by David McCullough is a master class in how little most of us really know about Orville and Wilbur Wright, two men of humble origins who would give humanity the impossible gift of flight. Theirs was more than a singular good idea executed at the right time. The Wright Flyer was less the work of two aeronautic savants than it was the result of tireless and obsessive labor and study by two men whose full-time careers were running a bicycle shop. To invent the airplane, they had to invent inventing; no reliable mathematics tables existed for scaling wings to carry humans, and much to their surprise and dismay, no usable research existed at all on the workings of this thing called a propeller.

The magnitude of the problem was (and remains) virtually inconceivable: how to build the wings; how to control a flight; where to position a person on this contraption; how to launch it; how to land it; how to build it; and how to build a suitable motor to run the thing. They had to deal with such problems while facing mockery by science journals of note, which dismissed the idea of human flight as the lunatic notions of suicidal cranks. To overcome the challenges intrinsic to changing the world, the Wright Brothers, as McCullough's masterful biography describes, depended on another person, largely unheralded, who played a vital role in the creation of the airplane: their sister, Katharine.

THE TEACHER OF "THE SAWED-OFF VARIETY"

Katharine Wright was the youngest of five and the only of her siblings to graduate from college. After finishing Oberlin, she took a job teaching Latin at Steele High School, where "she would flunk many of Dayton's future leaders." Brilliant, sociable, and vivacious, she provided an unshakable foundation of support for her brothers in all their endeavors: the print shop they co-founded, then the bicycle shop they started, and finally their interests in flight. Though she did not design, build, or pilot the famed Flyer, she played a vital role in its creation and later popularization.

Katharine was the sounding board for her brothers. While Orville and Wilbur tested their prototype flying rigs at Kitty Hawk, a desolate North Carolina village chosen for its windy skies and sandy beaches (perfect for landing), they corresponded extensively with Katharine. They explained their successes and setbacks, and after particularly tough trials which left them certain that their idea was a hopeless one—that the journals were correct about human flight being impossible—Katharine offered support, encouragement, and advice. Her contributions to the initial tests at Kitty Hawk were both big and small. She packed food for the brothers to enjoy in their initial austere environs. Through humorous correspondence, she gave them an outlet to share and consider problems outside of engineering and physics.

More substantially, during school holidays, while her brothers were at Kitty Hawk and beyond, she kept the Wright Cycle Company solvent, firing incompetent managers and helping in its day-to-day operations. The Wrights were privately funded. Their bicycle shop was crucial to their work, and provided every penny they spent in the development of the airplane. They wanted no government assistance and no outside investors.

When word later spread of the brothers' modest successes, engineering societies requested public talks—something the Wright Brothers were hardly prepared for or eager to attempt. It was Katharine who pressed them to attend such events, and even chose the clothes they should wear. The most notable of these speeches—"Some Aeronautical Experiments," delivered by Wilbur—would later be described as the "Book of Genesis of the 20-century Bible of Aeronautical Experiments." It wouldn't have been given without Katharine's insistence.

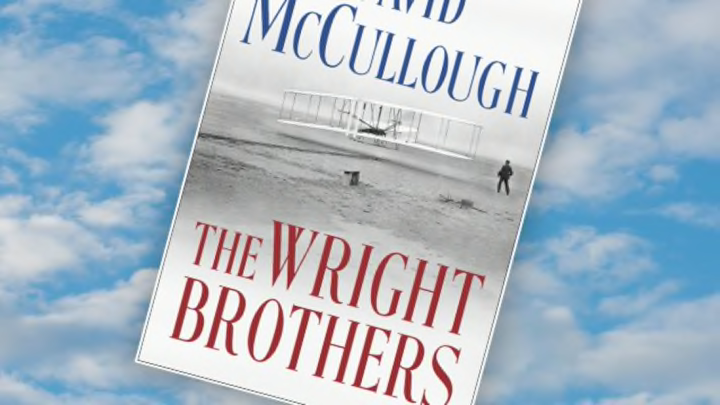

Public Domain // Wikimedia Commons

The Wrights were a close family. Orville and Wilbur never married, and Katharine married in 1926, three years before her death. (Wilbur had died 14 years earlier of typhoid fever.) Because of the family's closeness, the health of their beloved father was always a concern. In addition to tending to the bicycle shop, Katharine cared for their father, freeing her brothers to continue their work without guilt or anxiety.

THE BURDEN OF PROOF

For Wilbur and Orville, achieving the impossible and actually building a working airplane wasn't enough. The Wrights faced the challenge of showing people that their airplane actually existed. People simply didn't believe it. Long after the Wright Flyer was zipping through the skies of Ohio, Scientific American ran a skeptical and dismissive piece titled "The Wright Aeroplane and Its Fabled Performances." Witness accounts were roundly ignored, and photographs were asserted to have been forgeries.

The Wrights were undaunted by this. They wrote the War Department and explained what they had created, providing photos of their invention. Their correspondence was ignored. The French government approached the Wrights, however, and expressed great interest. The brothers had to box up their creation and ship it overseas, guarding it jealously throughout—once details of the design breakthroughs of their plane leaked, their invention would be rendered valueless.

Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons

Public demonstrations in Paris proved sensational. Far beyond attracting the interest of military officials, they captured the imagination of the entire country, and soon, the entire continent. Hundreds of thousands of people showed for public demonstrations, and the Wrights were feted in every corner. This was more troubling than one might think. The Flyer worked marvelously, but it wasn't idiot-proof; on every flight, one wrong move would mean catastrophe for the pilot. Parties at palaces hardly left time for the serious business of pilot preparation. Wilbur, who ran the Europe operation, needed someone to handle the social aspects of the job.

Back in the United States, Orville ran the demonstration flights for the now-very-interested U.S. government. When he suffered a devastating and nearly fatal crash in Washington, however, it fell to Katharine to help him when doctors had all but written him off. As McCullough writes, "There was never a question of what she must do. Moving into action without pause, she called the school principal [where she worked], told her what had happened, and said she would be taking an indefinite leave of absence. Then, quickly as possible, she packed what clothes she thought she would need and was on board the last train to Washington at 10 that same evening." She would devote herself to the rehabilitation of her brother.

The terrible nature of Orville's injury and his recovery took its toll on her. She later wrote to Wilbur, "Brother has been suffering so much … and I am so dead tired when morning comes that I can't hold a pen." Orville would later say that without his sister, he would not have survived.

CELEBRITY

Eventually, the furor in Paris became too much, and Wilbur beseeched his sister to come to Europe and act as his "social manager." She agreed, bringing Orville with her. In addition to caring for the greatly weakened brother while in Europe, she took public pressure off of Wilbur by wining and dining the world's aristocracy, who simply could not get their fill of the astonishing Wright Brothers and their miracle of human flight. She entertained kings, prime ministers, and business titans alike. She took French classes two hours every morning. Because she was fluent in Greek and Latin, she picked up the language quickly, and with a native speaker on their roster, the Wrights were able to cause an even greater splash in Parisian society. According to McCullough:

"The less Orville had to say, the more Katharine talked and with great effect. She had become a celebrity in her own right. The press loved her. 'The masters of the aeroplane, these two clever and intrepid Daytonians, who have moved about Europe under the spotlight of extraordinary publicity, have had a silent partner,' wrote one account. But silent she was no longer and reporters delighted in her extroverted, totally unaffected Midwestern American manner."

One account of Katharine put it most succinctly: "Who was it who gave them new hope, when they began to think the problem [of flight] impossible? … Who was it that nursed Orville back to strength and health when the physicians had practically given him up after that fatal accident last September?"

During all of this, Katharine maintained correspondence with their father back home—freeing desperately needed time for the Wright Brothers to maintain their plane and the bearing necessary to fly it. Moreover, when the Wrights needed to take someone up as a passenger, they often took Katharine, if only to demonstrate their confidence in the flying machine. Katharine had flown "longer and farther than had any American woman." She was, in fact, the "only woman in the world who had made three flights in an aeroplane," and she would become, at the time, the only woman ever invited to a dinner at the Aéro-Club de France.

She was an ambassador of sorts for America in Europe, and later, for Europe in America. She took the American press to task for diminishing the European fascination with flight. "She loved America, she said, but the American people did not always understand Europeans, who were an appreciative people. She could not listen to anyone saying unkind things about them without protesting."

All of this set the stage for her later life. She was a visible member of the suffrage movement. She traveled the world and devoted her time to Oberlin College. After the death of Wilbur, she supported Orville's successful business ventures to the last.

Katharine, the Wright Sister, died in 1929.