991, the first comic was published. Throughout the 13 issues that were published between September 1991 and August 1993, Beckett visited the Stonewall riots, tackled the 1950s quiz show scandal, and, in Freedom of the Press, leaped into the body of a man who’s about to be executed—just like in the episode “Last Dance Before an Execution—May 12, 1971,” which aired a few months before the comic book was released.

14. There have been rumblings of a reboot.

The creators and stars of the show constantly get asked if the show will ever be rebooted. In 2002, the Sci-Fi Channel (before it was changed to Syfy) stated that they planned on developing a two-hour Quantum Leap TV movie, but that never came to fruition. Eight years later, at Comic-Con in 2010, Bakula said that Bellisario was working on a script for a possible Quantum Leap movie. And in 2017, Bellisario said that the script had been completed:

"I write things exactly the same way. I just start writing and I let them take me wherever it’s going to take me. I’m entertained the same way the audience is. So I just put Scott [Bakula] and Dean [Stockwell] in my head, kind of rebooted them, and went from there."

As for whether a reboot will ever happen: stay tuned.

15. Bakula knows what he'd do if Quantum Leap were real.

Even today, Bakula is regularly asked what he would do if he were really able to leap back to any point in history. “I wish, certainly, I could go back and change the course of any of the World Wars that have caused so many losses,” he said in an interview with The Reel Word. “And of course, more recently when we think about 9/11 or things like that, if we could have had knowledge to stop some of those things, you’d want to do that. You know, it would be fun to go back to the days of yore and the courts of such and such, but I always tend to think more about the huge world events that have happened and if there was some way we could have prevented these big disasters.”

The original version of this article ran in 2016.